The film star and humanitarian talks about training women to care for bees in UNESCO biosphere reserves…and about the bee that got under her dress.

It’s startling at first glance to see an iconic beauty’s face and body swarmed by bees. A closer look tells a deeper story of the delicate balance between humans and the pollinating insects we depend on for so much of the food we consume.

In 2021, Angelina Jolie posed for a striking portrait for National Geographic to draw attention on World Bee Day to the urgent need to protect bees—and to a UNESCO-Guerlain program that trains women as beekeeper-entrepreneurs and protectors of native bee habitats around the world. Photographer Dan Winters, an amateur beekeeper, drew his inspiration from a famous 1981 Richard Avedon portrait of a bald California beekeeper, whose naked torso was covered in bees.

Jolie was inspired by different visions: of bees as an indispensable pillar of our food supply—one that’s under threat from parasites, pesticides, habitat loss, and climate change—and of a global network of women who will be trained to protect these essential pollinators.

The actor, director, and humanitarian activist joined me for an interview in Los Angeles to talk about the connections among a healthy environment, food security, and women’s empowerment, and the estimated 20,000 species of bees, including 4,000 native to the United States. Protecting life-sustaining pollinators is a challenge well within our grasp, she said.

“With so much we are worried about around the world and so many people feeling overwhelmed with bad news,” Jolie said, “this is one [problem] that we can manage.”

A scanning electron micograph of a worker bee.

The head of a queen bee. PHOTOGRAPHS BY DAN WINTERS

Three out of every four leading food crops for human consumption—and more than a third of agricultural land worldwide—depend in part on pollinators, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization. It’s not just fruits, nuts, and vegetables; bees also pollinate alfalfa consumed by cows and crops used for clothing and medicines. Honeybees alone enable an estimated $20 billion in U.S. crop production, according to the American Beekeeping Federation; pollinators support well over $200 billion in food production worldwide.

Yet bee populations in several nations suffered severe declines in the decade after colony collapse disorder was identified in 2006. (Read about how billions of dollars ride on saving pollinators.) Those mass bee die-offs have been linked to pesticides (especially a group of chemicals called neonicotinoids), parasitic varroa mites, and shrinking native habitat exacerbated by large-scale commercial monoculture. Climate change has also disrupted native species around the world, landing more than half a dozen native U.S. bee species on the Endangered Species List. (Read about bumblebees going extinct in a time of ‘climate chaos.’)

Jolie was recently named “godmother” for Women for Bees, a five-year program launched by UNESCO, the UN’s educational, scientific, and cultural arm, and Guerlain, the French cosmetics house. Guerlain says it has contributed $2 million to train and support 50 women beekeeper-entrepreneurs in 25 UNESCO-designated biosphere reserves around the world.

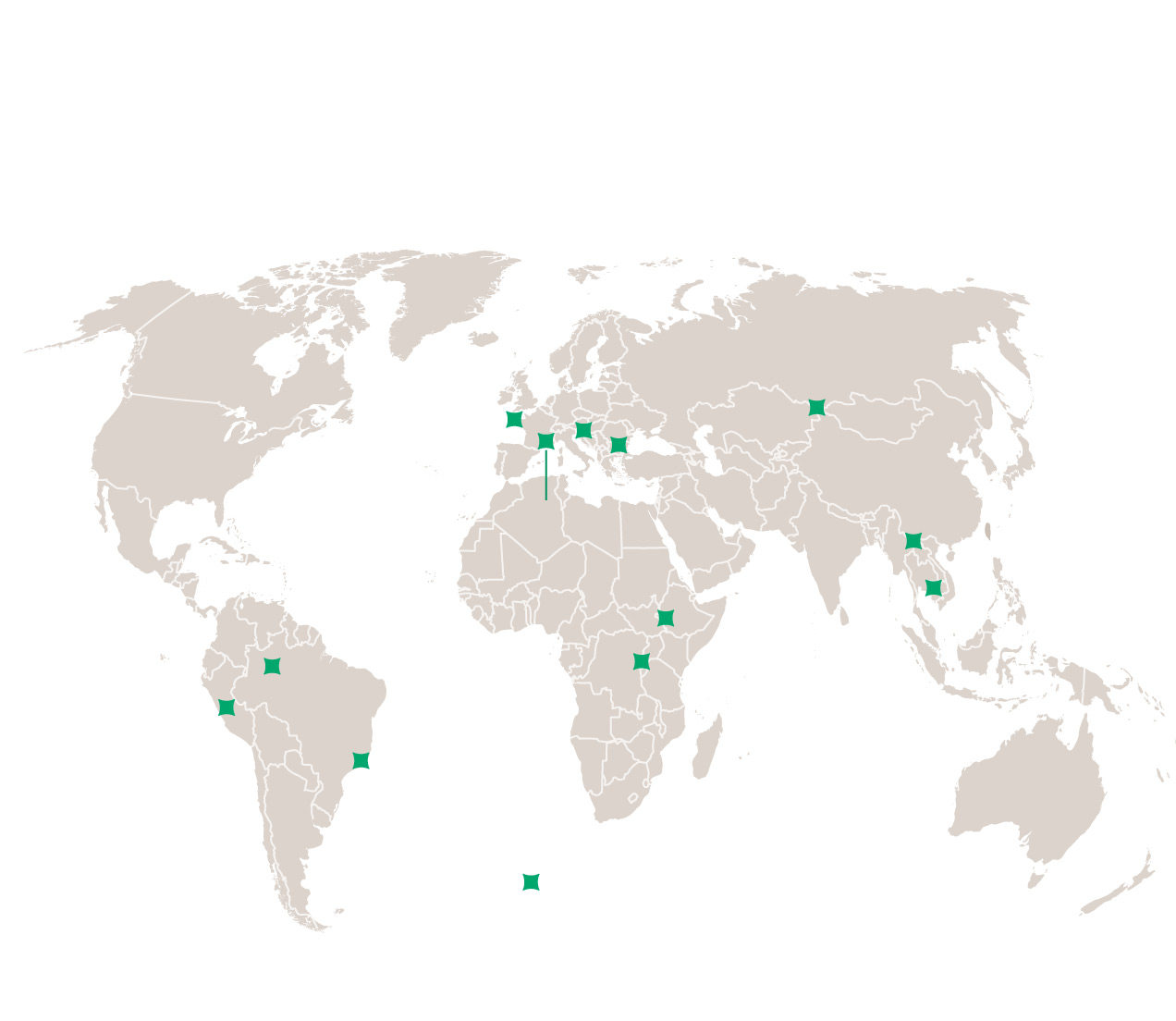

The women are expected to build 2,500 native beehives by 2025, safeguarding 125 million bees, according to Guerlain. Women from Bulgaria, Cambodia, China, Ethiopia, France, Russia, Rwanda, and Slovenia will be trained this year, with others from Peru, Indonesia, and more joining in 2022.

A key objective of the program is to highlight the diversity of local beekeeping practices, sharing the know-how of different cultures. In the Xishuangbanna Biosphere Reserve in China, for example, locals use log hives made of fallen trees sealed with cow dung to protect bees in winter. In the Tonle Sap Biosphere Reserve in Cambodia, beekeepers raise colonies on inclined branches that make it easy to harvest honey without destroying a colony. UNESCO officials told me that under the Women for Bees program, neither colonies nor queens would be imported, to avoid driving out native bees or spreading disease.

Bees in the Biospheres

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization designates certain protected areas as biosphere reserves. These places work to reconcile conservation with sustainable human use. A new pilot program in several reserves is working to train women as beekeepers.

Jolie comes to her new role with unusual experience. A special envoy to the United Nations’ High Commission for Refugees, she has participated in nearly 60 UN missions to warzones and refugee camps in the last 20 years. In 2003 she started a conservation and community development foundation, named for her eldest child, Maddox, in a protected region in rural, northwestern Cambodia. The foundation has worked to remove wartime landmines, retrain wildlife poachers as forest rangers, and promote gender equality, among other goals. It also trains beekeepers.

In June, Jolie will join the first 10 Women for Bees to take part in an accelerated 30-day training led by experts at the French Observatory of Apidology in Provence, where she plans to get trained in beekeeping as well.