THE Queen was in her mid-50s and the succession was not assured.

Son and heir Prince Charles had said that, “Thirty seemed a good age to get married”.

5

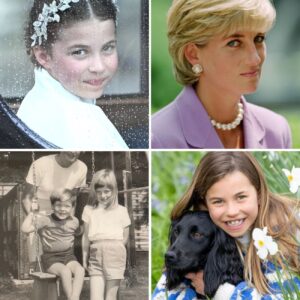

Diana, in a maternity dress, reacts during a chat at a polo match, Windsor, May 1982 Credit: Getty

5

The Queen and Diana fuss over bridesmaid Clementine Hambro, Churchill’s great-granddaughter, on the wedding day, July 29, 1981 Credit: Patrick Lichfield – Getty

5

The Queen and Diana on Buckingham Palace balcony after the wedding. More than 750million watched on TV worldwide Credit: Getty

But he was approaching 32. And despite a series of high-profile girlfriends there was no sign of him settling down and producing an heir.

His mother knew from history — including the painful personal history of her uncle’s abdication — that the monarchy slipped into crisis when succession was an issue.

She also knew — because a courtier had felt obliged to tell her — of her son’s affair with Army officer’s wife Camilla Parker Bowles.

Charles had been besotted by Camilla since they dated in the early 1970s. But everyone was against “the prospectless liaison”.

The prince had recently become friendly with Lady Diana Spencer, an 18-year-old whose father Earl “Johnny” Spencer had been equerry to the Queen and George VI.

Diana and Charles had first met when she was 16 as he dated her sister Sarah. And the Queen’s desire for Charles to put Camilla behind him encouraged hopes that their friendship would lead to marriage.

The result, according to historian Ben Pimlott, was a “fateful collusion” which drew Diana and the prince “into a marriage of convenience that was disguised to everybody, including themselves, as a love match”.

Pimlott added: “The Queen played a part in the collusion.”

In summer 1980, The Sun’s royal photographer Arthur Edwards took the first Press photo of Diana as she watched the prince play polo.

A couple of months later, the Queen invited Diana to Balmoral. Driving beside the River Dee, Arthur spotted Lady Diana as she watched Charles fish for salmon.

“I spoke to my contact,” recalls the photographer, “who said, ‘She’s following him around like a lamb’.

“It was not a question of if Charles was going to marry her but when.”

And in September 1980, after Arthur took his famous photo of Diana with the sun shining through her skirt at the London nursery where she then worked, the world was gripped with Lady Di mania.

At Sandringham that Christmas even the normally unflappable Queen snapped, telling photographers hoping for a picture of Diana: “Why don’t you go away?”

Soon after, on February 6, 1981 — the 29th anniversary of the Queen’s accession to the throne — Charles proposed to Di at Windsor Castle.

She immediately accepted — and Charles rang his mother. Charles and Diana had met just 13 times.

“Both treated the engagement like a prize,” writes Pimlott. “To be displayed as quickly as possible in case anyone had second thoughts.”

The engagement was announced on February 24. In a TV interview, when the couple were asked if they were in love, Diana instantly answered, “Of course”. But Charles added the fateful words: “Whatever ‘in love’ means.”

Diana later said his answer, “absolutely traumatised me”.

A month later, the Queen gave her formal approval to the marriage at a meeting of the Privy Council. Later, Diana and Charles posed with her in Buckingham Palace’s Music Room for an official photograph.

Her Majesty could not have been more pleased. Diana was a safe choice and, most importantly, “one of us”. But for Diana, the pressure of the impending July 29 service at St Paul’s Cathedral made her physically sick. “I felt like a lamb to the slaughter,” she said.

In the months before the big day, her problems with bulimia began.

She had moved into Buckingham Palace to escape the media, but felt cut off from her friends and desperately lonely. The Queen’s overtures of friendship only caused more stress.

Her Majesty, unaware of Diana’s problems, would invite her to lunch to get to know her.

But Diana, still a teenager, would tell her friends: “I don’t know what to say to the Queen.”

The two women had nothing in common and nothing to talk about. And the Queen soon came to think that Diana was “highly strung” — but she was confident she knew how to handle her. She would say: “I treat her like a nervy racehorse.”

Meanwhile, the Queen threw herself into the wedding fever that consumed the nation. She even rang the Archbishop of Canterbury to chat about the music for the service.

The wedding itself was spectacular, with three quarters of a billion people tuning in across the world. Some 600,000 lined the streets to cheer the newlyweds in their open-topped carriage back to Buckingham Palace.

There, the Queen, wearing light blue, looked on as the couple kissed on the balcony — a move that would become a royal wedding tradition.

Charles, 32, and Diana, 20 earlier that month, began their honeymoon at Broadlands, the Hampshire family estate of the Mountbattens where the Queen and Prince Philip had honeymooned in 1947.

Then, after an 11-day Mediterranean cruise, the couple flew to Balmoral where they posed happily for photographers. But the marriage was already under terrible strain.

During the cruise, Diana was horrified to see photos of Camilla fall out of Charles’s diary. Then she found him wearing cufflinks from Camilla, engraved with their initials.

By the time they got to Balmoral to join the other royals, Diana was miserable. But when she turned up late for meals, or left them early without explanation, the Queen and Prince Philip ignored her behaviour.

Friends of Charles later claimed he blamed his parents for not being more supportive of his young bride.

One revealed: “He felt very let down by his unsympathetic mother and father. When his marriage went wrong he felt criticised by them.”

But a courtier of that period said: “The Queen was aware of the stresses and strains. She was wholly sympathetic towards Charles, in fact rather one-eyed in her approach.”

Despite the birth of an heir, Prince William in 1982, and of Prince Harry two years later, by the mid-1980s Charles and Diana were effectively living separate lives.

Diana tried to seek comfort from the Queen, but the monarch just could not work out a way to give her what she needed. The princess would burst into her mother-in-law’s sitting room in floods of tears, often shouting: “Everyone hates me!”

The Queen could not deal with it. Nothing in her life had prepared her for that kind of emotional display.

Philip was different, writing long letters to Diana, trying in vain to bring her back into the fold.

The full extent of the anguish did not emerge until 1992 and the Andrew Morton book Diana, Her True Story.

In it, Diana attacked the Royal Family, but stopped short of criticising the Queen, saying she had a “deep respect” for her work.

Diana had promised her mother-in-law: “I will never let you down.” Months later, in December 1992, PM John Major stood in the House of Commons to announce Charles and Diana’s “amicable separation”.

The Queen still hoped they might repair the marriage. But in the years that followed, Charles and Diana went on TV and admitted adultery. First it was Charles, in an interview with Jonathan Dimbleby on ITV in 1994, which caused a massive surge in sympathy for Diana. By May 1995 the princess’s soaring popularity was such that the Queen feared being booed on the Buckingham Palace balcony at the 50th anniversary of VE Day.

Diana’s interview with Panorama in November 1995 won her even more sympathy when she said: “Well, there were three of us in this marriage, so it was a bit crowded.”

And she added: “I’d like to be a queen of people’s hearts.” Princess Margaret, one of Diana’s biggest supporters — who could no doubt see elements of herself in her young relative — regarded this as an attack on the Queen and turned against the princess.

Tony Blair, whose New Labour project was courted by Diana before and after he became PM in 1997, said in his 2010 autobiography that the princess’s influence was, “gravely disconcerting for the monarchy as an institution” — and hence the Queen.

He wrote that her contrast with the royals, “illuminated how little they had changed”, and, “for someone as acutely perceptive about the monarchy as the Queen, it must have been deeply troubling . . . suddenly an unpredictable meteor had come into this predictable and highly regulated ecosystem”.

A month after the Panorama interview, the Queen wrote to Charles and Diana advising them to divorce. As mother to a future king, Diana would still be considered a member of the Royal Family, but during wrangling over the split she announced she was giving up the title Her Royal Highness.

Diana changed her mind about the title and called the Queen, but she replied the matter was “very difficult” — her way of saying no. She later remarked: “She wanted to give up the title, so give it up she will.”

One of the Queen’s closest friends, Lady Kennard, said: “I was always surprised that they didn’t get on. The Queen wouldn’t have a row with anyone. But she was rather surprised by many things. I think the Queen would never quite understand what Princess Diana was about.”

On August 28, 1996, Charles and Diana’s divorce became final. A year and three days later, the princess was killed in a car crash in Paris — a tragedy that presented the Queen with one of her deepest crises.

5

A photocall after the Queen formally approved the marriage, March 1981 Credit: Getty

5

Diana gives her mother-in-law a kiss on the cheek in 1981 Credit: Getty