I must have missed when Tyson fought Lesnar… – When Mike Tyson Loses Control in His Main Boxing Confrontation

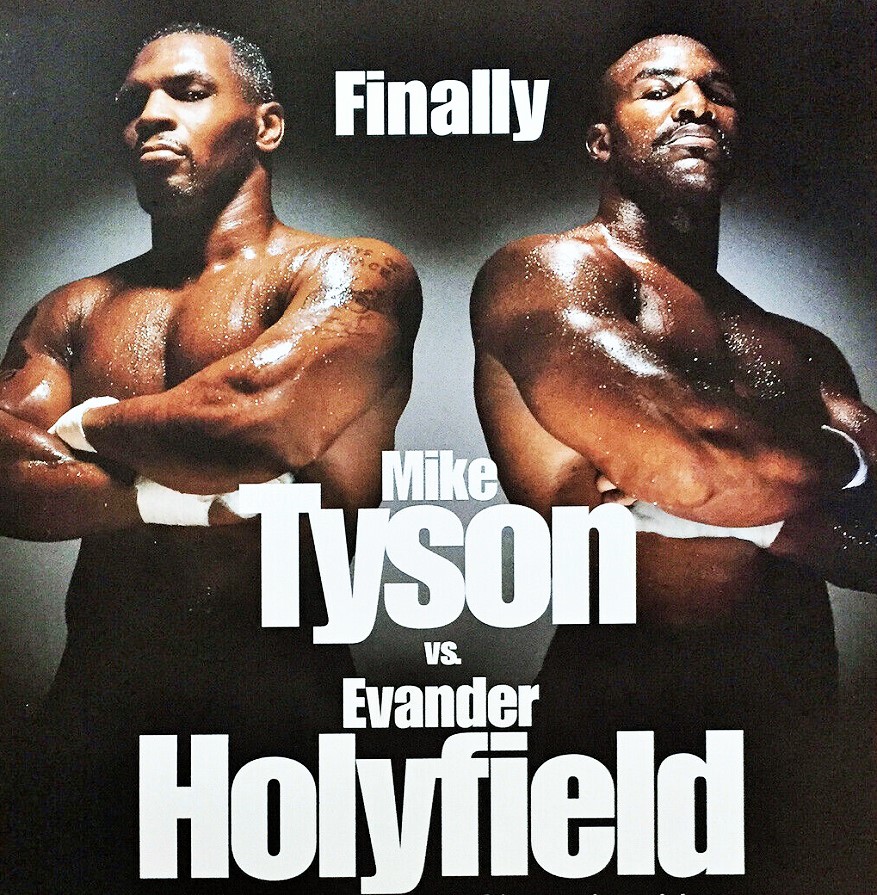

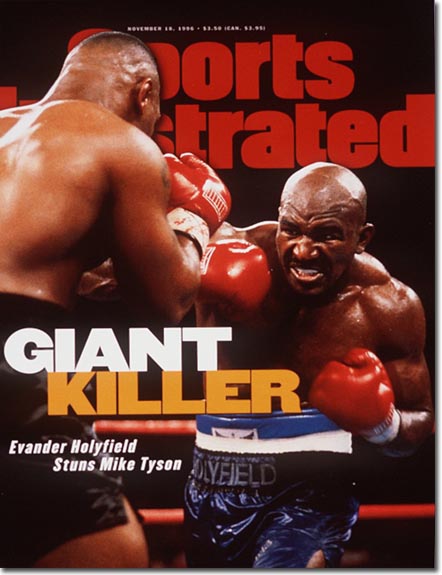

In the first fight, which took place at the end of 1996, Holyfield created a sensation. He entered the fight as an outsider at 5:1, but went on to control most of the fight, and..

Intimidation. From the jungles of our primitive ancestors, to the boardrooms of today’s suit-and-tie warriors, the ability to demoralize an antagonist without resorting to physical violence remains a key weapon in the struggle for dominance. Arguably no boxer understood this better, or implemented fear tactics more effectively, than Mike Tyson. Even when the former “Kid Dynamite” had lost much of his talent to time, self-indulgence, thuggish sycophants and Don King, he could still freeze an opponent’s heart with little more than a menacing glare.

To understand this aspect of Tyson’s ring persona, it’s helpful to recall that he was forged by the meanest streets of Brooklyn, New York, arrested thirty-eight times before he was even 14-years-old. The law of the jungle, kill or be killed, was all he knew and he had adapted accordingly. As a boxer, his reputation preceded him and after he turned pro Tyson made intimidation an essential part of his ring success.

It wasn’t just the bulging muscles and those dark, hate-filled eyes; it was the aura of menace that radiated from his every gesture, the sense that the normal laws and restraints of society didn’t apply, that no one could be certain what he might do at any given moment. Tyson’s explosive power and rattlesnake quickness may have been the ostensible factors in his notching 26 stoppage wins in his first 28 bouts, but in fact his most lethal weapon was his unique talent, honed on the streets, for turning an opponent’s knees to water before the bell had even rung. As proof, consider the fact that more than half of Tyson’s career knockouts were secured in the opening round.

Soon after Tyson was released from prison in March of 1995, it was evident that neither his defeat to Buster Douglas back in 1990, nor his time away from the ring, had done anything to erode this ability. His first comeback match ended after 89 seconds when Peter McNeeley’s trainer, fearing for his fighter’s life, signaled surrender. Frank Bruno appeared the very definition of abject terror when he faced Tyson for the second time, walking to the ring in a manner befitting a condemned man approaching the gallows, twitching and shaking and repeatedly crossing himself. And after dispatching Bruno inside seven minutes, the next lamb to the slaughter, Bruce Seldon, presented an equally graphic image of a man paralyzed by dread when he collapsed to the canvas in the opening round after Tyson in fact missed him with a left hook.

An intimidated Bruno goes down in round three.

None of Iron Mike’s comeback bouts had tested him or offered evidence to support a judgment of his abilities, one way or the other. Despite this, few questioned his reclaimed status as the best heavyweight on the planet, in part because no other fighter had proven capable of domination. Riddick Bowe had looked terrible against Andrew Golota, while Lennox Lewis had yet to regain his high standing after his stoppage loss to Oliver McCall. Most could not see past Tyson’s fearsome image, still his most deadly weapon, to the fact that several contenders, including Lewis and Ray Mercer, deserved to be ranked higher. As far as the public was concerned, “Iron Mike” was back, a phenomenon once again, as dangerous as ever.

So who can blame the Vegas bookies who initially judged Evander Holyfield a 25-to-1 underdog when Tyson’s next victim was announced? The champion was the baddest man on the planet, while Holyfield was clearly done like dinner. At the time most decried Holyfield vs Tyson as a pitiful mismatch and many feared for Evander’s safety. In his last several bouts “The Real Deal” had looked washed up, at times even enfeebled, and he had absorbed so much punishment in so many wars that the consensus was he had to be completely shot. So concerned was the Nevada State Athletic Commission for Holyfield’s welfare, not to mention their own liability, that they ordered a full battery of medical tests before allowing him to enter the ring.

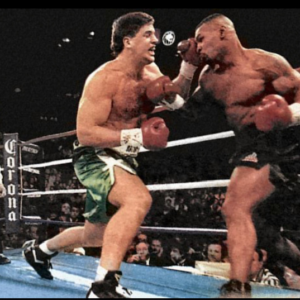

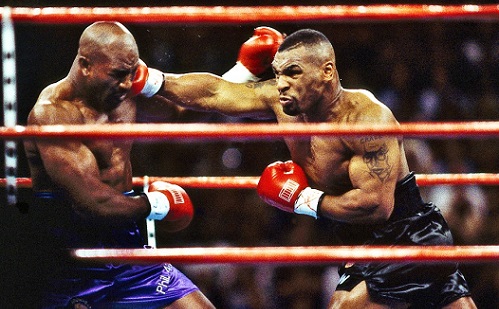

Tyson charges Holyfield at the opening bell.

A capacity crowd assembled at the MGM Grand to witness the expected execution. Here came the next knockout; the only question was how dramatic and violent it would be. When the bell rang and Tyson landed a right hand that sent Holyfield skittering across the ring, it looked like the fight might be over in the opening minute. But then a strange sight presented itself: Tyson’s appointed victim did not cave in and crumble and in fact, did not appear to be the least bit intimidated. Instead, to everyone’s shock, he was fighting back, scoring with quick left hooks to the body as Tyson bulled forward, and then hard right hands upstairs. This was the last thing anyone expected, including the defending champion.

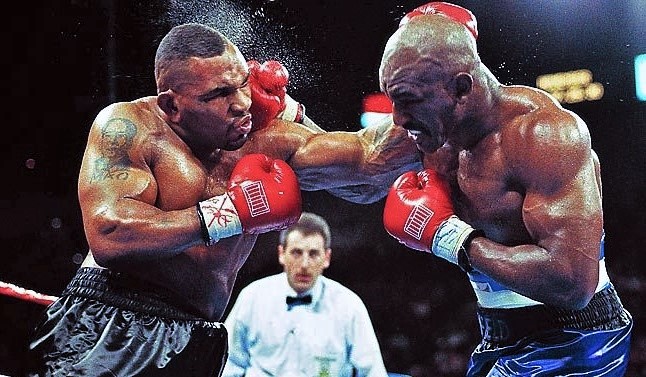

In round two Holyfield did what no opponent had done to Tyson since his loss to Douglas almost seven years earlier: force him to the ropes and hit him with flush shots, including a powerful left that snapped Mike’s head back. And at that moment, the outcome was decided; Tyson did not know how to deal with an opponent who refused to follow the familiar script. By contrast, Holyfield’s confidence only grew as he continued to exploit his advantages in height, reach and physical strength, while mixing in a few head butts for good measure.

Evander takes control.

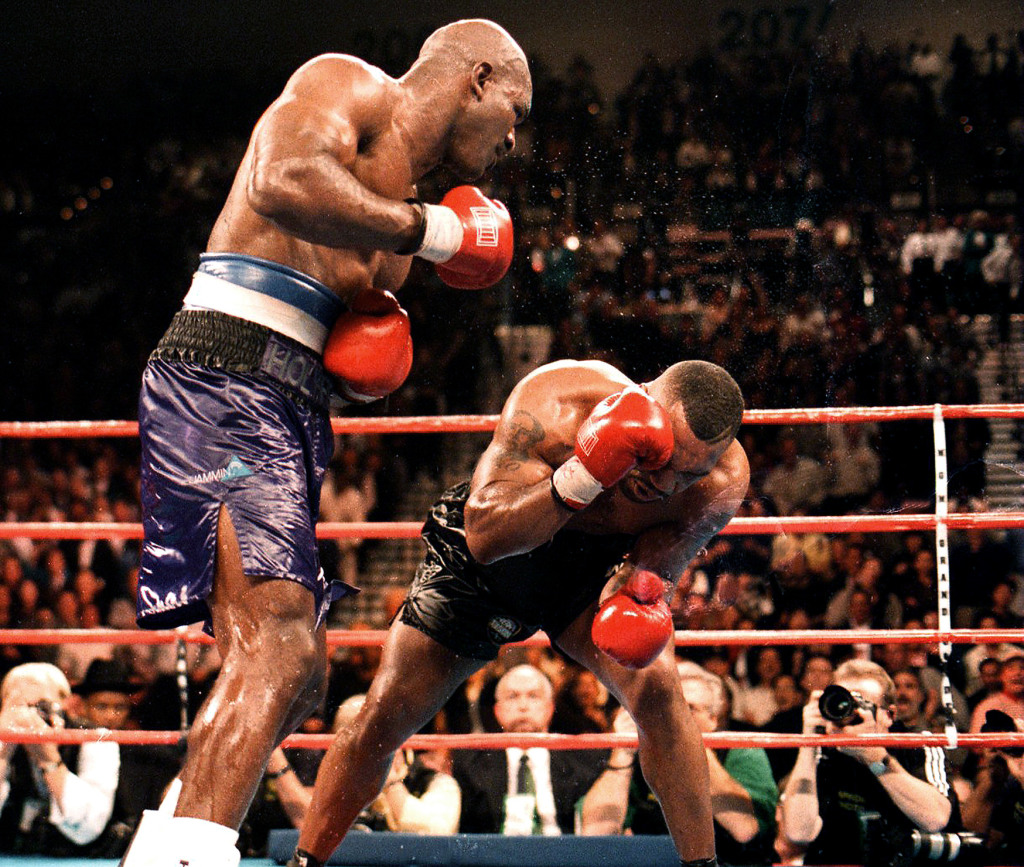

But Evander had already established the dominant pattern of the fight: pushing Tyson back in the many clinches, bullying the bully, and immediately countering with hard shots on the rare occasions the champion launched an effective attack. In the sixth Tyson sustained a cut, was stunned by a right hand, and then suffered a knockdown. The rest of the bout fascinates primarily in regards to the visible dissolution of Tyson’s confidence, his bully persona crumbling to reveal the yawning vacuum beneath.

A hard right hand in round ten was the beginning of the end.

In the tenth the inevitable happened. Tyson had already been stung several times over the course of the battle, but with twenty seconds left in the round Holyfield inflicted truly serious damage with a perfectly placed counter right to the temple and the crowd instantly came to its feet as Tyson’s legs buckled. Instead of forcing a clinch, the dazed champion unwisely kept trading shots and the result was another huge right that sent him stumbling across the ring; only the ropes prevented a knockdown. Holyfield got home eight more clean punches before the bell and as the champion walked unsteadily back to his corner it was abundantly clear the fight was over. A still-hurting Tyson answered the bell for the eleventh but Holyfield quickly finished him off, the referee stopping the contest with Mike defenseless on the ropes.

Tyson struggles to stay on his feet.

Looking back, it’s curious that, even after this one-sided shellacking, Tyson’s image did not suffer irreparable damage, that many still regarded him as an incredibly dangerous fighter. He was actually a slight betting favorite going into the inevitable rematch with Holyfield, which ended after Tyson bit both of Evander’s ears.

But again, like his rape conviction, this outcome only reinforced Tyson’s persona as a fearless and menacing thug, an image which he further cultivated when he tried to break Frans Botha’s arm in a clinch, punched a defenseless Orlin Norris after the bell, and struck a referee as he tried to pummel Lou Savarese after the bout had already been stopped. Outside the ring, Tyson was involved in various altercations, and even served another prison sentence in 1999. While the truth was that he had little to offer anymore as a boxer, “Iron Mike’s” menacing image allowed him to collect one more huge payday when Lennox Lewis battered him in 2002.

But it was his first clash with Evander Holyfield which should have ended his marketability as a boxer. Holyfield, like Buster Douglas before him, had refused to be intimidated and thus had revealed the truth: Tyson had devolved into a one-dimensional brawler with precious few resources beyond raw power and a unique talent for striking fear in an opponent’s heart. The irony of this historic fight is that the boxer everyone thought finished, was not, and would go on to compete at the highest level for several more years, while the man everyone viewed as unstoppable, was in fact little more than a hollow shell of a once truly fearsome pugilist. — Michael Carbert