On June 6, 1944, General Omar Bradley stood aboard the cruiser Augusta 12 miles off the coast of Normandy and faced a decision that could lose the war. Reports from Omaha Beach were catastrophic. Entire companies had been wiped out in the first minutes. Bodies floated in the surf.

Survivors huddled behind a seaw wall while German machine guns cut down anyone who moved. Bradley began drafting contingency orders to evacuate the beach head and divert all follow-up forces to Utah Beach or the British sectors. The greatest amphibious invasion in human history was dying on the sand. Seven miles closer to shore, a 34year-old naval officer named Robert Beer stood on the bridge of a destroyer and made a different calculation.

His orders said to stay 5,000 yards offshore, his charts warned of mines, sandbars, and water too shallow for his ship. But through his binoculars, he could see American soldiers dying by the hundreds on a beach that was supposed to be secure by now. Commander Beer turned to his helmsman and ordered flank speed toward the guns.

The invasion planners had promised the army that naval bombardment would neutralize the beach defenses. They were catastrophically wrong. And it would take men like Robert Beer willing to ignore their orders and risk their ships to save the greatest amphibious assault in history from ending in disaster on its very first day. The miscalculation began months before the first landing craft hit the water.

Allied planners faced an impossible puzzle. They needed to land 156,000 men on heavily fortified beaches held by the German army. The operation they designed, cenamed Overlord, would be the largest amphibious assault ever attempted. Success depended on overwhelming the defenders before they could organize effective resistance.

That meant the beach defenses had to be destroyed or suppressed before the infantry reached the sand. The plan called for a massive preliminary bombardment. 480 heavy bombers would carpet the beach positions with 1,300 tons of explosives. Then battleships and cruisers would pound the fortifications with their big guns.

By the time the first soldiers waded ashore, the German bunkers would be rubble and the defenders would be dead or dazed. It was a reasonable theory. It had worked in the Pacific, where American forces had learned to soften up Japanese island defenses with days of sustained bombardment before attempting landings.

At Quadrilene in February 1944, the Navy had delivered two full days of continuous bombardment before the Marines went ashore. At Saipan that same summer, the preliminary fire lasted 3 days. These prolonged bombardments were costly in ammunition and time, but they saved lives by destroying defensive positions before the infantry reached them.

But the European planners made a critical error. They gave themselves only 40 minutes of naval bombardment before the first wave hit Omaha Beach. 40 minutes to destroy fortifications the Germans had spent four years constructing. 40 minutes against concrete bunkers, steel reinforced trenches, and interlocking fields of fire that covered every inch of the beach.

Rear Admiral John Hall, who commanded the naval forces at Omaha Beach, knew this was inadequate. He warned General Bradley that the bombardment plan was insufficient. Hall later said they had attacked Normandy with a shoestring naval force in the most important amphibious assault in the history of the United States.

He called it a crime to send men on the biggest amphibious attack in history with such inadequate naval gunfire support. His concerns were overruled. The planners feared that a longer bombardment would sacrifice surprise and give the Germans time to bring up reserves. The air bombardment failed completely. 480B 24 Liberators approached the coast through heavy cloud cover on the morning of June 6th.

The bombarders could not see their targets through the overcast. Fearing they might hit the approaching landing craft, they delayed their bomb releases by crucial seconds. Every single bomb missed the beach defenses. All 1,300 tons of explosives fell up to three miles inland, killing French civilians and cows, but not a single German soldier in the coastal fortifications.

The massive air raid that was supposed to devastate the beach defenses accomplished nothing. The naval bombardment fared little better. The battleships Texas and Arkansas along with the cruisers Glasgow, George Legs, and Monol opened fire at 550 in the morning. They had 40 minutes to destroy fortifications that the Germans had spent years constructing.

The ships fired from ranges of 10 to 12,000 yds, too far to guarantee accuracy against small concrete bunkers. Smoke and dust from the air raid obscured their targets. The gunners were shooting at map coordinates rather than observed positions. When the ceasefire order came at 6:30 as the first landing craft approached the beach, most of the German positions were intact.

The intelligence failure made everything worse. Allied planners believed Omaha Beach was defended by a single static battalion of about 800 lowquality troops, old men and foreign conscripts who would fold under pressure. The real situation was catastrophically different. In March 1944, nearly 3 months before the invasion, the German 352nd Infantry Division had moved into the coastal defenses.

This was not a garrison unit of old men and foreign conscripts. The 352nd was a combat formation with over 12,000 troops, many of them veterans of the brutal fighting on the Eastern Front. The division had been training specifically for anti-invasion operations. They knew the terrain intimately. They had rehearsed their defensive plans until every soldier understood exactly where to be and what to do when the allies came.

They had strengthened the fortifications with additional bunkers, trenches, and obstacles. When the Americans landed on June 6th, they walked into a defense far more formidable than anything the planners had anticipated. Allied intelligence detected the presence of the 352nd division only on June 4, 2 days before the invasion.

By then, it was too late to change the plans. The assault would proceed as designed with its inadequate bombardment and flawed assumptions against an enemy three to four times stronger than expected. The beach itself was a nightmare of overlapping fields of fire. Omaha stretched nearly six miles along the Normandy coast, a crescent of sand bounded by cliffs at either end.

The Germans had spent four years fortifying this stretch of coastline as part of the Atlantic wall. The defensive system that Hitler ordered built to repel any Allied invasion. They had constructed 15 strong points along the beach, each containing multiple machine gun nests, mortar positions, and artillery pieces.

They called these positions wider stands nest, meaning resistance nest. The strong points were numbered 60-4, stretching from the eastern boundary near Kolivville Surre to the western end near Vil Surre. The fortifications represented the best German military engineering. Concrete bunkers with walls 3 ft thick, housed artillery pieces and machine guns.

The bunkers were positioned not to fire out to sea, but to fire along the beach so that attacking ships would have difficulty hitting them while they rad the sand with enfor. Communication trenches connected the strong points, allowing defenders to shift positions without exposing themselves. Underground ammunition storage and living quarters meant the garrisons could survive prolonged bombardment.

Each strong point was positioned to cover every inch of the beach with interlocking fire. A soldier who escaped the guns of one position would walk directly into the fire zone of another. The Germans had carefully surveyed every yard of sand and registered their weapons to hit precise locations. They knew exactly how far it was from the waterline to the seaw wall.

They knew where men would naturally take cover. They had planned their killing zones with methodical German precision. Behind the strong points, the bluffs rose 100 to 170 ft above the beach. There were only five exits from the sand to the high ground, narrow drawers that channeled any advance into predictable paths. The Germans had fortified these drawers most heavily of all.

Anyone trying to move off the beach would have to pass through a gauntlet of concrete bunkers, barbed wire, and pre-registered artillery fire. The most formidable position was Weeder Stand’s Nest 72, guarding the western exit near Verville. This strong point housed an 88 mm gun in a concrete casemate, positioned to fire directly down the length of the beach.

The 88 was one of the most feared weapons of the war, capable of destroying tanks at 2,000 yards. at Omaha Beach. It could sweep the sand with fire that no infantry assault could survive. The first wave hit the beach at 6:30 in the morning. Within minutes, the assault had become a catastrophe. The soldiers of the first and 29th infantry divisions emerged from their landing craft into a storm of machine gun fire.

The landing craft ramps dropped, and men walked directly into interlocking fields of fire that the Germans had registered months before. Many were killed before they reached the water’s edge. Others drowned under the weight of their equipment in water that was deeper than expected. The rough seas and strong currents had pushed many craft off course, landing them in front of the strongest German positions.

Those who made it to the sand found themselves pinned down behind a low seaw wall with no cover and no way forward. The scene on the beach defied description. Bodies lay in the surf, rolling with each wave. Wounded men screamed for medics who could not reach them. Equipment burned everywhere. The carefully rehearsed assault tactics disintegrated in the chaos.

Officers who were supposed to lead their men forward were dead. Sergeants who were supposed to maintain unit cohesion were scattered across hundreds of yards of beach. Men who had trained together for months found themselves alone among strangers. Pinned down by fire, they could not escape.

Company A of the 116th Infantry Regiment suffered the worst fate. They landed directly in front of the strongest German positions near Verville. Within 10 minutes, the company had ceased to exist as a fighting unit. Every officer and sergeant was dead or wounded. The few survivors huddled in the surf, unable to advance or retreat. Of the roughly 200 men who waded ashore that morning, only a handful would survive the day unwounded.

The amphibious tanks that were supposed to support the infantry had mostly sunk. The 741st tank battalion had been assigned to provide armored support for the assault on the eastern half of Omaha Beach. Their duplex drive tanks were modified. Shermans equipped with inflatable canvas screens and propellers that allowed them to swim from their landing craft to the beach.

The technology worked in calm water. The English Channel on June 6th was not calm. The battalion commander launched 29 of his 32 tanks 6,000 yds from shore in 6 ft swells. These tanks were designed to float in seas with waves no higher than 1 ft. The moment they entered the water, the waves began swamping their canvas screens.

27 of the 29 sank within minutes. The crews went down with them, trapped inside steel coffins on the floor of the English Channel. Only two tanks from the launched group reached the beach under their own power. Three more were landed directly from a landing craft whose crew recognized the impossibility of the sea conditions.

The 741st tank battalion, which was supposed to provide crucial armored support, arrived at Omaha Beach with only five tanks operational. The 743rd tank battalion on the western half of the beach fared better only because their naval officer refused to launch in the heavy seas. Lieutenant Dean Rockwell ordered the landing craft to carry the tanks all the way to the beach rather than launch them offshore.

This decision violated orders but saved most of his tanks. The 743rd lost only nine vehicles to enemy fire rather than losing nearly all of them to the sea. By 8:00, 2 hours after the first landing, the assault had stalled completely. Bodies covered the beach. Equipment burned in the surf. Small groups of survivors crouched behind the seaw wall and any other cover they could find, unable to advance against the German fire.

The carefully planned timetables were meaningless. The beach exits remained firmly in German hands. Vehicles and supplies were stacking up offshore because there was nowhere safe to land them. A beach master sent a message to Admiral Hall’s flagship, reporting that they were stopping the advance of follow-up waves. There was no point in landing more troops until the men, already ashore, could move off the beach.

Another observer reported that the situation was critical. Men were being cut to pieces by German fire that the preliminary bombardment had failed to suppress. Aboard the Augusta, Bradley received fragmentaryary and terrifying reports. One message from a naval observer simply said, “Entire first wave founded.” Another reported that troops were being cut to pieces.

The beach obstacles that the army engineers were supposed to clear remained intact because the engineers had been killed before they could reach them. Bradley stood on the bridge of his command ship, watching through binoculars as smoke rose from the distant beach, and considered the unthinkable possibility that the invasion might fail.

This was the moment when the plan collapsed entirely. The staff officers who had designed the invasion had assumed the preliminary bombardment would work. They had no contingency for what happened when it failed. The troops on the beach had no artillery support because the field guns were still floating offshore on landing craft that could not reach the sand.

Air support was ineffective because the pilots could not distinguish friendly positions from enemy ones in the chaos below. The beach was dying and no one in the chain of command had a solution. What saved Omaha Beach was not a general’s strategy or a staff officer’s plan. It was the initiative of individual commanders who saw what needed to be done and did it without waiting for orders.

On the beach, officers like Colonel George Taylor and Brigadier General Norman Kota rallied survivors and led them forward through the German fire. At sea, the captains of a handful of destroyers decided that the rules no longer applied. Commander Robert Oakley Beer had graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1932, the same year Franklin Roosevelt was first elected president.

He was born in Genoa, Nebraska on April 6, 1910. the son of a small town family with no naval tradition. He had chosen the academy because it offered a free education and a chance to see the world. By 1944, he had spent 12 years in uniform and risen to command his own ship. Beer was tall, lanky, and calm under pressure. Historian Craig Simmons described him as the kind of officer who inspired confidence in his crew through competence rather than charisma.

He had taken command of the Karmic in August 1943 and spent the following months training his crew for the invasion everyone knew was coming. By June 1944, the Karmic was a tight ship with an experienced crew ready for combat. The night before the invasion, Beer gathered his crew and made an announcement over the ship’s intercom.

“Now hear this,” he said. “This is probably going to be the biggest party you boys will ever go to. So, let us all get out on the floor and dance.” It was the kind of dark humor that fighting men understood. Tomorrow, they would face German guns. Tonight, they could laugh about it.

The Carmik was a Gleavesclass destroyer 348 ft long and displacing about 1,600 tons. She was named for Major Daniel Carmik, a Marine Corps officer who had served aboard the Constitution during the Quasi War with France and been wounded leading Marines at the Battle of New Orleans. The ship had been commissioned in December 1942 at the Seattle Tacoma ship building company and had spent 1943 working up and preparing for combat operations.

She mounted four 5-in 38 caliber guns in single turrets, the standard dualpurpose weapons of the United States Navy in World War II. These guns could fire 15 rounds per minute when the crews were working at peak efficiency. Skilled crews could achieve even higher rates for short bursts, up to 22 rounds per minute when the ammunition supply allowed.

The ship had arrived off Normandy carrying 1,500 rounds of ammunition for these guns. By the end of the day, she would expend nearly all of it. Destroyers were not supposed to operate close to shore. Their thin hulls offered no protection against coastal artillery. A single hit from a German 88 could punch through their armor and detonate inside the ship.

They drew 13 ft of water and had limited maneuverability in the shallows. Running a ground on a sandbar while under enemy fire would be fatal. The official orders placed destroyers in fire support lanes 5 to 7,000 yards offshore where they could engage targets called in by shore fire control parties equipped with radios.

The problem was that the shorefire control parties were dead, wounded, or unable to communicate. These were army teams equipped with radios who were supposed to accompany the infantry ashore and direct naval gunfire onto precise targets. They carried signal panels and smoke grenades to mark positions for the ship’s offshore, but the chaos of the landing had destroyed this system before it could function.

The radios had been destroyed or waterlogged in the landing. The artillery observers who were supposed to direct naval gunfire were pinned down on the beach with the infantry they were meant to support. General Cota found one shore fire control party around 8:00 and told them it was unwise to designate a target.

The destroyers had the firepower to help, but no one was telling them where to shoot. Captain Harry Sanders changed everything. Sanders commanded Destroyer Squadron 18 from his flagship Frankfurt. He was a graduate of the Naval Academy class of 1923. a veteran officer who had seen combat in the Mediterranean campaigns and understood that rigid obedience to plans could be fatal when those plans had failed.

His men called him Savvy Sanders and the nickname fit. When the Frankfurt arrived close to the beach around 9 in the morning, Sanders saw the disaster unfolding and made a decision that would define the battle. The men on the beach were dying. The pre-planned fire support system had collapsed. The only way to help them was to close the range and shoot at what he could see.

Sanders ordered all destroyers in his squadron to close the beach as far as possible and provide direct fire support. This meant ignoring the 5,000yard limit. It meant operating in water barely deep enough to float their ships. It meant exposing thin-kinned vessels to German guns that could punch through destroyer armor at pointblank range.

Sanders later estimated that the Frankfurt had only a few inches of water under her keel at times. The three fathom line 18 ft of water was the practical limit for destroyers. Several ships crossed it repeatedly that morning. Around 9:50, Rear Admiral Carlton Bryant aboard the battleship Texas made it official.

Bryant had been receiving reports from the destroyers already engaging and understood the situation demanded action. He broadcast a message over the talk between ships radio that would become famous among the destroyer crews. Get on them, men. Get on them. They are raising hell with the men on the beach and we cannot have any more of that. We must stop it.

The destroyers surged forward. The Carmik, the Makook, the Frankfurt, the Thompson, the Baldwin, the Emmens, the Doyle, and the Harding all pressed toward the beach until their keels scraped the sandy bottom. Three British Huntclass escort destroyers joined them. The destroyers moved in close to the beach, Admiral Kirk later wrote, with their boughs against the bottom.

Commander Beer brought the Karmic to within 900 yards of the beach, close enough that German soldiers could have hit the ship with rifle fire. At that range, his gunners could see individual German soldiers in the strong points. They could identify specific machine gun nests and bunkers. They could watch their shells explode against concrete fortifications and know immediately whether they had hit their targets. But there was a problem.

Beer could see the Germans, but he could not always tell exactly where to shoot. The defenders used smokeless powder, which produced no telltale puffs to mark their positions. Beer scanned the bluffs through his binoculars, looking for muzzle flashes, but the process was slow and unreliable. Then Beer noticed something that changed everything.

A group of American tanks from the 743rd Tank Battalion had managed to reach the beach near the Verville Draw, one of the five exits from the sand to the bluffs above. These tanks were firing at German positions on the hillside. Beer watched their shells impact and realized he had found his spotters.

It became evident, Beer later reported, that the army was using tank fire in the hope that fire support vessels would see the target and take it under fire. What followed was one of the most remarkable examples of improvised cooperation in military history. The tanks would fire at a target on the bluffs. Beer would watch where their shells landed and direct his own guns at the same spot.

A tank commander reportedly opened his hatch and waved at the destroyer, then began deliberately marking targets for naval gunfire. Beer called it a deadly pad, a dance of death between the ship and the tanks. Between approximately 8:50 and 10:15 in the morning, the Karmic fired 1127 rounds of 5-in ammunition.

That was roughly 13 rounds per minute from all four guns combined for 85 straight minutes. The gun crews worked with desperate efficiency, loading and firing until their weapons glowed red hot. The barrels became so hot that fire hoses had to be used to cool them so the crews could keep shooting. When the intense firing period ended, the Karmic had expended most of her ammunition supply.

The effect was devastating for the German defenders. Each 5-in shell weighed 55 lbs and carried enough explosive to destroy a machine gun position or collapse a section of trench. The destroyers were not firing blind like the battleships had done earlier from 10,000 yds out. They were engaging specific targets at pointblank range with direct observation of their hits.

When a shell struck a bunker, the gunners could see the explosion and adjust their aim for the next shot. The Germans had no answer for this assault. Their coastal artillery was positioned to engage ships at normal combat ranges, not vessels operating practically in the surf line. The guns in the bunkers could not depress far enough to engage targets so close to shore.

Meanwhile, the destroyer shells were tearing their positions apart. A German regimental commander sent a desperate message to his headquarters. Naval guns are smashing up our strong points. We are running short of ammunition. We urgently need supplies. The phone line went dead before he could receive a response. The naval shells had cut the communication wires.

Another German soldier later recalled that the naval fire was the most terrifying thing he experienced on D-Day. The shells came without warning and struck with devastating accuracy. “You could not hide from them,” he said. “They followed you wherever you went.” Hinrich Zello, a German machine gunner at Reed Stan’s Nest 62, who claimed to have fired 12,000 rounds at the Americans that morning, was eventually silenced by naval gunfire that destroyed his position.

The Carmik was not alone in this desperate work. The Makook, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Ralph Remy, fired 975 rounds during the same period. Remy pushed his ship to the three fathom line, the 18 ft depth contour that marked the absolute limit of safe navigation for a loaded destroyer. The Emmens expended 767 rounds. The Frankfurt and Thompson worked over the western beaches, supporting the infantry near Verville and the Rangers at Point Duok.

The Harding provided critical fire support for Lieutenant Colonel James Rudder’s Rangers as they scaled the 100 foot cliffs at Point Dhawk. The Rangers had been assigned to destroy a battery of heavy guns that could threaten the entire invasion fleet. They climbed the cliffs under fire only to discover the guns had been moved.

The Harding kept German reinforcements at bay while the Rangers searched for and eventually found and destroyed the relocated artillery. The Satalie and Thompson supported the western flank where Rangers and infantry from the 29th Division struggled to break through the fortifications guarding the Verville exit.

These ships fired at targets they could see, improvising solutions when the planned fire control system collapsed across the entire beachfront. American destroyers were ignoring their safety margins and driving straight toward the guns. The ships operated at extreme risk. The Baldwin took two hits from German artillery, shells that damaged her for castle and gunmount, but miraculously killed no one.

The Emmens narrowly avoided a salvo that would have destroyed her. small arms. Fire from the bluffs struck the super structures of several ships, but the destroyers kept firing. The turning point came late in the morning. The sustained naval fire had suppressed enough German positions that small groups of infantry could finally begin moving off the beach.

Colonel George Taylor of the 16th Infantry Regiment gathered a group of survivors near the seaw wall and delivered words that would become legend. There are two kinds of people who are staying on this beach, he said. Those who are dead and those who are going to die. Now, let us get the hell out of here.

Brigadier General Norman Cota of the 29th Division was even more direct. Cota was 51 years old on D-Day, far older than most of the men he commanded. He had landed around 7:30 and spent two hours watching his men die while pinned down at the water line. He moved along the seaw wall under fire, rallying survivors and organizing attacks on the bluffs.

His example inspired men who had given up hope. “Gentlemen, we are being killed on the beaches.” He told one group, “Let us go inland and be killed.” It was dark humor, but it made the point. Staying on the beach meant certain death. Moving forward at least offered a chance. When Cota encountered soldiers from the fifth ranger battalion huddling behind the seaw wall, he asked what outfit they were. Rangers, they replied.

Cota nodded, “Well, god damn it then, Rangers, lead the way.” That phrase became the official ranger motto. Born in blood on Omaha Beach. Cota personally supervised the placement of Bangalore torpedoes to blow gaps in the barbed wire blocking the route off the beach. He led soldiers through the gaps and up the bluffs toward the German positions.

For his actions that day, he received both the Distinguished Service Cross and the British Distinguished Service Order. The combination of destroyer fire support and inspired leadership on the beach finally broke the deadlock. By 10:43 the Makook reported American troops advancing off the beach. By 1100 hours the first elements had reached Vville.

The drawers that had been impossible death traps in the morning were finally opening up. The Carmik and her sister ships had punched the first holes in the German defenses. The destroyers had done what the battleships and bombers could not. They had provided accurate sustained fire support at the critical moment when the invasion hung in the balance.

General Bradley later wrote in his memoir, A Soldier’s Story, that the Navy Saved Our Hides. Here I must give unstinting praise to the United States Navy. As on Sicily, the Navy saved our hides. 12 destroyers moved in close to the beach, heededless of shallow water, mines, enemy fire, and other obstacles to give us close support.

The main batteries of these gallant ships became our sole artillery. Colonel Stanh Hope Mason, the chief of staff of the First Infantry Division, was even more emphatic. I am now firmly convinced that our supporting naval fire got us in. Without that gunfire, we positively could not have crossed the beaches.

Major General Leonard Gerro, commanding the fifth corps that landed at Omaha, sent a message to Bradley that evening with just six words. Thank God for the United States Navy. His assistant, Colonel BB Thally, sent a similar message shortly before noon. I join you in thanking God for our Navy. The anonymous beachmaster, whose earlier reports had been so grim, changed his assessment as the day progressed.

“You could see the trenches, guns, and men blowing up where they were hit,” he reported. “The few Navy destroyers that we had there probably saved the invasion. The price of the morning’s failure was terrible. By the end of June 6th, American forces at Omaha Beach had suffered over 2,000 casualties, killed, wounded, and missing.

Some estimates placed the figure higher at 3,000 or more. The First Infantry Division alone suffered over 1,000 casualties. The 29th Infantry Division, in its first combat action of the war, was devastated. Many of these losses occurred in the first few hours when the men were trapped on the beach without effective support.

The exact whole will never be known because so many bodies were lost to the sea or buried in hasty graves that were later obliterated by the fighting. But the beach head held. By nightfall, American forces had established positions a mile or more inland in some sectors. The beach exits were open. Vehicles and supplies were flowing ashore.

The German counterattack that could have thrown the Americans back into the sea never materialized because the 352nd division had been bled white defending the beach. They had no reserves left to commit. The contrast with what might have been was stark. If the destroyers had not intervened, if they had obeyed their orders and stayed safely offshore, the men on the beach would have continued dying with no way off the sand.

Bradley’s contingency plan to evacuate the beach head might have become necessary. The entire invasion timetable could have been thrown into chaos. The war might have lasted months or years longer. The destroyer crews emerged from the battle largely unscathed. The caric sustained no casualties on D-Day.

Early in the morning, German shore batteries had opened fire on the ship. Beer silenced them quickly with his own guns. The ship’s decklog recorded the engagement simply. German shore battery opened fire on this ship. German shore battery silenced by main battery of this ship. No damage resulting from enemy fire.

The only destroyer lost in Operation Neptune was the Cory at Utah Beach, which struck a mine and sank with 22 killed and 33 wounded. Among the destroyers at Omaha, only the Baldwin took significant hits, struck by two shells from German artillery that damaged her equipment, but killed no one. The thin skinned tin cans had driven straight into the teeth of German coastal defenses and survived.

The question that haunted military planners afterward was simple. Why had it taken so long for the destroyers to move in? The answer revealed a fundamental flaw in the invasion planning. The operation had been designed around assumptions that proved false and there was no contingency when those assumptions failed.

The planners assumed the preliminary bombardment would suppress the beach defenses. It did not. They assumed the aerial bombing would devastate the German positions. It missed completely. They assumed the amphibious tanks would provide armored support for the infantry. Most of them sank. They assumed shorefire control parties would direct naval gunfire onto precise targets.

Those parties were killed or unable to communicate. They assumed the Germans would be demoralized and disorganized. Instead, the defenders were ready and waiting. At every point where the plan depended on something working, that something failed. The fundamental error was overconfidence. The planners had convinced themselves that the preliminary bombardment would work because they needed it to work.

They had not seriously considered what would happen if it failed because failure was not supposed to be possible. This was the same overconfidence that had led German planners to underestimate American industrial capacity 2 years earlier. It was the kind of thinking that loses wars. Admiral Hall had tried to warn them.

He had pointed out that 40 minutes of bombardment was inadequate for the task. He had requested more time and more ammunition. He had been overruled by planners who were more concerned with maintaining surprise than with ensuring the beach defenses would actually be destroyed. Hall was right, and the men on the beach paid the price for ignoring his advice.

What saved the invasion was human initiative. Commanders like Sanders and Beer saw what needed to be done and did it without waiting for orders from the chain of command. They understood that following the letter of their instructions would result in catastrophe, so they followed their judgment instead.

This was exactly the kind of flexibility that rigid military planning often discourages. The destroyers demonstrated something else as well. The courage required to close with an armed enemy at pointblank range, accepting terrible personal risk to help men you cannot see, represents a particular kind of valor. These vessels had no armor to speak of, nothing between their crews and the ocean but thin steel plate.

They operated at the extreme edge of navigable water, risking grounding on every approach. One mine, one lucky shell, one hidden sandbar could have ended any of them. They went anyway. Commander Beer continued in command of the Karmic through the rest of the Normandy campaign. The ship remained off the beach head until June 17, providing fire support as the army expanded its foothold.

4 days after D-Day, the Karmic shot down a German Hankle bomber that was attacking the invasion fleet. In August 1944, the Carmik participated in Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France. On August 18, she destroyed a German patrol boat in the Mediterranean. The ship compiled an impressive combat record across two theaters of the European War.

After the war in Europe ended, the Karmic entered the Philadelphia Navyyard for conversion to a high-speed mine sweeper, receiving the new designation DMS33. She served in the Pacific during the occupation of Japan, sweeping mines from the Yellow Sea and coastal waters. When the Korean War erupted in 1950, the Karmic returned to combat operations.

In October 1950, the ship earned the Navy unit commendation for mind sweeping operations at Chinampo Harbor, clearing the approaches so that United Nations forces could use the port. She completed two Korean war deployments before being decommissioned in February 1954 at San Francisco. Beer himself rose through the ranks after the war.

He served as captain and then as assistant chief of staff for plans and operations with the amphibious force far east during Korea. He earned the Bronze Star with combat distinguishing device for his service there. He eventually retired from the Navy as a rear admiral in 1959 having served 27 years in uniform. For his actions at Normandy, Beer received the Silver Star.

The citation from Commander Naval Forces Europe praised his conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against German coastal defenses and troop concentrations. It noted that Commander Beer skillfully and efficiently handled his ship and directed the fire of his batteries so that this fire support was invaluable aid to our own forces.

He died on February 13, 1990 at the age of 79 and was buried in the United States Naval Academy cemetery at Anapapolis. The caric herself met a less glorious end. She was struck from the naval vessel register in July 1971 after 17 years of inactive status. In August 1972, she was sold for scrap and broken up in a California shipyard.

Nothing remains of the ship that fired 1127 shells to save Omaha Beach. No museum preserves her. No memorial marks where she fought. Like most of the ships and men who won the war, she simply vanished into history. The men who served aboard her scattered back to civilian life. Some stayed in the Navy and made careers of it.

Others returned to farms, factories, and offices. across America. They had done something extraordinary on a single morning in June, and then they went home and became ordinary citizens again. Most never spoke much about what they had seen and done. The lessons of Omaha Beach remained controversial for decades. Some historians blamed Bradley for inadequate planning.

Others faulted the air commanders whose bombs fell miles from their targets. Still others pointed to the intelligence failure that missed an entire German division in the coastal defenses. Everyone had someone else to blame for the chaos of the morning. But the deeper lesson was about the limits of planning itself.

No operation of such complexity can anticipate every contingency. Somewhere somehow something will go wrong. The question is not whether the plan will survive contact with the enemy. The question is, what happens when it does not? At Omaha Beach, the answer came from destroyer captains who understood that initiative matters more than obedience when lives are at stake.

They could not fix the bombing that missed. They could not resurrect the tanks that sank. They could not restore communications with the shorefire control parties, but they could drive their ships into the shallows and shoot at what they could see, and that was enough. The naval historian Samuel Elliot Morrison, who wrote the official history of the United States Navy in World War II, concluded that the destroyers saved the day at Omaha Beach.

He was not exaggerating. Without their intervention, the landing might well have failed entirely. The troops on the beach were pinned down, unable to advance, slowly being destroyed. Only the destroyers could provide the fire support needed to break the deadlock. This was not what anyone had planned. The destroyers were supposed to stay safely offshore, engaging targets called in by forward observers.

When that system collapsed, the captains had to improvise. They had to assess the situation, decide what needed to be done, and act on their own judgment. It was leadership in its purest form, command decisions made in the chaos of battle by men who could see what others could not. The story of the karmic and her sister ships carries a message that extends beyond military history.

It is about what happens when well-laid plans fail and individuals must decide whether to follow rules or follow conscience. The destroyer captains at Omaha Beach chose conscience. They saw men dying and did what they could to help regardless of the risk to themselves and their ships. That choice made the difference between victory and defeat.

80 years have passed since the guns of the Karmic fell silent off the coast of Normandy. The ship is gone, broken up for scrap in a California shipyard. Commander Beer died in 1990 at the age of 79. The veterans who remember that morning grow fewer each year. Soon there will be no one left who was there. No one who can describe from personal experience what it was like to see those destroyers emerge from the smoke and begin firing. But the story remains.

On a single June morning, when everything that could go wrong did go wrong, a handful of naval officers refused to accept failure. They pushed their ships into the shallows, risked grounding on sandbars and striking mines, and delivered the fire support that the army desperately needed. They did not wait for orders.

They did not ask permission. They saw what needed to be done, and they did it. The caric fired 1127 shells in 85 minutes on June the 6th, 1944. Those shells helped break open the Verville drawer and allowed American soldiers to finally move off the beach. It was one ship among many that day, but it was enough.

Sometimes one ship, one captain, one moment of initiative is all that stands between victory and disaster. That is the lesson of Omaha Beach. Plans fail. Assumptions prove wrong. The carefully designed operation falls apart on contact with reality. What matters then is not the plan. What matters is the courage and judgment of the individuals who must decide what to do when the plan is gone.

The destroyer captains at Omaha Beach had both. And because they did, the invasion succeeded. If you found this story as compelling as we did, please take a moment to like this video. It helps us share more forgotten stories from the Second World War. Subscribe to stay connected with these untold histories. Each one matters.

Each one deserves to be remembered and we would love to hear from you. Leave a comment below telling us where you are watching from. Our community spans the globe. From veterans and their families to history enthusiasts of all ages, you are part of something special here. Thank you for watching and thank you for keeping these stories alive.

News

Why German Generals Said Patton’s ApacheSoldiers Were Worse Than Hell D

In the summer of 1943, the Mediterranean sun was an unforgiving hammer beating down on the shores of Sicily….

They Laughed at the “Tea-Drinking Soldiers” — Until the British Showed Them How to Survive D

June 7th, 1944. Morning light cuts through the smoke drifting across Normandy’s hedgeros. Sergeant Bill Morrison of the 29th…

Japanese Thought They Surrounded Americans — Then Marines Wiped Out 3,200 of Them in One Night D

July 25th, 1944. The Fonte Plateau, Guam. In the thick tropical darkness, 3,200 Japanese soldiers moved through the jungle…

Germany Stunned by America’s M18 57mm Recoilless—And Their Panzerfaust Was Outranged D

Vasil, Germany, March 24th, 1945 0900 hours. And Private Firstclass Donald Wagner of the 17th Airborne Division’s 513th parachute…

Germans Never Expected M18 Hellcat Tank Destroyers To Outrun Their Panzers D

September 19th, 1944. 0730 hours. Bison La Petite, Lorraine, France. The morning fog hung thick across the French countryside…

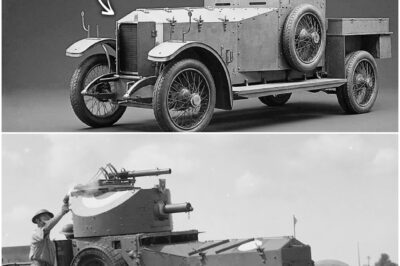

The ‘Elegant’ British Armoured Car That Fought In Two World Wars Without Becoming Obsolete D

September 1914, a shipyard in Dunkirk, Northern France. Commander Charles Rumley Samson of the Royal Naval Air Service watched…

End of content

No more pages to load