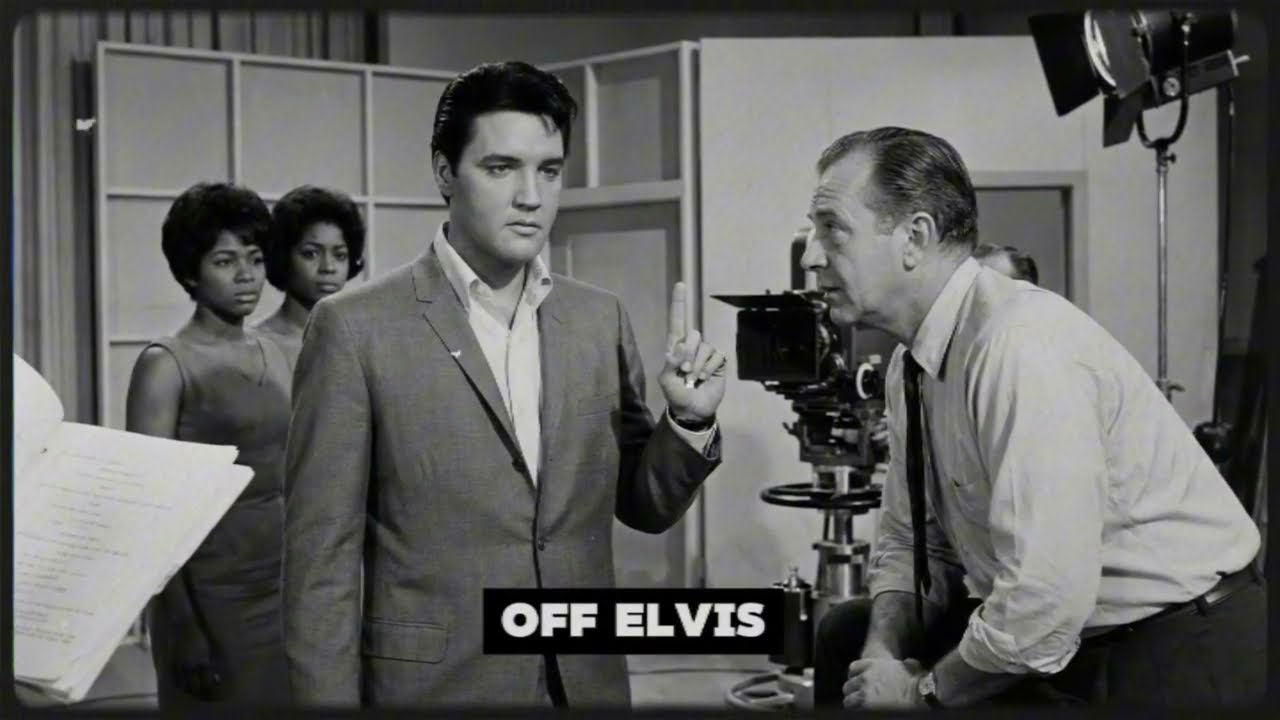

June 1965, Paramount Studios, Hollywood. Elvis Presley was in the middle of filming his 17th movie. The production was running smoothly until Harold Weinstein, the studio head, requested a private meeting. Elvis walked into Weinstein’s office expecting to discuss scheduling or script changes. Instead, Weinstein closed the door and said something that would test everything Elvis believed in.

“We need to talk about your backup singers, the black girls. They’re creating problems with the southern markets. We need to replace them.” Elvis’s response was one word, just one word, but it ended the conversation immediately and became a story that nobody would hear about until decades later. This is the story of the moment Elvis drew a line he would never cross and what it cost him to stand by his principles.

It was June 1965 and Elvis was at the peak of his Hollywood career. He was making three movies a year, each one profitable, each one following a similar formula. The studios loved him because he was reliable, professional, and box office gold. Elvis was less enthusiastic about the movies themselves, feeling increasingly trapped in a cycle of lightweight musicals that didn’t challenge him as an artist.

But he showed up, did the work, and maintained relationships with the people who controlled his career. For this particular film, Elvis had insisted on bringing in a new group of backup singers. He’d discovered them performing at a small club in Los Angeles. Four young black women with voices that reminded him of the gospel music he’d grown up loving.

Their names were Patricia, Denise, Lorraine, and Angela. They were talented, professional, and grateful for the opportunity to work with Elvis. This was their first major film, their big break. Elvis had personally vouched for them, had argued for their inclusion in the production. The first two weeks of filming had gone well.

The backup singers had nailed every take, their harmonies adding depth and soul to the musical numbers. The director was pleased. The music supervisor was impressed. But then Harold Weinstein, the studio head, started receiving letters, dozens of them, from theater owners in the South. We’re concerned about the racial composition of the musical numbers.

Our audiences might be uncomfortable. Is there a way to reshoot with different singers? Weinstein had dealt with this before. Southern theater owners were often worried about anything that suggested racial integration, even in entertainment. Usually, the solution was simple. Use creative camera angles. Keep certain performers in the background.

Make the integration less obvious. But in this film, Elvis’s musical numbers featured the backup singers prominently. They were visible. They were talented and they were undeniably black. Weinstein decided he needed to have a conversation with Elvis. On a Wednesday afternoon during a break in filming, Weinstein’s assistant approached Elvis.

Mr. Weinstein would like to see you in his office when you have a moment. Elvis, still in costume from the previous scene, nodded. Give me 10 minutes to change. Elvis walked to Weinstein’s office, expecting a routine production meeting. Weinstein’s office was exactly what you’d expect from a studio head, large, expensively furnished with photographs of every major star who’d worked for Paramount lining the walls.

Weinstein was behind his desk, looking uncomfortable. That should have been Elvis’s first warning that something was off. Elvis, sit down. Thanks for coming. Elvis sat in the leather chair across from Weinstein’s desk. What’s up? Something wrong with the production? Weinstein shifted in his seat. The production is fine. You’re doing great work as always, but we have a situation that needs to be addressed.

Elvis waited. Weinstein continued, choosing his words carefully. We’ve been hearing from some of our exhibitors, theater owners in the South primarily. They’re concerned about the musical numbers in the film. Elvis frowned, concerned how. The numbers are good. The music supervisors said they’re some of the best we’ve recorded.

Weinstein nodded. The music is excellent. That’s not the issue. The issue is, well, the composition of your backup singers. Elvis felt something cold settle in his stomach. He knew exactly where this was going. The composition? Elvis repeated flatly. Weinstein pressed on, his discomfort obvious. Your backup singers are very talented.

Nobody’s questioning their ability, but they’re creating some concerns with our southern markets. Theater owners are worried about audience reactions. Elvis’s voice was quiet, but hard. Audience reactions to what exactly? Weinstein side. Elvis, you know how it is. The South is still sensitive about integration. Having black performers so prominently featured in the musical numbers, it’s making some people uncomfortable.

We’re worried it could hurt the box office in those markets. Elvis sat very still. So, what are you asking me to do? Weinstein tried to make it sound reasonable. We’re asking you to consider using different backup singers. We have several very talented white performers who could step in. We could reshoot the musical numbers.

It wouldn’t add much time to the production schedule. Elvis stood up. Not quickly, not aggressively. He just stood, looked at Weinstein, and said one word. Never. Weinstein blinked. Elvis, let’s talk about this rationally. But Elvis was already walking toward the door. He stopped with his hand on the doornob, turned back to Weinstein.

I grew up poor in Mississippi. I learned music from black artists. Gospel, blues, everything that matters in my music came from black musicians who were generous enough to share it with me. Those girls you want me to fire, they’re the most talented singers I’ve worked with in 5 years of making these movies.

And you want me to replace them because theater owners in the South might be uncomfortable? Weinstein started to respond, but Elvis wasn’t done. Here’s what’s going to happen. Those singers stay. Every musical number we’ve filmed, it stays exactly as it is. And if your Southern Theater owners have a problem with that, they don’t have to show the movie.

But I’m not firing talented artists because of racism. Not now. Not ever. Elvis opened the door and walked out, leaving Weinstein sitting behind his desk in stunned silence. Elvis went straight to his dressing room, his hands shaking with anger. He sat down and tried to calm himself. Within 15 minutes, there was a knock on his door. It was the production coordinator. Mr.

Presley, Mr. Weinstein would like to speak with you again. Elvis looked at her. Tell Mr. Weinstein we’ve said everything we need to say. The coordinator looked uncomfortable. He said it’s important about the production schedule. Elvis sighed. Fine, but we’re talking here, not in his office. 5 minutes later, Weinstein arrived at Elvis’s dressing room.

His demeanor had changed. He looked less like a studio head delivering orders and more like someone who’d realized he’d made a mistake. Elvis, I spoke with the other producers. We’re going to keep your singers. The musical numbers stay as filmed. Elvis studied him. What changed? Weinstein sat down heavily. Honestly, two things. First, you’re Elvis Presley.

You are the biggest star in Hollywood right now. We’re not going to risk our relationship with you over backup singers. Second, and I’m being honest here, you were right. It was wrong of me to ask. I let myself be pressured by theater owners instead of standing up for what was right. Elvis nodded slowly. “So, we’re clear.

Patricia, Denise, Lorraine, and Angela stay on this production and any future productions I’m involved with?” “Absolutely clear,” Weinstein confirmed. Elvis’s anger faded slightly. “And the Southern theaters?” Weinstein shrugged. “They’ll show the movie or they won’t. We’ll lose some box office in a few markets maybe, but we’ll survive and we’ll be on the right side of history.

After Weinstein left, Elvis sat alone in his dressing room for a long time. He thought about calling the backup singers, telling them what had almost happened. But then he decided against it. They didn’t need to know. They didn’t need to carry the weight of almost losing their big break because of racism.

They could just keep working, keep being talented, keep building their careers. Elvis never told the four singers what had happened. He continued working with them professionally, treating them the same respect he showed everyone on set. They finished the film without incident. The musical numbers were, as Elvis had said, some of the best he’d recorded for any of his movies.

When the film was released, it did lose some box office in certain southern markets. A few theaters refused to show it. Others showed it but faced protests. But the film was profitable overall and Elvis’s star power carried it through. The backup singers went on to have successful careers. Patricia and Denise formed their own group.

Lorraine became a solo artist. Angela eventually moved into music production. None of them knew during those years that Elvis had gone to bat for them, had been willing to jeopardize his relationship with the studio to keep them on the production. The story remained buried in studio archives and the memories of the few people who’d been directly involved.

It wasn’t until 2003, 38 years later, that the story came to light. Denise, now in her 60s, in doing an interview for a documentary about session singers of the 1960s, mentioned that she’d always wondered why Elvis had been so consistently supportive of black performers when many of his contemporaries weren’t.

The documentary filmmaker did some digging and found someone who’d worked at Paramount in 1965, someone who remembered the confrontation between Elvis and Weinstein. When Denise learned what had happened, what Elvis had done for her and her fellow singers, she broke down crying during an interview. “I had no idea,” she said.

“I knew Elvis was good to work with, knew he treated us professionally, but I never knew he’d risked his career for us. He could have easily replaced us, and we never would have known.” The other surviving singers had similar reactions when they learned the truth. Patricia said, “Elvis never made a big deal out of it.

He never told us what he’d done. He just treated us like professionals and let us do our jobs. That’s real integrity.” Not doing the right thing for praise, but doing it because it’s right. When word of the story spread through the music community, other black artists who’d worked with Elvis came forward with their own stories.

Stories of Elvis insisting on integrated audiences at his concerts. Stories of Elvis refusing to perform at venues that wouldn’t allow black patrons. Stories of Elvis paying black musicians the same rates as white musicians when that wasn’t standard practice. What emerged was a pattern of quiet principle of Elvis consistently using his power to push back against racism without seeking credit or attention for it.

Music historian Marcus Williams analyzed Elvis’s actions in context. Elvis came from the segregated South. He could have easily gone along with the racist practices of the entertainment industry. Nobody would have blamed him. But instead, he used his power and influence to create small but significant changes. He didn’t make grand political statements.

He just refused to participate in discrimination. That took real courage, especially in the 1960s. The incident with Weinstein and the backup singers became a teaching moment in film schools and music business classes. This is what power looks like when it’s used responsibly. Professors would say Elvis didn’t owe those singers anything beyond professional courtesy, but he recognized that he had leverage and he used it to protect people who couldn’t protect themselves.

What makes the story particularly powerful is what Elvis didn’t do. He didn’t hold a press conference. He didn’t give interviews about his principled stand. He didn’t use the incident to burnish his own image. He simply drew a line, said never, and walked away. The backup singers got to keep working, got to build their careers, never knowing that their big break had almost been taken away because of racism, and had been saved by one word from Elvis Presley.

Years later, when asked about Elvis’s legacy, Denise said something that captured the essence of who Elvis was. People focus on the music, the performances, the fame. But Elvis’s real legacy is in the small moments nobody saw. The times he stood up for what was right when nobody was watching, the times he used his power to help people who couldn’t help themselves.

That’s the Elvis we should remember. Today, the story of Elvis and the one-word response is used as an example of moral courage in leadership seminars and ethics classes. Not because it was dramatic or public, but because it was simple and private. Elvis didn’t need applause or recognition to do the right thing.

He just needed to know in his own heart that he’d stood up for people who deserved his support. In a life filled with spectacular performances and public moments, this quiet act of principle might be one of the most important things Elvis ever

News

Elvis Received Letter from Vietnam Soldier — His Response SAVED Soldier’s Life

March 1969, Graceand, Memphis. Elvis Presley received thousands of fan letters every week. Most were read by staff, answered with…

Elvis and Johnny Cash Sang GOSPEL Together in a Small Church — The World Was NEVER Meant to Know

August 1974, Memphis, Tennessee. Two of the biggest names in American music were both in crisis. Elvis Cresley was struggling…

Elvis’s Car Broke Down in a Neighborhood He Was WARNED About — Then Everything STOPPED

June 1967, Memphis, Tennessee. Elvis Presley was driving through a neighborhood he’d never visited before, one that his security team…

Elvis’s guitar string BROKE on live TV — what he did with it became ICONIC

September 9th, 1956. Ed Sullivan Show, CBS Television Studio 50, New York City. Elvis Presley was performing in front of…

Elvis’s Microphone Died on LIVE TV — Ed Sullivan Witnessed a Moment That CHANGED Television

September 9th, 1956, CBS Television Studio 50, New York City. Elvis Presley was performing on the Ed Sullivan Show in…

Elvis heard Sam Cooke for first time — what he did next SHOCKED the music world

March 1960, Graceland, Memphis. Elvis Presley was sitting in his living room with some friends when someone put on a…

End of content

No more pages to load