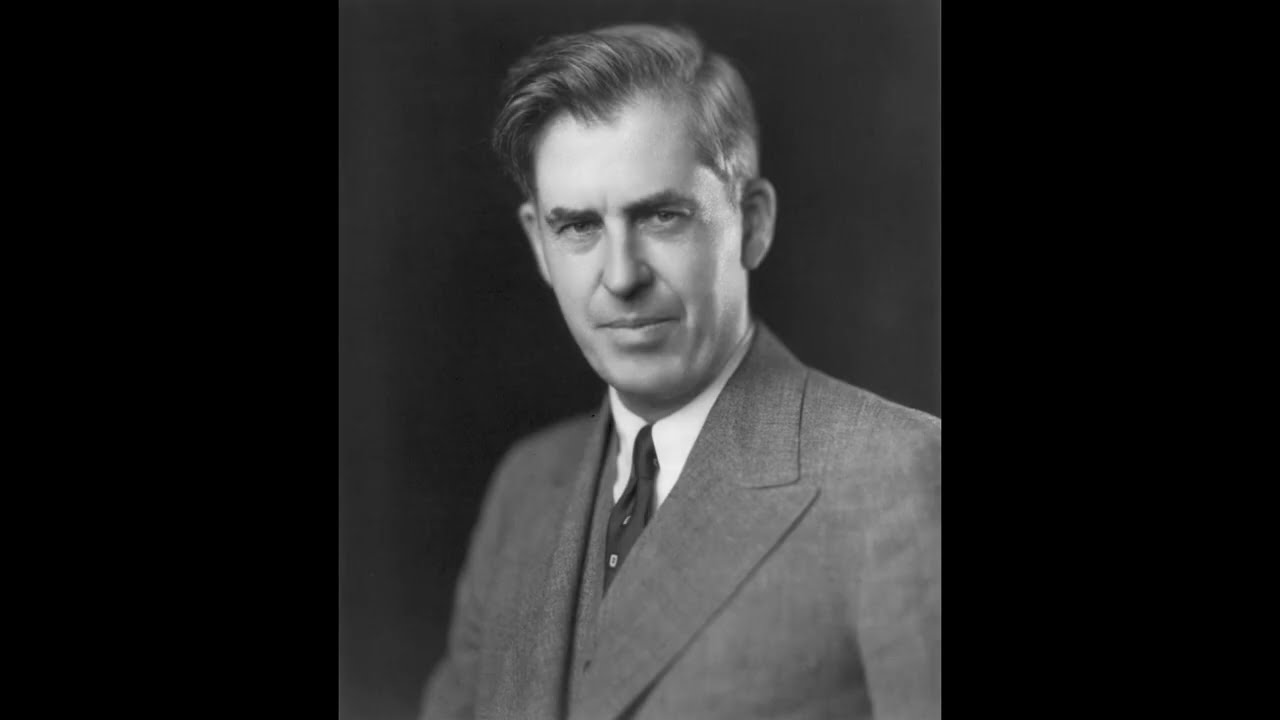

September 20th, 1946. Henry Wallace sat in his Commerce Department office, staring at the phone. Harry Truman had just fired him. The president’s voice had been polite but firm. The decision was final. Wallace had been vice president of the United States from 1941 to 1945. He had sat across from Franklin Roosevelt in cabinet meetings while they planned the war effort.

He had traveled the world as FDR’s personal representative. He had been one heartbeat away from the presidency for four years. Now he was unemployed, fired by a man he considered an accident of history who never should have been president in the first place. Wallace picked up the phone and called his closest adviserss.

He told them he was accepting a position as editor of the New Republic. From that platform, he would attack Truman’s policies relentlessly. He was going to prove to the American people that Truman had stolen Roosevelt’s legacy and was leading the country toward World War II. The advisers warned him this would be political suicide.

Wallace didn’t care about his political career anymore. He cared about stopping what he saw as Truman’s catastrophic foreign policy. He believed Truman was betraying everything Roosevelt had worked for. What followed was one of the most systematic campaigns to destroy a sitting president from within his own party.

Wallace would give speeches in every major city attacking Truman’s policies. He would write articles accusing Truman of wararmongering. He would eventually run against Truman as a third party candidate in 1948 and he would come closer to succeeding than anyone realized. Henry Wallace believed he was the rightful heir to Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency. This wasn’t paranoia.

It was based on four years of reality. Roosevelt had chosen Wallace as his running mate in 1940 over strong objections from party bosses. The Democratic establishment thought Wallace was too liberal, too idealistic, too sympathetic to labor unions and civil rights. Roosevelt insisted. He told the Democratic convention he wanted Wallace or he wouldn’t run for a third term.

Wallace became one of the most active vice presidents in American history. Roosevelt sent him to Latin America, China, and the Soviet Union on diplomatic missions. Wallace chaired the Board of Economic Warfare. He gave speeches explaining Roosevelt’s vision for the post-war world. He became the public face of Roosevelt’s domestic and foreign policy.

By 1944, Wallace genuinely believed he was Roosevelt’s chosen successor. He had earned it through four years of loyal service. Then the 1944 Democratic Convention destroyed everything Wallace believed about his political future. The Democratic Party bosses hated Henry Wallace. They thought he was a dreamer who didn’t understand political reality.

They believed his liberal positions on labor and civil rights would cost Democrats votes. Most importantly, they feared what would happen if Roosevelt died and Wallace became president. In July 1944, party leaders met with Roosevelt at the White House. They told him Wallace had to go. Roosevelt was sick.

Everyone could see his health declining. Whoever was vice president would likely become president before the next term ended. Roosevelt gave in to the pressure. He agreed to replace Wallace, but left the choice of replacement open. The bosses bypassed the chaos and handpicked a safe, uncontroversial senator from Missouri, Harry Truman.

Wallace didn’t give up without a fight. He had delegates. He had passionate supporters who believed in Roosevelt’s liberal vision. On the convention floor, Wallace forces tried to force a first ballot vote before the bosses could organize against him. Chicago Mayor Ed Kelly claimed a fire hazard due to overcrowding in the stadium.

He forced an immediate adjournment just as the pro-Wallace chant was reaching its peak. When delegates returned the next day, the bosses had marshaled enough support to give the nomination to Truman on the second ballot. Wallace was out. Roosevelt tried to soften the blow. He wrote Wallace a letter saying he personally would vote for Wallace if he were a delegate.

But Roosevelt had also given party bosses a separate note, saying he would be happy with Harry Truman or William Douglas. FDR had played both sides. This was the ultimate betrayal. Wallace had been Roosevelt’s loyal soldier for four years. He had been the true believer in FDR’s vision.

But in the smoke-filled rooms of Chicago, the dying president didn’t fight for him. He offered Wallace polite words with one hand while signing his political death warrant with the other. Now he was being dumped because party bosses found him inconvenient. The man who replaced him was someone Roosevelt barely knew. When Roosevelt won re-election in November 1944, he offered Wallace the position of Secretary of Commerce.

It was a consolation prize, a cabinet seat for a man who had been vice president, a significant demotion that everyone recognized as such. Wallace accepted [clears throat] because he still believed in Roosevelt’s vision. He thought he could influence policy from inside the administration. He hoped Roosevelt would recognize his value and bring him back into the inner circle.

Then Roosevelt died on April 12th, 1945. Harry Truman became president and Henry Wallace found himself serving under the man who had replaced him. The irony was unbearable. To Wallace, Truman wasn’t just unqualified. He was a small man filling a giant’s shoes. Wallace had spent years at Roosevelt’s right hand shaping global policy.

Truman was a former habdasher from Missouri, a failed hat shop owner and a product of the corrupt Pendergas political machine. Wallace had been Roosevelt’s trusted adviser for four years. Truman had met with Roosevelt exactly twice during his three months as vice president. Yet Truman was president and Wallace was commerce secretary.

The resentment wasn’t just political, it was visceral. Truman kept Wallace in the cabinet initially. It was a gesture toward party unity. Roosevelt’s supporters needed reassurance that Truman would continue FDR’s policies. Keeping Wallace as commerce secretary sent that signal. The cabinet meetings were excruciating.

Wallace sat there watching the man who should have been his subordinate struggle with the weight of the office. Every time Truman made a decision, Wallace measured it against what Roosevelt would have done. Wallace quickly realized Truman didn’t share Roosevelt’s vision, particularly [clears throat] regarding the Soviet Union.

And that’s when Wallace decided he couldn’t stay silent. The fundamental disagreement between Wallace and Truman was about Joseph Stalin. Wallace believed Stalin could be trusted if America showed good faith. Truman believed Stalin was a dictator expanding Soviet control over Eastern Europe.

Wallace’s view came from his 1944 trip to the Soviet Union. He had toured Magadan and the Cola gold mines in Siberia. These were actually a part of the Gulog system, but NKVD handlers disguised them as volunteer labor camps with well-fed workers. Wallace famously described the camp director as a sensitive man. He came away convinced that cooperation with Stalin was possible.

Truman’s view came from watching Stalin break every agreement made at Yaltta. While Wallace saw a partner, Truman saw a predator. From the rigged elections in Poland to the looting of East Germany, Stalin was systematically dismantling the promises made at Yalta. By early 1946, Truman had adopted a policy of firmness toward Soviet expansion.

George Kennan’s long telegram had explained that Stalin only respected strength. The policy that would become known as containment was taking shape. America would resist Soviet expansion but avoid direct military confrontation. Wallace thought this was catastrophically wrong. He had seen Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

He was terrified of atomic war. Wallace believed Truman’s tough stance would provoke Stalin into aggression. He argued that if America just showed trust and cooperation, Stalin would reciprocate. Wallace made these arguments in private cabinet meetings. Truman listened politely and ignored him. Wallace wrote memos. Truman filed them away.

Wallace requested private meetings with the president. Truman was always too busy. By September 1946, Wallace was desperate. Truman wasn’t listening. The country was moving toward the confrontation with the Soviets. Wallace believed World War II was becoming inevitable unless someone stopped Truman’s policy.

He decided to go public. September 12th, 1946, Henry Wallace stood before 20,000 people packed into Madison Square Garden in New York City. He was there to give a speech about foreign policy. He had cleared the speech with Truman’s staff, or so he claimed. What Wallace told that crowd contradicted everything Truman’s Secretary of State was saying in Europe at that exact moment.

While James Burns was in Paris negotiating with the Soviets from a position of strength, Wallace was in New York arguing America needed to show trust and cooperation. Wallace told the crowd that Truman’s policy of firmness was pushing the world toward war. He said America’s atomic weapons were making the Soviets paranoid. He argued that Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe was defensive, not aggressive.

He claimed Stalin would allow free elections if America stopped being confrontational. The crowd loved it. These were liberals who wanted to believe Roosevelt’s vision of post-war cooperation with the Soviets was still possible. They were terrified of another war. Wallace was telling them what they wanted to hear. The press reaction was immediate and explosive.

Reporters pointed out that Wallace had directly contradicted American foreign policy while serving in Truman’s cabinet. Foreign policy experts noted that Wallace’s speech would be seen in Moscow as a sign of American division and weakness. James Burns was furious. He cabled Truman from Paris, demanding to know if Wallace’s speech represented administration policy.

If it did, Burns would resign. If it didn’t, Wallace needed to be silenced. Truman was in a political trap. When reporters asked if he had approved Wallace’s speech, Truman told them he approved the whole speech. He hadn’t actually read it carefully. Wallace’s staff had submitted it for review, and Truman had waved it through without paying attention.

Truman spent a week trying to manage the crisis. He issued a statement saying Wallace’s speech was his personal opinion, not administration policy. This satisfied no one. How could a cabinet member have a personal opinion that contradicted the president’s foreign policy? Wallace refused to back down. He gave interviews defending his speech.

He said the American people deserved a debate about foreign policy. He implied that Truman’s advisers were wararmongering. He suggested Roosevelt would have agreed with his position, not Truman’s. This was the final straw. Wallace wasn’t just as green with policy. He was invoking Roosevelt’s name to undermine Truman’s authority.

He was suggesting that Truman had betrayed Roosevelt’s legacy. On September 20th, 1946, Truman called Wallace to the White House. The conversation was brief. Truman told Wallace he needed a cabinet that spoke with one voice on foreign policy. Wallace could either stop making public statements contradicting administration policy or resign.

Wallace chose to fight. He told Truman he had a constitutional right to free speech. He said the American people needed to hear alternative views on foreign policy. He argued that Truman was betraying Roosevelt’s vision of cooperation with the Soviets. Truman ended the meeting. He returned to his office and dictated a letter accepting Wallace’s resignation.

Wallace hadn’t offered to resign. Truman was firing him. The letter was delivered to Wallace that afternoon. Wallace was stunned. He had expected Truman to back down. He thought Truman needed him to maintain support from Roosevelt liberals. He believed his political base gave him leverage. Wallace had miscalculated completely.

Truman was willing to lose Wallace’s supporters rather than tolerate a cabinet member who publicly contradicted foreign policy. Party unity mattered less than policy coherence. Wallace sat in his office after being fired and realized he was free. Free from cabinet discipline. Free from administration loyalty.

free to say exactly what he thought about Truman’s policies, he called a press conference for the next day. Instead of issuing a gracious statement about moving on, Wallace announced he was dedicating himself to changing American foreign policy. He said Truman was leading America toward permanent confrontation with the Soviet Union.

Political analysts said Wallace had destroyed his political career. Wallace didn’t care. He believed stopping Truman’s foreign policy was more important than his own political future. From October 1946 through 1948, Wallace delivered hundreds of speeches to packed venues across America, offering warweary citizens a dangerous hope that conflict with Stalin was a choice, not a necessity.

The media coverage was massive. His criticisms of Truman reached millions of Americans. He became the most prominent voice opposing containment. Truman’s advisers were worried. Wallace’s message resonated with warweary Americans. Polls showed significant portions of the Democratic base questioned Truman’s tough stance on the Soviets.

Wallace wasn’t strong enough to win elections, but he was strong enough to split the Democratic Party. The content of Wallace’s speeches grew more extreme over time. In early 1947, he began arguing that Truman’s policy was actually causing Soviet aggression. He claimed that if America would just disarm and show good faith, Stalin would reciprocate.

He suggested the Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe was America’s fault for being confrontational. These arguments horrified foreign policy experts. They pointed out that Stalin had broken agreements made at Yaltta before Truman had even adopted a tough stance. Soviet expansion was happening regardless of American policy.

Wallace was blaming the victim. But Wallace’s supporters didn’t care about expert analysis. They cared about avoiding war. And Wallace was the only prominent political figure telling them war could be avoided. In early 1947, American intelligence agencies noticed something disturbing. Soviet propaganda was quoting Henry Wallace extensively.

Radio Moscow broadcast his speeches. Soviet newspapers reprinted his articles. Wallace’s criticisms of Truman were being used to undermine American foreign policy. Wallace didn’t see this as a problem. He argued that Soviet media quoted him because he was telling the truth. If Stalin’s government found his message useful, that was because his message was correct.

The real issue was Truman’s aggressive policy, not Soviet propaganda. But the intelligence community saw something more troubling. Wallace was receiving assistance from organizations with Soviet connections. The groups organizing his speaking tours had ties to communist parties. His staff included people who had worked with Soviet front organizations.

Wallace might be sincere in his beliefs, but he was being used by Moscow. In March 1947, Truman delivered a speech to Congress announcing what would become known as the Truman Doctrine. He requested funding to support Greece and Turkey against communist insurgencies. He declared that America would support free peoples resisting subjugation by armed minorities or outside pressures.

Wallace’s response was immediate and scathing. He called the Truman doctrine a declaration of war on the Soviet Union. He argued Truman was establishing an American empire. He claimed the president was betraying the United Nations and Roosevelt’s vision of collective security. The attack resonated with Wallace’s base, but horrified mainstream Democrats.

Even liberals who questioned containment thought Wallace had gone too far. Supporting Greece and Turkey wasn’t wararmongering. It was preventing Soviet expansion through strategic assistance. Wallace didn’t moderate his message. In June 1947, Secretary of State George Marshall announced the European Recovery Program to rebuild Western Europe.

Wallace denounced it as economic imperialism, designed to encircle the Soviet Union. The Marshall plan was enormously popular with the American public and European governments. Wallace’s opposition made him look increasingly isolated and extreme, but he pressed on, convinced he was preventing catastrophic conflict between superpowers.

In December 1947, Henry Wallace announced he was running for president. He would lead a new progressive party dedicated to peace and cooperation with the Soviet Union. The announcement shocked the political establishment. Wallace knew he couldn’t win. Third party candidates never won presidential elections, but he believed he could force Truman to change course on foreign policy.

If Wallace drew enough votes away from Truman, the president would have to moderate his stance on the Soviets to win re-election. The Progressive Party platform called for immediate negotiations with Stalin, withdrawal of American troops from Europe, sharing atomic weapons technology with the United Nations, including the Soviet Union, dismantling American military bases abroad, ending economic assistance tied to anti-communist conditions.

It was everything Moscow wanted. Soviet media celebrated Wallace’s candidacy. Communist parties in Europe endorsed him. Wallace accepted their support, arguing that anyone who wanted peace should be welcome in his coalition. This was politically catastrophic. Wallace’s association with communists allowed Truman to paint him as a Soviet dupe or worse.

Liberal Democrats who might have supported Wallace’s message refused to join a campaign tainted by communist connections. Wallace campaigned across America in early 1948. His rallies drew thousands. His message of peace resonated with voters tired of international tensions. Polls showed him drawing 10 to 15% of the vote. Almost entirely from Democrats who would otherwise support Truman.

Democratic party leaders panicked. If Wallace pulled that many votes, Truman would lose to Republican Thomas Dwey. The White House would flip to Republican control. Democrats would lose Congress. Everything Roosevelt had built would be dismantled. Truman’s political adviserss begged him to moderate his foreign policy to win back Wallace supporters.

Truman refused. He wasn’t going to change American strategic policy to win an election. The Soviets were expanding. Containment was necessary. Wallace’s supporters would have to choose between idealism and reality. By summer 1948, political analysts were predicting Truman’s defeat. The Democratic Party was fracturing.

Wallace was pulling liberal votes. Southern Democrats had bolted over civil rights to form the Dixierat party. Thomas Dwey was running a strong Republican campaign. Every poll showed Truman losing. Newsweek surveyed 50 top political writers. All 50 predicted Dwey would win. The Chicago Daily Tribune prepared a victory headline for Dwey before the votes were counted.

Truman’s presidency appeared finished. Wallace didn’t need to win. He just needed to make Truman lose. By siphoning liberal votes in New York, Michigan, and Maryland, he was handing key states to the Republicans. Then something changed in the final months of the campaign. Events in Europe vindicated Truman’s policy and exposed Wallace’s naivity.

In February 1948, communists staged a coup in Czechoslovakia, overthrowing the democratic government. The Soviet Union blocked all ground access to West Berlin in June, forcing the Berlin Airlift. These events demonstrated exactly what Truman had been warning about. Stalin wasn’t interested in cooperation or free elections.

Soviet expansion was real and aggressive. Wallace’s arguments about Stalin’s defensive intentions looked absurd. American voters shifted. Wallace’s poll numbers dropped from 10 to 15% down to 5%. Liberals who had been tempted by his peace message decided containment was necessary. Warweerary Americans realized that cooperation with Stalin wasn’t possible.

On election day, Wallace received only 2.4% of the national vote. He won no electoral votes. His campaign succeeded only in demonstrating how wrong he had been about Soviet intentions. Truman won re-election in one of the greatest upsets in American political history. Walls’s two-year campaign to destroy Truman’s presidency had failed completely.

Worse, it [snorts] had discredited the very position he was advocating. His association with Soviet propaganda had made opposition to containment politically toxic. On June 25th, 1950, North Korean forces invaded South Korea with Soviet weapons and Stalin’s approval. The attack was unprovoked and clearly coordinated with Moscow.

It proved everything Truman had argued about Soviet intentions. If America had followed Wallace’s advice and withdrawn from Asia, South Korea would have fallen in weeks. If America had shared atomic weapons technology with the United Nations, as Wallace proposed, the Soviets would have had nuclear weapons years earlier. If America had dismantled its military, as Wallace recommended, the entire Korean Peninsula would be communist.

The Korean War destroyed what remained of Wallace’s credibility. Stalin had proven he would use military force to expand communist control. Cooperation and trust were irrelevant to Soviet strategy. Containment was the only policy that worked. Wallace issued a statement supporting Truman’s decision to defend South Korea.

It was a quiet admission that he had been wrong about everything. Stalin couldn’t be trusted. Soviet expansion was aggressive, not defensive. military strength and alliances were necessary. By 1952, Wallace had retreated from public life. He wrote occasional articles, but never again challenged American foreign policy.

He had spent two years trying to destroy Truman’s presidency and ended up destroying his own legacy instead. In 1952, Henry Wallace published an article in This Week magazine titled Where I Was Wrong. It was the closest he ever came to a full apology. He admitted he had been naive about Soviet intentions. He acknowledged that some organizations supporting his 1948 campaign had been controlled by communists.

He conceded that containment had been necessary, but Wallace never admitted the fundamental mistake. He had been so convinced Truman was wrong that he spent two years trying to destroy a president who was actually right. He had given speeches that Soviet propaganda used to undermine American policy. He had run a campaign that nearly cost Truman reelection at a critical moment in the Cold War.

He died in 1965 largely forgotten by American politics. Former supporters had quietly distanced themselves. Liberal intellectuals who once cheered his speeches admitted they had been wrong. His name became associated with naive appeasement. Obituaries noted his service as vice president and his achievements in agriculture.

Most glossed over his two-year campaign against Truman. Henry Wallace spent two years trying to destroy Harry Truman’s presidency because he believed Truman was wrong about the Soviet Union. History proved Wallace was the one who was wrong. His tragedy wasn’t a lack of patriotism. It was a surplus of hope. He looked at Stalin and saw a partner because the alternative was too terrifying to accept.

In the end, conviction proved no substitute for judgment. And being Roosevelt’s vice president didn’t make someone qualified to be Roosevelt’s successor.

News

Steve Harvey WALKS OFF After Grandmother Reveals What Her Husband Confessed on His Deathbed

Steve Harvey had hosted Family Feud for over 16 years. And throughout that remarkable tenure, he had become known not…

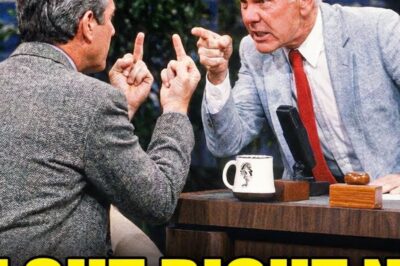

Johnny Carson Reveals 9 “Bastard” Guests He Banned for Life

In Hollywood, there is an unwritten law of survival that every star must engrave in their mind. ] You can…

Steve Harvey KICKED OUT Arrogant Lawyer After He Mocked Single Mom on Stage

Steve Harvey kicked out arrogant lawyer, a story of dignity and respect. Before we begin this powerful story about standing…

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Grandmother’s Answer Made Everyone CRY

Steve Harvey asked a simple family feud question to a 78-year-old grandmother, but her answer was so heartbreaking that it…

Steve Harvey STOPS Family Feud When Contestant Reveals TRAGIC Secret – What Happened Next SHOCKED

Steve Harvey asked a simple family feud question that should have been easy to answer. But when one contestant gave…

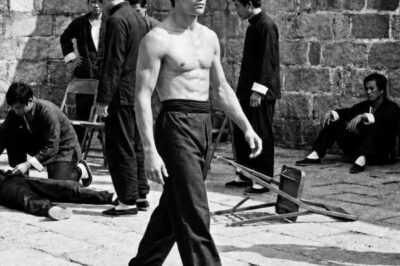

Bruce Lee’s unbelievable moment — if it hadn’t been filmed, no one would have believed it

Hong Kong, 1967. In the dimly lit corridors of a film studio. Bruce Lee, perhaps the greatest martial artist in…

End of content

No more pages to load