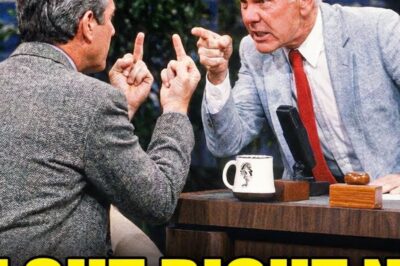

June 1942, Monttok Point, Long Island, New York. Dawn breaks over the Atlantic. A young Coast Guard technician flips a switch inside a weathered building. At that exact moment, 140 mi south at Fenwick Island, Delaware, another technician watches an oscilloscope screen, waiting. A sharp pulse of radio energy traveling at 186,000 m per second reaches his station in less than one millisecond.

He responds by transmitting his own pulse. These experimental transmissions would be refined and tested throughout the summer. By October 16th, 1942, the system would be declared operational, marking the birth of a weapon that would help win World War II. Not a bomb, not a gun. A navigation system so revolutionary that it would guide over 75,000 Allied ships and aircraft across oceans with an accuracy that would have seemed like magic just months earlier.

Here’s the contradiction that baffled Axis intelligence. Allied convoys were navigating across featureless oceans thousands of miles from land, hitting precise coordinates in total darkness and thick fog. No stars, no landmarks, no satellites wouldn’t exist for another 15 years. Yet somehow navigators were plotting positions accurate to within a few miles at ranges exceeding 1,400 m from shore.

The secret? Lauren, long range navigation. A system that used nothing more than precisely timed radio pulses and some brilliant mathematics to solve one of warfare’s oldest problems. Knowing exactly where you are when there’s nothing around you but water and sky. But the real story isn’t just about the technology.

It’s about the impossible engineering challenges that had to be solved to make it work. How do you synchronize radio stations separated by hundreds of miles to within micros secondsonds without any direct connection? How do you train thousands of operators to extract navigational data from ghostly signals bouncing off the ionosphere? How do you build 72 stations across the globe in the middle of a war? This is the story of how they did it. The year is 1940.

The Battle of the Atlantic is beginning and Allied ships face a lethal navigation crisis. Traditional navigation methods are failing spectacularly. Dead reckoning, compass heading, and estimated speed is accurate for maybe an hour or two before errors compound into dangerous guesswork. Celestial navigation requires clear skies and trained navigators taking seextant readings of stars.

But the North Atlantic is notorious for weeks of solid cloud cover. Radio direction finders exist, but they’re short range, easily jammed, and give only a bearing, not a distance. The mathematics is brutal. A convoy moving at 10 knots can travel 240 m in a day. If your navigation error is just 5° after 24 hours, you could be 21 m off course in the vast Atlantic.

That’s the difference between reaching port and sailing past it into a yubot wolfpack. Captain Harding of the US Navy laid out the requirement to the microwave committee at MIT’s newly formed radiation laboratory. We need accuracy of at least 1,000 ft at 200 m range with a maximum range of 300 to 500 m for high-flying aircraft.

But here’s what made this problem seemingly impossible. You can’t put an accurate clock on every ship. Crystal oscillators capable of microssecond precision in 1940 weighed hundreds of pounds, required constant calibration, and cost more than the ship itself. Any system that required ships to carry synchronized clocks was dead on arrival.

The breakthrough came from a wealthy physicist named Alfred Lee Lumis. Lumis had his own private laboratory at Tuxedo Park, New York, where he had been experimenting with precision timing for years. His fascination with measuring time to millionths of a second would unlock the solution. In 1959, he would be awarded the patent for the Lauran system.

Lumis proposed something radical, hyperbolic navigation. The concept is elegant. If two radio stations transmit pulses at precisely known times, a receiver can measure the difference in arrival times, that time difference defines a hyperbolic curve. All points where the distance difference from the two stations is constant.

Get two such measurements from two pairs of stations and the intersection of those curves gives you your exact position. No onboard clocks needed, no celestial observations, no dead reckoning guesswork, just pure mathematics and radio waves. But turning this theory into a working system would require solving problems no one had ever tackled before.

Challenge one, synchronization without connection. The master station at Montalk Point fires a radio pulse. Exactly 1 millisecond later, the slave station at Finwick Island must fire its own pulse. Not approximately, not roughly, exactly. 1 millisecond equals 1,000 microsconds. Radio waves travel 186 m per microscond. If your timing is off by just 10 micros, the position error is nearly 2 m.

At maximum range, that error multiplies catastrophically. How do you synchronize two stations 140 miles apart to microssecond precision? You can’t use phone lines. The signal delay is inconsistent. You can’t use radio signals from a third source. Those signals would arrive at different times at each station.

The solution was brilliantly simple. The slave station listens for the master. When the master’s pulse arrives after exactly 1 millisecond of travel time, the slave knows it’s been 1 millisecond since transmission. The slave adds a fixed delay to account for its own receiver electronics, then fires its pulse. The system synchronizes itself through the radio waves it’s measuring.

But this created another problem. Those radio waves don’t travel in straight lines. Challenge two, skywave chaos. During the day, Lauren worked reasonably well using ground waves, radio signals that follow Earth’s surface, clean, predictable, accurate to about 500 to 700 nautical miles. But at night, the ionosphere came alive.

That electrically charged layer 50 to 200 miles above Earth reflects radio frequencies like a mirror. Suddenly, a single transmitted pulse might bounce once, twice, three times off the ionosphere before reaching your receiver. Each bounce arrives at a slightly different time. A Lauran operator looking at their oscilloscope screen at night might see 30 different signal reflections from a single transmitter.

Some had bounced once off the E layer of the ionosphere. Others bounced twice. Some went up to the F layer. The display became a confusing forest of spikes overlapping and interfering. Which spike do you measure? The first arrival is the ground wave, but it’s weak and hard to see at long range. The strongest signal might be a three hop skywave, but its timing varies with atmospheric conditions.

Measure the wrong spike, and your position error could be 50 m or more. The solution required a combination of technology and human skill. Engineers designed displays that could show signal patterns at different time scales. Operators were trained exhaustively to recognize signal signatures to distinguish a clean ground wave from skywave reflections to identify which bounce pattern they were seeing. It was part science, part art.

Experienced Lauran operators developed an almost intuitive sense for reading the patterns. They could glance at a screen and say, “That’s a two hop E-layer reflection. Ignore it. That small spike is your ground wave. Use that one. Challenge three, the display problem. British G Navigation used a cathode ray tube display, basically an early oscilloscope.

The American team initially tried to copy this approach. It failed spectacularly. [snorts] G worked in higher frequencies with shorter, sharper pulses. Lauran operated at 1.85 85 to 1.95 MHz, much lower frequencies where pulses spread out in time like smeared ink. Measuring the exact start of a smeared pulse on a CRT screen was like trying to determine the exact edge of a shadow.

The Lauran team needed multiple measurement scales. First, a wide view to identify which signals belong to which stations. then progressively zoomed views to make precise measurements. They developed an ingenious sevenstage sweep system. At sweep speed one, the operator saw all stations in the area, identifying their target pair by pulse repetition rate.

Speeds two and three progressively zoomed into the selected signals. Speed four overlaid them for comparison. Speeds 5, 6, and 7 added electronic timing scales with pips representing 10, 50, and 500 microscond intervals. The operator added up measurements from all three scales to get total time delay accurate to about 1 microcond.

Taking a single position fix required 3 to 5 minutes of concentrated work. The navigator would measure one station pair, plot that hyperbolic line on a chart covered with preprinted curves, then repeat the entire process with a different station pair. Only then could they mark their position at the intersection.

3 to 5 minutes doesn’t sound long until you realize the aircraft or ship is moving the entire time. The navigator had to account for that movement in their calculations. dead reckoning on top of Lauran measurements. The Monttok breakthrough. By early 1942, the radiation laboratory had a working prototype.

They chose two abandoned Coast Guard stations. Montalk Point on the eastern tip of Long Island and Thenwick Island on the Delaware coast. A station wagon fitted with a receiver drove throughout the northeastern United States testing signal range. To everyone’s astonishment, they picked up solid signals as far inland as Springfield, Missouri, over 1,000 m away.

The lower frequencies were working even better than predicted. But going from prototype to operational system meant solving hundreds of practical problems. Each Lauran station required a transmitter capable of generating pulses with extremely fast rise times. The sharper the pulse edge, the more accurately you could measure it. Engineers customuilt high power vacuum tube transmitters operating at 100 kow each.

These weren’t off-the-shelf components. Every transmitter was handtuned. Antenna systems presented their own challenge. At frequencies around 1850 to 1950 kHz, the ideal antenna is about 260 ft tall. But these stations often had to be built in remote coastal locations where construction materials and crews were scarce.

Many used towers supported by cables, requiring careful engineering to prevent signal distortion from the support structure itself. Timing systems at each station used crystal oscillators, the most accurate timekeepers available in 1942. But even the best crystals drift. Engineers developed elaborate calibration procedures.

Every station received standard time signals from WWV, the National Bureau of Standards radio station, and operators manually compared and adjusted their timing daily. The human element, negotiating the impossible. Not all challenges were technical. Building a chain of stations along the Canadian coast required negotiating with land owners and dealing with local politics.

One site in Nova Scotia proved particularly difficult. The property was owned by a fisherman whose wife was a strict tea totler and wanted nothing to do with sinful Navy men. The site selection committee, JA Wald Schmidt and Lieutenant Commander Argyle, were in negotiations when a third visitor arrived and offered everyone cigarettes. Wald Schmidt and Argyle refused.

The hostess asked if they drank. They said no. The land was secured immediately. Global deployment 72 stations in three years. By October 16th, 1942, the first Lauran chain was declared operational along the US East Coast, initially running 16 hours per day. Monttok, Fenwick, Cape Bonavista, and Battle Harbor in Newfoundland and Bicaro and Deming Island in Nova Scotia.

By June 1943, service expanded to 24 hours daily. Then came the sprint. The Coast Guard formed engineering battalions trained in rapid station construction. They deployed to some of the most remote and hostile environments on Earth. Greenland stations had to be built on perafrost where standard construction techniques failed.

Engineers developed special foundation designs that wouldn’t shift as ground froze and thawed. Supply ships could only reach some locations during brief summer windows, meaning a year’s worth of fuel, food, and spare parts had to be delivered in weeks. Iceland, Pharaoh Islands, the Hebdes, chains spread across the North Atlantic.

Each required its own supply line, its own maintenance crew, its own contingency plans. RAF Coastal Command installed a station in the Shetland Islands, providing coverage over Norway’s coast, where German hubot and capital ships staged operations. In the Pacific, distances were even staggering.

Island chains across thousands of miles of ocean. Some stations were built on tiny atalls barely above sea level where saltwater corrosion destroyed equipment in months. Supply lines stretched from Hawaii to the Philippines requiring coordination with island hopping military campaigns. By the end of 1945, 72 Lauran stations blanketed the globe.

Coverage extended over 30% of Earth’s surface, primarily the northern hemisphere. Over 75,000 receivers were in operation on ships and aircraft. The receiver evolution. Early Lauren receivers were massive. The APN4 airborne unit introduced in 1943 consisted of two separate boxes each about 1 ft by 2 ft.

The display unit, the indicator, weighed 45 lbs. It required a trained operator sitting at a dedicated navigation station, often under a leather hood to block ambient light while reading the dim cathode ray tube. British engineer Robert Dippy, lead developer of the G system, was sent to America for 8 months in mid 1942 to assist Lauran development.

He made one brilliant design decision. The ANPN4 was built to exactly match the dimensions of British G receivers. Aircraft could swap between the two systems in minutes just by replacing the receiver unit. This proved crucial for RAF transport command. Aircraft flying to Australia could use G over Europe, Lauran over the Atlantic and Pacific.

one aircraft, multiple navigation systems, seamless transitions. By 1945, the ANPN9 replaced the ANAPN4, an all-in-one unit combining receiver and display in a single package, significantly lighter and more reliable. But even this unit required intensive operator training. The training program became its own massive undertaking.

Thousands of navigators needed to learn not just how to operate the equipment, but how to interpret complex signal patterns, how to account for ionospheric propagation, how to plot hyperbolic lines on specialized charts, and how to troubleshoot when signals weren’t cooperating. Accuracy in practice. Theoretical accuracy is one thing.

Realworld performance is another. On the route from Japan to Tinian Island, a critical 1,400 mile supply run, measurements showed average errors of just five miles at maximum range in operational conditions with operators working in cramped vibrating aircraft or rolling ships. This was revolutionary. Pre-Luran navigation at those distances might accumulate errors of 50 to 100 m.

Luran reduced that by a factor of 10 to 20. For bombers on long range missions, Luran meant they could reduce safety margins. Instead of carrying extra fuel for an hour of searching for their home base, they could cut fuel reserves and carry more bombs. Strike planning became more aggressive because planners trusted aircraft could find their targets and return precisely.

The Pacific theater revealed Luran’s true power. vast empty ocean, islands scattered across thousands of miles, few landmarks. Before Luran, finding a tiny atal after a 1500-mile flight was equal parts skill and luck. With Luran, it became routine. Battle of the Atlantic. In the North Atlantic, convoys used Luran to follow optimized routes that avoided known yubot positions.

Navigation accuracy meant convoys could spread out slightly, making harder targets while still maintaining precise formations for mutual defense. When a hubot was spotted, escorts could vector to exact locations using Luran coordinates, arriving faster and more accurately than ever before. German intelligence knew the Allies had some sort of advanced navigation system.

They could observe that Allied aircraft were hitting precise coordinates in conditions that should have made navigation impossible, but they couldn’t figure out how it worked. Lauran stations transmitted in all directions. There was no narrow beam to trace back to a source. The signals themselves revealed nothing about the systems operating principles.

Skywave synchronized Lauren, pushing the limits. Jack Pierce, one of the radiation lab engineers, noticed something fascinating. The ionosphere’s reflective properties, while variable, weren’t random. At night, the layers stabilized somewhat. Skilled operators could use skywave signals for measurements, not just as interference to avoid.

This led to experiments with skywave synchronized Lauran or SS Lauran. Instead of spacing stations 300 to 400 m apart for groundwave coverage, what if you spaced them,00 m apart and used skywave reflections intentionally? Tests between Fenwick and Bonav Vista, 1100 m distant, demonstrated accuracy of better than 1/2 mile.

This was extraordinary. Four test stations were dismantled, shipped to Europe and reinstalled. Aberdine, Bazerta, and Oran, Benghazi. SS Lauran covered everything south of Scotland and east to Poland. RAF Bomber Command adopted it enthusiastically. By October 1944, it was operational. By 1945, number five group RAF used it universally for nighttime bombing runs over Germany.

The accuracy improvement came with a trade-off. SS Lauran only worked at night when ionospheric conditions were right. Operators needed even more training to interpret skywave patterns correctly. But for strategic bombing missions that occurred at night anyway, it was perfect. Lauran C, the next generation. The original Lauran, later designated Lauran A, used pulse envelope timing.

You measured the time between the leading edges of radio pulses. This technique has fundamental accuracy limits. Engineers proposed a better method, phase comparison. Instead of measuring when the pulse arrives, measure the phase of the carrier wave within the pulse. Radio waves at 100 kHz have a cycle every 10 microsconds.

By measuring which part of the wave cycle you’re seeing, accuracy jumps dramatically. The challenge was distinguishing between one cycle and the next, the lane ambiguity problem. The solution combined both techniques. Rough envelope timing to identify which lane you’re in. Then precise phase measurement for exact position within that lane.

This became Lauran C operating at 100 kHz. Experiments in 1945 with low frequency Lauran demonstrated remarkable accuracy using cycle matching techniques. 150 ft at 750 mi under optimal conditions. When Luran C became fully operational in 1957, it provided repeatable accuracy of 60 to 300 ft, 18 to 91 m with absolute accuracy of 0.1 to 0.

25 nautical miles, 185 to 463 m. Lauran C required far more complex receivers. Early versions filled entire equipment racks, but by the late 1950s, transistors made compact units practical. The system was declared operational in 1957, and the US Coast Guard took over operations in 1958. Lauran A remained in service longer than anyone expected.

Even though Lauran C was more accurate, Lauran A receivers were simpler and crucially thousands of surplus military units flooded the commercial market after World War II ended. Fishing fleets snapped them up. Commercial ships installed them. By the 1970s, micro electronics made Lauran A receivers cheap enough for small boats. The system remained operational in North America until 1980 with some foreign chains running into the 1990s.

A Chinese system was still active in 2000. Lauran C thrived from the 1960s through 2010. At its peak, the North American Lauran Sea system consisted of 29 stations organized into 10 chains, providing coverage across the United States, coastal waters, and far out into the Atlantic and Pacific. For mariners, Lauren C became the standard accuracy of 0.1 to.

25 nautical miles anywhere within coverage areas. Simple digital receivers that display latitude and longitude directly. No operator training required. Punch in a waypoint and go. Then came GPS. The US Coast Guard shut down American Lauran Sea signals on February 8th, 2010. GPS satellites provided better accuracy, global coverage, and cheaper receivers.

The era of land-based radio navigation appeared to be over. But here’s the twist. In 2025, there’s renewed interest in Lauren technology. Why? Because GPS is vulnerable. GPS signals are incredibly weak by the time they reach Earth. A GPS satellite orbits 12,500 m up, transmitting with about 50 watts of power.

At ground level, the signal is roughly one quadrillionth of a watt. You can jam GPS with a cheap handheld transmitter. You can spoof it, feeding false signals that move your apparent position miles away. Military exercises have demonstrated that in a contested environment, GPS can be denied over wide areas.

Lauran signals, by contrast, are massively powerful. Groundbased transmitters pumping out 100,000 to 1 million watts. Those signals are extraordinarily difficult to jam without equally powerful transmitters which are large, expensive, and easy to locate and destroy. Enhanced Lauren or Eloruran updates the technology with modern digital signal processing.

Accuracy competitive with GPS 8 to 20 m in many locations. Works indoors where GPS fails. immune to space weather that can disrupt satellites. Provides an independent backup for critical infrastructure. Power grids, telecommunications, financial networks all depend on precise timing that GPS provides. If GPS goes down, modern society faces cascading failures.

Several nations are exploring euran deployment. Russia maintains their Chica system, essentially their version of Lauran C. South Korea built euran stations. European nations are evaluating it. The technology that won World War II might help protect 21st century infrastructure. The enduring lessons.

Lauran succeeded because it solved the right problem in the right way. Instead of demanding that ships carry expensive complex equipment, it put the complexity in a few dozen ground stations. Instead of fighting against radio propagation physics, it embraced them, turning ionospheric reflections from liability into capability.

The engineers who built Lauran understood that perfect accuracy wasn’t necessary. 5m accuracy at 1,400 m range was enough to win the war. They optimized for good enough and deployable rather than theoretically perfect but impractical. And they built it fast. From initial concept in October 1940 to first operational chain in October 1942.

That’s 24 months. From prototype to 72 stations covering 30% of the globe by 1945. That’s 5 years during wartime with supply chain chaos and resource scarcity. Two radio stations. Precisely timed pulses. Simple mathematics. That’s all Lauran needed to guide 75,000 Allied ships and aircraft across the world’s oceans with accuracy that seemed impossible.

No satellites, no GPS constellation costing tens of billions of dollars. Just towers, transmitters, and brilliant engineering solving an impossible problem under wartime pressure. The next time you check Google Maps or let your phone navigate you somewhere, remember your satellitebased GPS system is descended from engineers who figured out how to do something similar 85 years ago using 1940s technology.

They worked with vacuum tubes, handculated hyperbolic curves, and cathode ray tubes that weighed 45 lb. and they made it work well enough to change the outcome of the largest war in human history. If you found this story fascinating, subscribe for more deep dives into the ingenious engineering that shaped warfare.

Next episode, we’re exploring another impossible communication system. The Cold War era submarine cables that carried secret messages 3,000 ft below the Atlantic, tapping Soviet communications without the Russians ever knowing. Hit that subscribe button, click the bell for notifications, and drop a comment. What other World War II navigation secrets should we uncover? Thanks for watching.

Until next time, keep exploring how brilliant engineering solves impossible problems.

News

Steve Harvey WALKS OFF After Grandmother Reveals What Her Husband Confessed on His Deathbed

Steve Harvey had hosted Family Feud for over 16 years. And throughout that remarkable tenure, he had become known not…

Johnny Carson Reveals 9 “Bastard” Guests He Banned for Life

In Hollywood, there is an unwritten law of survival that every star must engrave in their mind. ] You can…

Steve Harvey KICKED OUT Arrogant Lawyer After He Mocked Single Mom on Stage

Steve Harvey kicked out arrogant lawyer, a story of dignity and respect. Before we begin this powerful story about standing…

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Grandmother’s Answer Made Everyone CRY

Steve Harvey asked a simple family feud question to a 78-year-old grandmother, but her answer was so heartbreaking that it…

Steve Harvey STOPS Family Feud When Contestant Reveals TRAGIC Secret – What Happened Next SHOCKED

Steve Harvey asked a simple family feud question that should have been easy to answer. But when one contestant gave…

Bruce Lee’s unbelievable moment — if it hadn’t been filmed, no one would have believed it

Hong Kong, 1967. In the dimly lit corridors of a film studio. Bruce Lee, perhaps the greatest martial artist in…

End of content

No more pages to load