September 20th, 1941, 23,000 ft above the Bisque coast of France, squadron leader Rupert Clark’s hands rested steady on the control column of his dehavlin mosquito as three Messesmmit 109s climbed desperately toward him through the crisp morning air. The German pilots, veterans of two years of continuous combat, expected an easy kill.

The twin engine aircraft above them appeared to be a reconnaissance plane, probably a slow Bristol Blenhim or perhaps a lost bow fighter. Either way, it was meat for their cannon. What they didn’t know, what they couldn’t have imagined, was that they were chasing the future of aerial warfare, a machine that would make them question everything they thought they knew about speed, about interception, about the very possibility of stopping an enemy aircraft.

Clark watched the 109s in his mirror. They were climbing hard, engines screaming at maximum power, closing the distance slowly. Too slowly. When they reached 23,000 ft and lined up for their attack, Clark simply pushed the throttles forward. The two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines responded with a smooth surge of power.

The Mosquito accelerated effortlessly and pulled away from the German fighters as if they were standing still. The 109 pilots watched in disbelief as their target simply disappeared into the distance. They were flying the best fighter in the Luftwaffer. They had experience. They had altitude advantage and they couldn’t even get within firing range.

That morning, the Luftwaffer learned a truth that would haunt them for the rest of the war. There was an aircraft in the sky that they could not catch. September 20th, 1941 marked the first operational sorty of the dehavlin mosquito and it would not be the last time German pilots watched helplessly as the wooden wonder flew beyond their reach.

This is the story of how a machine built from plywood and balsa wood, dismissed by experts as obsolete before it even flew, became the aircraft that the head of the Luftwaffer himself admitted made him green with envy. This is the story of the day the Luftwaffer met the mosquito and realized they couldn’t catch it.

The mosquito was born from desperation and rejected by tradition. In September 1939, as German forces rolled across Poland and Europe, braced for war, Jeffrey De Havland, the 57-year-old founder of De Havland Aircraft Company, sat in his office at Hatfield Aerad Drrome with an idea that seemed completely insane.

He wanted to build a bomber with no defensive guns. In 1939, this was aviation heresy. The entire philosophy of bomber design centered on defensive firepower. The Boeing B7 bristled with machine guns. The short sterling carried turrets for and after. The accepted wisdom was simple. Bombers needed guns to fight their way to the target and back.

De Havlin proposed the exact opposite. Build a bomber so fast that fighters couldn’t catch it. Make it from wood, a non-strategic material that wouldn’t compete with aluminum production for fighters. Use the weight saved from guns, gunners, ammunition, and turrets to carry bombs and fuel. Keep it small, keep it fast, and let speed be the only defense.

He wrote to Air Marshal Sir Wilfried Freeman on September 20th, 1939, outlining his concept for a high-speed unarmed bomber constructed from non-strategic materials that could fly faster than current fighters in service. The proposal landed on desks throughout the Air Ministry where it was promptly rejected by almost everyone who read it.

Air Chief Marshall Sir Hugh Dowing called it a gamble. The director of technical development said it was fundamentally unsound. Test pilots said no bomber could outrun a fighter. Production experts said wooden aircraft were obsolete. Even within De Havlin’s own company, some engineers thought their boss had lost his mind. But Freeman believed in it.

Against the advice of nearly every expert in the air ministry, he pushed the project forward. In December 1939, the Air Ministry reluctantly approved a contract for 50 aircraft. They did so with little enthusiasm and considerable skepticism. What emerged from that contract was something that would change aerial warfare forever.

The design that took shape on De Havlin’s drawing boards was revolutionary in its simplicity and radical in its execution. The fuselage would be a monoke shell of birch plywood over a balsa wood core glued and screwed together like a piece of fine furniture. The wings would use spruce spars with plywood skins.

No rivets, no sheet metal, no conventional aircraft construction at all. The prototype designated W450 was built in total secrecy at Ssbury Hall, a small mana house near Hatfield. The bright yellow aircraft took to the air for the first time on November the 25th, 1940 with Jeffrey De Havlin Jr. at the controls. The takeoff was straightforward, the handling was pleasant, and when they pushed it to see what it could do, the results exceeded even the designer’s expectations.

On January 16th, 1941, during performance trials at RAF Boscom down, W4 Phospho 50 reached 388 mph at 22,000 ft. A Spitfire Mark 2 tested the same day managed 360 mph at 19,500 ft. The wooden bomber was faster than the RAF’s frontline fighter. Further testing pushed the prototype to 392 mph, and with refinements, it would go faster still.

The test pilots who flew it came back with the same report. It was extraordinarily pleasant to fly. The controls were light and responsive. Visibility was excellent. The two Merlin engines provided smooth, reliable power. It climbed well. It dove beautifully and it was fast, very fast. The Air Ministry, facing the reality of actual performance data, reversed their skepticism.

On June 21st, 1941, they authorized mass production. The order called for 19 photo reconnaissance models and 176 fighters. By January 1942, contracts had been awarded for 1,78 mosquitoes of all variants. The gamble that almost no one believed in had become one of the most important aircraft programs in the RAF. But orders and contracts meant nothing until the Mosquito proved itself in combat.

That proof would come gradually, mission by mission, as German pilots discovered that everything they thought they knew about interception was useless against this new British aircraft. The first PR mosquitoes entered service with number one photographic reconnaissance unit at RAF Benson in July 1941. These aircraft carried no bombs and no guns, just cameras and fuel.

Their defense was altitude and speed, nothing else. Squadron leader Clark’s encounter on September 20th set the pattern for what would follow. German fighters would detect the mosquito. They would climb to intercept. They would watch it fly away. In October 1941, three mosquitoes were detached to RF Wick in Scotland to perform reconnaissance flights over Norway.

The missions were deep penetrations into heavily defended airspace. The aircraft flew alone, without escort, without support. They relied entirely on their performance to survive, and they did. Flight after flight, the mosquitoes returned with photographs of German installations, ship movements, and coastal defenses. The Luftvafa scrambled fighters.

The flack batteries opened fire. The mosquitoes photographed their targets and flew home. By early 1942, German intelligence was compiling reports on a new British aircraft that seemed impossible to intercept. Fast, high-flying, wooden construction that made it difficult to track on radar. The reports were consistent and troubling.

Fighters couldn’t catch it. In February 1942, the bomber variants began operations. Number 105 squadron took delivery of the first mosquito B MarkVs and immediately began experimenting with low-level precision bombing. The concept was revolutionary. Instead of high alitude area bombing, the mosquitoes would go in low and fast, hitting specific targets with incredible accuracy.

On May 31st, 1942, four mosquitoes from 105 Squadron executed the first operational bombing mission, a daylight raid on Cologne. They flew at 50 ft across the North Sea, climbed to 1/500 ft over the target, dropped their bombs with precision, and returned home. All four aircraft made it back. The success led to more ambitious operations.

Throughout the summer and fall of 1942, Mosquito squadrons conducted precision raids across occupied Europe. They hit factories, railways, power stations, and Gustapo headquarters. They flew in daylight when weather permitted. They flew alone or in small formations and their loss rates were remarkably low. But it was a mission on January 30th, 1943 that would demonstrate the mosquito’s capabilities in the most public and humiliating way possible for the Luftwaffer.

January 30th, 1943 marked the 10th anniversary of Adolf Hitler’s rise to power. The Nazi party planned a day of celebration throughout the Reich. In Berlin, massive rallies were organized. Reich’s Marshall Herman Guring, commander of the Luftwafer, was scheduled to deliver a major speech at 11:00 a.m. to be broadcast live throughout Germany from the House Runfunks, the headquarters of the German state broadcasting company.

Later that afternoon, propaganda minister Yseph Gerbles would address thousands at the Shonberg Sport Palast, Berlin’s largest indoor arena. Both speeches would be broadcast live to boost German morale during what was becoming an increasingly difficult war. British intelligence knew all of this and they had an idea.

At precisely 11 RAM, as Guring prepared to speak, three mosquitoes from 105 squadron screamed over Berlin in broad daylight. At 25,000 ft, they emerged from the clouds into brilliant sunshine directly over the German capital. Air raid sirens wailed. Anti-aircraft batteries opened up and the sound of Merlin engines and exploding 500 pound bombs echoed across the city.

The radio engineers faced an impossible choice. They could broadcast the sound of British bombers attacking Berlin, or they could cut the transmission. They cut it. German listeners heard air raid sirens, then silence, then scratchy classical music. It was over an hour before a furious guring could finally deliver his speech.

The humiliation was complete. 3 hours later at precisely 4 p.m. three more mosquitoes from 139 squadron appeared over Berlin as Gerbles prepared to speak at the sport palast. This time the anti-aircraft defenses were at full alert. The flack was intense. The fighters were scrambling. One mosquito flown by squadron leader DFW Darling and flight officer Wright was shot down.

But the mission succeeded. British bombers had attacked Berlin twice in one day in broad daylight at precisely the times chosen to cause maximum propaganda damage and there was nothing the Luftvafer could do to stop them. Guring was beside himself with rage. Years earlier he’d publicly promised the German people that no enemy aircraft would ever fly over the Reich.

He had even said that if enemy bombers reached Germany they could call him Mer using a Jewish name as an insulting slur. Now British aircraft had struck Berlin twice in one day during the most important Nazi celebration of the year. All six mosquitoes that attacked that morning had returned safely. Of the six in the afternoon raid, five made it home.

The Luftwaffer had scrambled fighters. They had fired thousands of rounds of anti-aircraft ammunition and they had shot down one aircraft out of 12. The propaganda disaster was matched by the operational reality. The Luftvafer could not defend Berlin in daylight against mosquitoes. In March 1943, deep in his hunting lodge at Karenhole in the Shaw feeder forest, Guring summoned the technical heads of the German aviation industry.

The meeting lasted 6 hours. Stenographers recorded every word. At one point, Guring turned to face Professor Willie Messid and delivered what became one of the most famous quotes of the war. It makes me furious when I see the mosquito. I turn green and yellow with envy. The British, who can afford aluminum better than we can, knock together a beautiful wooden aircraft that every piano factory over there is building, and they give it a speed which they have now increased yet again.

What do you make of that? There is nothing the British do not have. They have the geniuses and we have the Ninkham poops. The quote spread throughout the Luftvafer. Pilots repeated it in bitter jest. Intelligence officers included it in reports. The head of the German Air Force had publicly admitted that the enemy had built a superior aircraft and Germany had no answer to it.

But the admission, honest as it was, didn’t explain why the mosquito was so difficult to intercept. Understanding that requires understanding the mathematics of pursuit. When a fighter attempts to intercept a bomber, several factors determine success or failure. The fighter must be vetoed to the target’s location.

It must have sufficient altitude advantage or must climb to the bomber’s altitude. It must close the distance and it must maintain that closure long enough to get within firing range. Every second matters. Every mile hour of speed differential matters. Against a bomber flying at 200 mph, a fighter flying at 350 mph has ample time to intercept.

The speed advantage of 150 mph means the fighter closes at 220 ft pers. From 5 m away, interception takes roughly 2 minutes. That’s manageable. Against a mosquito cruising at 300 mph at 25,000 ft, the same fighter flying at 350 mph closes at only 73 ft pers. From 5 m away, interception takes over 6 minutes. And that assumes the fighter is already at altitude, already in position, already on an intercept course.

If the mosquito detects the fighter and increases speed to 350 mph, the closure rate drops to zero. The fighter can’t catch up. It can only maintain distance. If the mosquito goes to maximum power and reaches 380 mph, it pulls away. The mathematics become impossible. The fighter falls behind at 44 ft pers.

In 2 minutes, the mosquito is a mile and a half farther away. The pursuit is over before it begins. This reality frustrated German pilots beyond measure. Obeloidant Ysef Priller, commanding officer of Yakashvada 26, one of the Luftvafa’s elite fighter units, encountered mosquitoes repeatedly throughout 1942 and 1943. His combat reports reflected growing frustration.

Visual contact made at 7,000 m. Attempted interception. Target increased speed, unable to close. Target disappeared into clouds. Another mission. Radar contact reported fastmoving bogey. Scrambled at maximum climb. Reached altitude. No contact. Target had already passed again. Detected reconnaissance aircraft over coast. Pursued at full throttle.

Target maintained distance. Ran low on fuel. Broke off pursuit. The pattern repeated across every Luftwaffer fighter unit on the Western Front. The reports filled filing cabinets. The conclusions were always the same. Cannot intercept. Target too fast. Lost contact. Return to base. But speed alone doesn’t explain the Mosquito success.

The aircraft had another advantage that drove German fighter pilots to distraction. It could operate at altitudes where German fighters struggled. The Rolls-Royce Merlin engine that powered the Mosquito used a two-stage two-speed supercharger. This system compressed intake air in two stages, allowing the engine to maintain sea level power output at altitudes where the air was thin.

A Mosquito Mark IV could cruise at 27,000 ft with full power available. A Messid 109F at 27,000 ft was struggling. The engine was gasping for air. Performance degraded significantly. Climb rate dropped. Acceleration suffered. Maximum speed fell. Even if a 109 pilot managed to position for an attack, his aircraft was operating at the edge of its performance envelope.

While the mosquito was flying comfortably well within its capabilities, the Fauler Wolf 190, introduced in 1941 as Germany’s answer to the Spitfire, was even worse at altitude. The BMW 801 radial engine used a single stage supercharger optimized for low to medium altitude performance. At 27,000 ft, a Fauler Wolf 190A was practically helpless.

The engine produced perhaps 60% of its rated power. The aircraft wallowed. Controls felt mushy. Any mosquito flying above 25,000 ft was effectively immune to 190s. The Luftvafer knew this. They attempted various solutions. They developed high altitude variants of the 109 with pressurized cockpits and improved superchargers.

They experimented with GM1 nitrous oxide injection systems to boost power at altitude. They created specialized highaltitude interception units equipped with the best available equipment. All of these efforts had marginal success at best. The specialized variants were produced in tiny numbers. The modifications were complex and unreliable.

The dedicated interception units scored occasional victories but couldn’t stop the steady stream of mosquito operations. Meanwhile, the RAF kept improving the mosquito. The Mark 9 bomber variant introduced in 1943 used more powerful Merlin 72 or 73 engines. Top speed increased to 408 mph. Service ceiling reached 37,000 ft.

The Mark1 16th reconnaissance variant with Merlin 72 or 76 engines could cruise at 415 mph at 30,000 ft. At those speeds and altitudes, interception wasn’t difficult. It was nearly impossible. German fighter pilots developed a grudging respect bordering on obsession for the British aircraft. Captured Luftwafa documents revealed the depth of their frustration.

A tactical assessment from Yagashwada 2 dated August 1943 was brutally honest. The mosquito reconnaissance and bomber variants present the most difficult interception problem in current operations. Speed and altitude capability exceed our fighter performance above 7,000 m. Radar detection provides insufficient warning time.

Visual detection often occurs after the target has passed. Pursuit is generally unsuccessful. The only effective interception opportunities occur when mosquitoes are detected during approach at low altitudes or when weather forces them below optimal operating height. These opportunities are rare. The report recommended assigning the newest fighters the most experienced pilots and the best radar controllers to mosquito interception.

It acknowledged that even with these advantages, success would be limited. But if speed and altitude made the mosquito difficult to intercept, its versatility made it impossible to counter systematically. The aircraft wasn’t designed for just one role. It could do everything. Bomber variants carried up to 4,000 lb of bombs, the same load as a Boeing B7 flying fortress in an aircraft a fraction of the size.

Fighter variants mounted four 20 mm Hispano cannon and 4303 caliber Browning machine guns in the nose, creating devastating firepower. Night fighter variants carried radar, turning them into deadly hunters of German bombers. Fighter bomber variants combined bombs and guns for precision ground attack. Reconnaissance variants carried multiple cameras for high altitude photo reconnaissance.

Coastal command variants carried depth charges and rockets for anti-ubmarine warfare. The Luftwaffer couldn’t predict what a mosquito would do or where it would appear. It might be photographing Berlin at 35,000 ft in the morning and bombing a factory in Hamburg at 100 ft that afternoon. It could mark targets for heavy bomber raids, intercept German night fighters, attack shipping in Norwegian fjords, or drop special operations teams behind enemy lines.

In late 1943, a new role emerged that would become one of the Mosquito’s most famous missions. The Pathfinder Force, an elite RAF unit responsible for marking targets for night bombing raids, began using mosquitoes extensively. The aircraft’s speed allowed it to reach targets ahead of the main bomber stream. Its accuracy allowed it to mark targets precisely.

Its survivability meant Pathfinder crews had a better chance of completing multiple missions. By 1944, mosquitoes were leading nearly every major RAF Knight bombing raid over Germany. They would arrive first, identify the target, drop colored marker flares, and guide the heavy bombers to the target. German night fighters tried desperately to shoot down the Pathfinders, knowing that without accurate marking, the bomber streams would be far less effective.

But catching a mosquito at night, flown by an experienced crew, was extraordinarily difficult. The aircraft’s wooden construction produced a smaller radar signature than metal aircraft. Its speed allowed it to outrun most night fighters, and its maneuverability, excellent for a twin engine aircraft, allowed it to evade attacks that would have destroyed a Lancaster or Halifax.

The statistics were remarkable. By war’s end, mosquito bombers would have the lowest loss rate of any RAF bomber command aircraft type. Less than 1% of sorties resulted in aircraft lost. For comparison, Lancaster bombers lost over 3% of sorties. Halifax bombers lost over 3 and a half%. The Mosquito’s combination of speed, altitude, and wooden construction made it nearly three times more survivable than heavy bombers.

But perhaps the mission that best demonstrated the mosquito’s unique capabilities occurred on February 18th, 1944. The target was Among Prison in Northern France. The mission would become known as Operation Jericho, and it would showcase everything the mosquito could do. By early 1944, the Gestapo’s winter offensive against the French resistance had filled Amian’s prison with hundreds of resistance fighters and political prisoners.

British intelligence learned that mass executions were planned. Among the prisoners scheduled to die were key resistance leaders whose knowledge of Allied invasion plans made them security risks. The decision was made to attempt a rescue through aerial bombardment. The plan was audacious to the point of insanity.

19 mosquito fighter bombers would fly to amiens in broad daylight. They would approach at ultra low level to avoid radar detection. They would climb to bombing altitude at the last moment. And they would drop bombs with surgical precision to breach the prison walls without destroying the prison itself. The first wave would breach the outer walls.

The second wave would destroy the guard’s barracks. A third wave would stand by in case additional strikes were needed. If executed perfectly, the prisoners would have minutes to escape before German troops could respond. If executed imperfectly, hundreds of prisoners would die under British bombs. The mission was assigned to 140 wing of the second tactical air force.

18 Mosquito Mark 6 fighter bombers, each carrying two 500lb bombs with delayed fuses, would make the attack. Six aircraft from 487 Squadron Royal New Zealand Air Force commanded by Wing Commander Irving Smith. Six from 464 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force commanded by Wing Commander Bob Ayardale.

Six from 21 Squadron Royal Air Force commanded by Wing Commander Iva Dale held in reserve. A 19th Mosquito from the Royal Australian Air Force Film Production Unit would accompany the raid with cameras to document the results. Leading the entire operation was group Captain Percy Charles Pickard, one of the most famous pilots in the RAF.

At 28 years old, Pickard held the Distinguished Service Order with two bars and the Distinguished Flying Cross. He had flown Wellingtons in the early years of the war. He had survived being shot down and ditching in the North Sea. He had become the public face of RAF bomber command through his appearance in the propaganda film Target for Tonight.

He was the ideal choice to lead the most difficult precision bombing mission of the war. On the morning of February 18th, the weather was appalling. Snow covered much of England and northern France. Visibility was poor. Winds were strong. The forecast called for marginal conditions at best.

But the intelligence indicated that executions could happen at any time. The mission could not be delayed. At 11 Helam, the mosquitoes took off from RAF Hunden in Hertfordshire. Four aircraft became separated in the weather and returned to base. One suffered engine problems and turned back. That left 13 mosquitoes to make the attack.

Nine in the first two waves, four in reserve. The formation flew at wavetop height across the English Channel, navigating by dead reckoning in weather that made visual navigation nearly impossible. As they approached the French coast near Toqueville, conditions began to clear. The mosquitoes climbed to,500 ft and accelerated.

They flew north of Amu, then turned east, following the Albert to Amu road directly toward the target. At 12:01 p.m., the first wave of six mosquitoes led by Wing Commander Smith approached the prison. The building sat alongside a straight road surrounded by high walls, perfect for a low-level precision attack.

Smith’s aircraft went in first, bombs away at 50 ft. The delayed fuses gave the aircraft time to clear before detonation. The 500lb bombs struck the outer wall with perfect accuracy. Massive explosions breached the wall in two places. The second and third aircraft of the first wave struck the north wall. More breaches opened. The fourth, fifth, and sixth aircraft struck different sections, ensuring multiple escape routes.

The timing was perfect. The bombing was textbook. And then wing commander Audale led the second wave in to strike the prison buildings. His target was the guard’s barracks and the main administrative building. Six more mosquitoes dove toward the prison. More bombs, more explosions. The guard’s quarters were destroyed.

Part of the main building collapsed. Inside the prison, the explosions had blown open cell doors. Walls had collapsed. Debris blocked corridors. But the breaches in the outer walls were clear. Prisoners began running. Group Captain Picard, flying at the rear of the formation, circled at 500 ft to assess the damage. Through the smoke and dust, he could see prisoners escaping through the breached walls.

The mission had succeeded. He signaled the reserve wave to return home. The third wave wasn’t needed. Then he turned for home himself. As Pickards mosquito headed west, a Fauler Wolf 190 from Yagashvada 26 appeared from the clouds. The German pilot on a training flight from the nearby Gizzy Aerad Drrome had been vetoed toward the commotion at Amu.

He spotted Pickicketard’s mosquito. At low altitude, flying slowly, the mosquito was vulnerable. The 190 attacked. A burst of cannon fire severed the mosquito’s tail. The aircraft crashed near the village of Sangrassang. Pickard and his navigator, flight left tenant Alan Broadley, were killed instantly.

French villagers rushed to the crash site and pulled the bodies from the burning wreckage before German troops arrived. They buried Picard and Broadley in the local cemetery with full honors. One mosquito had been lost attacking the target. Squadron leader Mcichie’s aircraft was hit by flack near Albert. He crash landed.

His navigator was killed. Mcichie was captured. Of the escorting Hawker Typhoon fighters, one was shot down and the pilot captured. Another disappeared over the English Channel and was never found. But the mission succeeded. Of 832 prisoners in Amian’s prison on February 18th, 258 escaped. Among them were 79 resistance fighters and political prisoners.

12 who were scheduled for execution got away. The most important escape was Raymond Vivant, a key resistance leader. Twothirds of the escapees were eventually recaptured, but the mission bought time for the most important prisoners. It disrupted German counterintelligence operations and it demonstrated that the allies could strike with precision at targets deep inside occupied Europe.

The cost was high. Picard, one of the RAF’s most famous pilots, was dead. Three other air crew were killed. Three were captured. 102 prisoners died in the bombing. Killed either by the bombs or by guards during the chaos. The controversy over whether Operation Jericho was necessary would continue for decades. Some historians questioned whether mass executions were actually planned.

Others suggested the mission served intelligence purposes that had nothing to do with rescuing prisoners. But for the crews who flew that day, the mission exemplified what the mosquito made possible. Precision attacks on targets that would have required squadrons of heavy bombers and hundreds of crew members could be executed by a handful of aircraft flown by elite crews.

The accuracy was extraordinary. The breaches in the walls were exactly where they needed to be. The damage to the prison buildings was severe, but not total. If the same mission had been flown by B7s or Lancasters, the entire prison would have been obliterated along with everyone inside. Only the Mosquito speed, precision, and the skill of its crews made Operation Jericho possible.

Throughout 1944, as the Allies prepared for and then launched the invasion of Normandy, mosquitoes were everywhere. They photographed the French coast, documenting German defenses. They bombed radar stations and communication centers. They marked targets for heavy bomber raids. They flew intruder missions, hunting German night fighters at their own airfields.

They attacked German headquarters buildings with pinpoint accuracy. On D-Day, June 6th, 1944, mosquitoes flew cover over the invasion beaches. They marked targets for naval gunfire. They attacked German reinforcements moving toward the coast. And throughout the battle of Normandy, they provided close air support, hitting German armor, artillery, and troop concentrations with bombs and rockets.

The fighter bomber variants, armed with eight rocket projectiles and their nose-mounted cannon, were particularly effective against German armor. The salvo of rockets could disable a tank. The cannon could shred soft vehicles, and the mosquito speed allowed it to attack and escape before German anti-aircraft guns could respond effectively.

German troops in Normandy learned to fear the sound of Merlin engines. That distinctive throaty roar meant death from above. The mosquito could appear without warning, strike with devastating accuracy, and disappear before anyone could react. Vermacked commanders reported that daylight movement became nearly impossible in areas where mosquitoes operated.

Convoys had to move at night, troops had to remain undercover, supply columns were decimated. But the mosquito’s greatest contribution to the Allied victory might have been its role in the strategic bombing campaign against Germany. While not capable of carrying the massive bomb loads of Lancasters or B7s, the mosquito could strike targets that heavy bombers couldn’t reach effectively.

High value targets in heavily defended areas, precision strikes on specific buildings, nuisance raids designed to disrupt German industry and force the population into air raid shelters repeatedly. Starting in 1943, mosquito bomber squadrons began conducting regular raids on Berlin. They would fly individually or in small groups, arriving at different times throughout the night.

Each aircraft carried a 4,000 bomb, a blockbuster that could destroy an entire city block. The raids weren’t designed to level Berlin. They were designed to make life in Berlin unbearable. Air raid sirens would sound. The population would rush to shelters. Bombs would fall. The allclear would sound.

People would emerge. An hour later, more mosquitoes would arrive, more sirens, more shelters, more bombs. This continued night after night, week after week, month after month. The psychological effect was devastating. Berliners spent more time in air raid shelters than in their beds. Factory workers were exhausted from interrupted sleep.

The Nazi leadership, which had relocated many government functions to Berlin, found themselves constantly disrupted. And there was nothing the Luftwaffer could do. Night fighters tried desperately to intercept the mosquito raiders. Special units were formed specifically to hunt mosquitoes. The E2 Stanis, a fast twin engine night fighter, was developed partly in response to the mosquito threat.

Later in the war, ME262 jets were assigned to mosquito interception, but the success rate remained painfully low. A mosquito flying at 30,000 ft at 380 mph at night was nearly impossible to intercept. Even when night fighters made contact, the mosquito could often evade. Its maneuverability was excellent for a twin engine aircraft.

Its acceleration was superb, and its pilots, among the most experienced in the RAF, knew every trick in the book. Kurt Welter, a German night fighter race ace, claimed 25 mosquitoes shot down at night and two more by day while flying the ME262. But even he, one of the Luftwaffer’s most successful pilots, flying the most advanced interceptor in the world, found mosquito hunting frustrating and dangerous.

The wooden aircraft was difficult to track on radar. It could outrun his jet if he didn’t position perfectly for the attack, and mosquito crews didn’t die easily. They fought back with skill and determination. By late 1944, the Luftvafer had effectively given up on stopping mosquito raids over Germany.

The resources required to mount effective defenses exceeded the available capability. The fighters that might have hunted mosquitoes were needed to defend against American daylight bomber raids. The radar systems that might have tracked mosquitoes were being destroyed faster than they could be replaced. The fuel that might have powered more interception attempts was running out.

The mosquito owned the night skies over Germany. The statistics of mosquito operations in Europe were staggering. By war’s end, mosquito bombers had flown over 28,000 sorties and dropped 26 and 167 tons of bombs. Mosquito fighter and fighter bomber variants had destroyed 600 German aircraft in aerial combat. They had shot down over 600 V1 flying bombs over England.

They had destroyed thousands of vehicles, locomotives, and railway cars in ground attack operations. And they had done all of this with a loss rate far lower than any other bomber type. The Mosquito’s wooden construction played a significant role in its survivability. Cannon shells that would have torn apart a metal aircraft often passed through wooden structure without exploding.

The wood absorbed battle damage in ways that metal couldn’t. Bullets that struck spars or ribs would lodge in the wood rather than ricocheting around the interior. Even when severely damaged, mosquitoes often made it home. There are accounts of mosquitoes landing with dozens of holes in the wings and fuselage with engines barely running with control surfaces shot away.

The wooden structure held together through damage that would have disintegrated metal aircraft. The production numbers tell another story about why the mosquito was so effective. De Havland and its subcontractors built 7,81 mosquitoes during the war. Production was distributed across multiple facilities.

The main De Havland factory at Hatfield built the majority, but furniture factories throughout England built major components. The wooden construction allowed for distributed production that was less vulnerable to bombing than centralized metal aircraft factories. Standard Motor Company built Mosquitoes. Persal aircraft built them. De Havland Canada built them in Toronto.

De Havland Australia built them. The design was simple enough that non-aircraft companies could produce components to exacting standards. The construction technique essentially highgrade woodworking utilized skills that were widely available. By 1944, Britain was producing mosquitoes faster than Germany could produce fighters to oppose them.

And each mosquito required fewer man-hour to build than a Lancaster Halifax or B7. The efficiency was remarkable, but numbers and statistics don’t fully capture what the mosquito represented to German pilots. The aircraft became a symbol of Allied technological superiority and industrial might. When Guring said the mosquito made him green with envy, he wasn’t just talking about the aircraft’s performance.

He was acknowledging that Britain, despite being bombed, despite being blockaded, despite fighting for its survival, could design and mass-produce an aircraft that Germany couldn’t match. German engineers tried. The fuckwolf tar 150th nicknamed the mosquito by Germans was a direct attempt to copy the concept. Wooden construction twin Merlin engines license built by Dameler Benz high-speed bomber design.

It failed. Production problems with the wooden construction plagued the program. The glue used in assembly deteriorated. Wings separated from fuselages. Aircraft crashed during testing. Only a handful were ever built and they were never used operationally. The HE219 fighter, while effective when it worked, was produced in tiny numbers.

Fewer than 300 were built during the entire war. It could sometimes catch mosquitoes at night, but there were never enough of them to matter. The Mi262 jet was fast enough to intercept mosquitoes, but it came too late and in too few numbers. By the time MI262s were operational in significant numbers, Germany was collapsing. Fuel was scarce.

Pilots were inexperienced. Airfields were being overrun. The jets that might have challenged mosquito supremacy were too little, too late. In the final months of the war, mosquitoes roamed over Germany almost at will. They bombed in daylight. They bombed at night. They photographed targets for bomb damage assessment.

They attacked trains, trucks, and anything that moved. German anti-aircraft gunners fired at them. German fighters tried to intercept them and mosquitoes kept flying, kept bombing, kept coming back. After the war, German pilots and commanders were interviewed extensively about Allied aircraft. When asked about the most difficult aircraft to counter, many mentioned the Mosquito.

General Feld Marshall Hehard Milch, state secretary of the Reich Aviation Ministry, said after the war that the Mosquito was the most versatile aircraft produced by any nation during the war. He acknowledged that Germany had no equivalent and could not have produced one even if they had copied the design exactly.

German test pilots who flew captured mosquitoes after the war were affusive in their praise. The handling was delightful. The performance was outstanding. The visibility was excellent. The construction, while unconventional, was of the highest quality. One German pilot said flying a mosquito was like driving a sports car after years of driving trucks.

But perhaps the most telling assessment came from Adolf Galland, the general of the fighter arm of the Luftwaffer. In his postwar memoir, The First and the Last, Gallon devoted significant attention to the Mosquito. He wrote that the Mosquito was the aircraft he most feared encountering during the war. Not because it was heavily armed, not because it was particularly maneuverable in combat, but because it was impossible to stop.

You could not catch it. You could not shoot it down reliably. You could not prevent it from completing its mission. The speed, the altitude, the construction, the versatility. It was the perfect aircraft for the strategic bombing campaign. He admitted that German fighters could occasionally shoot down mosquitoes, a lucky hit, a mechanical failure, a navigational error that brought the aircraft within range.

But systematic defense against mosquito operations was impossible with the resources available to the Luftvafer. The mathematics didn’t work. The performance gap was too large. The operational tempo was too high. For every mosquito shot down, 10 more completed their missions. For every raid that was intercepted successfully, 20 went unchallenged.

The Mosquito proved that Jeffrey De Havlin’s radical idea was correct. A fast unarmed bomber could survive by speed alone. The Air Ministry experts who rejected the concept were wrong. The conventional wisdom about defensive armorament was outdated. In 1939, most experts believed bombers needed guns to survive. By 1945, the Mosquito had proven that speed was a better defense than any gun turret.

The lessons learned from the Mosquito influenced postwar aircraft design. The English Electric Camber, Britain’s first jet bomber, was designed as a high-speed bomber with no defensive armament. It would rely on speed and altitude just like the Mosquito. The Camber was so successful that the United States licensed it as the Martin B-57.

The concept of the fast reconnaissance aircraft pioneered by the mosquito led directly to aircraft like the Loheed U2 and SR71. These aircraft took the Mosquito’s philosophy to its logical extreme. Fly so high and so fast that interception is impossible. The Mosquito also demonstrated the value of multi-roll aircraft.

Modern fighter bombers like the F-15E Strike Eagle and F-18 Super Hornet owe a conceptual debt to the Mosquito’s ability to perform multiple missions equally well. The Wooden Wonder proved that one good aircraft design could do the work of three or four specialized designs. But beyond its technical legacy, the Mosquito represented something important about the nature of warfare and innovation.

The aircraft that almost wasn’t built, that was rejected by experts, that violated conventional wisdom, became one of the most successful aircraft of the war. Sometimes innovation requires rejecting accepted wisdom. Sometimes the radical idea is the right idea. Sometimes you have to build the aircraft that everyone says is impossible and prove them wrong through performance.

The Mosquito did that. It flew higher, faster, and farther than anyone thought possible for a wooden aircraft. It survived when everyone said it would be shot down. It succeeded in roles that designers never imagined when they first sketched it on drawing boards in 1939. Today, only a handful of mosquitoes still exist.

Most were scrapped after the war. The wooden construction that made them easy to build meant they were also easy to destroy. Wood rots, glue fails. The aircraft that survived combat often didn’t survive peacetime neglect. But the few that remain preserved in museums and maintained by dedicated enthusiasts still inspire awe.

The clean lines, the twin Merlin, the wooden structure that somehow held together through combat that would have destroyed metal aircraft. At the Royal Air Force Museum in London, a mosquito sits in the Battle of Britain Hall. Thousands of visitors see it every year. Most don’t know the full story. They don’t know about the experts who said it would never work.

They don’t know about the German pilots who couldn’t catch it. They don’t know about the missions over Berlin, the precision raids, the desperate attempts to intercept it. They see a beautiful aircraft with wooden wings and wonder how something so fragile looking could have been so effective. But to those who flew it, those who maintained it, and those who tried desperately to shoot it down, the mosquito was anything but fragile.

It was a weapon that changed aerial warfare, a machine that proved speed and altitude could defeat firepower and armor. An aircraft that made the head of the Luftwaffer green with envy. On September 20th, 1941, Squadron leader Rert Clark flew the first operational mosquito mission over France. Three German fighters tried to intercept him.

He simply flew away from them. That pattern would repeat thousands of times over the next four years. German fighters would scramble. They would climb desperately toward the contact. They would watch the mosquito pull away effortlessly, and they would return to base, frustrated, angry, and envious of the machine they could not catch.

The mosquito was built from wood, powered by engines designed before the war, and armed with weapons that were considered inadequate by some experts. Yet, it became the aircraft that the Luftwaffer feared most because it represented a truth that no amount of tactical brilliance could overcome. In modern warfare, the side that can strike with impunity wins.

The side that can reach any target at any time without being stopped controls the battle space. The Mosquito gave the allies that capability. And once the Luftwaffer realized they couldn’t catch it, couldn’t stop it, couldn’t counter it effectively, the psychological victory was as important as any tactical success.

The day the Luftwaffer met the mosquito was the day they realized the war was lost. They just didn’t know it

News

Steve Harvey WALKS OFF After Grandmother Reveals What Her Husband Confessed on His Deathbed

Steve Harvey had hosted Family Feud for over 16 years. And throughout that remarkable tenure, he had become known not…

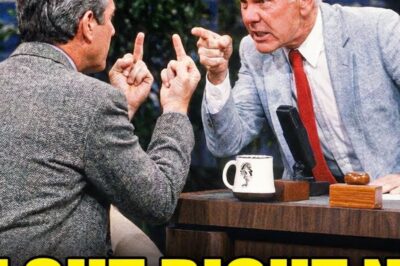

Johnny Carson Reveals 9 “Bastard” Guests He Banned for Life

In Hollywood, there is an unwritten law of survival that every star must engrave in their mind. ] You can…

Steve Harvey KICKED OUT Arrogant Lawyer After He Mocked Single Mom on Stage

Steve Harvey kicked out arrogant lawyer, a story of dignity and respect. Before we begin this powerful story about standing…

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Grandmother’s Answer Made Everyone CRY

Steve Harvey asked a simple family feud question to a 78-year-old grandmother, but her answer was so heartbreaking that it…

Steve Harvey STOPS Family Feud When Contestant Reveals TRAGIC Secret – What Happened Next SHOCKED

Steve Harvey asked a simple family feud question that should have been easy to answer. But when one contestant gave…

Bruce Lee’s unbelievable moment — if it hadn’t been filmed, no one would have believed it

Hong Kong, 1967. In the dimly lit corridors of a film studio. Bruce Lee, perhaps the greatest martial artist in…

End of content

No more pages to load