On October 12th, 1973, a single mistake changed everything for one young man on a Hong Kong film set. His name was Jackie Chan, a 23-year-old American-born Chinese who’d arrived in Hong Kong 6 months earlier with nothing but a backpack and ambition. The film industry was booming. Golden Harvest Studios was churning out martial arts films that would define a generation.

And Bruce Lee, already a legend in Asia on the verge of global superstardom, was at the peak of his powers. Chen needed work. Any work. When the casting call went out for extras on Bruce Lee’s latest production, he didn’t hesitate. 50 Hong Kong dollars for a day’s work. All he had to do was stand in the background, look threatening, and fall down on queue.

It should have been the easiest money he had ever made. The Golden Harvest Lot in Cowoon was a maze of sound stages and temporary structures, a small city within the city. That morning, the air was thick with humidity, the kind that made your shirt stick to your back within minutes of stepping outside. Inside stage 4, where they were shooting the warehouse fight sequence, massive lights pumped even more heat into the already sweltering space.

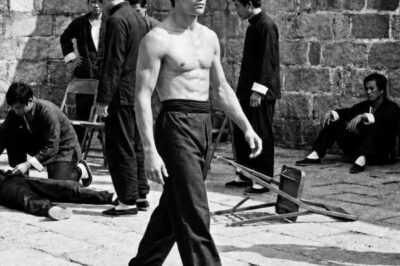

Bruce Lee arrived at 700 a.m. sharp. He was always early, always prepared. The crew knew this about him. Punctuality wasn’t just a preference. It was a philosophy. Time wasted was life wasted, and Bruce Lee didn’t waste life. Chen watched him from across the set as he went through his warm-up routine.

The movements were mesmerizing, fluid, precise, each gesture flowing into the next with no wasted motion. This wasn’t stretching. This was meditation in motion. Several crew members had stopped what they were doing just to watch. “Don’t stare too long,” one of the other extras whispered to Chen in Cantonese. “He doesn’t like being watched during warm-up, makes him self-conscious.

” But Chen couldn’t look away. He’d grown up watching martial arts films, but this was different. This was watching a master craftsman prepare his tools, except the tools were his own body, honed through decades of relentless training. The scene they were shooting was straightforward. Bruce’s character enters a warehouse controlled by a crime syndicate.

Six guards, including Chen and the other extras, attack him one by one. He defeats them all. Of course, the choreography had been worked out in advance. Every punch, every block, every fall had been rehearsed the previous afternoon. Chen’s role was simple. Run at Bruce, throw a right hook. Bruce blocks and counters with a left jab to the ribs. Chen falls left.

They’d practiced it a dozen times. The stunt coordinator had been satisfied. “Perfect,” he’d said. “Just do that when the cameras roll.” At 9:47 a.m., the assistant director called for positions. Chen took his spot near a stack of wooden crates, trying to channel every movie tough guy he’d ever seen. The other extras flanked him, all of them doing the same thing, puffing their chests, narrowing their eyes, trying to look dangerous.

Bruce Lee stood in the center of the set, perfectly still. His eyes were closed. He was breathing slow, deep, rhythmic, centering himself. When he opened his eyes, something had changed. He wasn’t Bruce Lee anymore. He was the character. The transformation was complete. Quiet on set, the first assistant director shouted.

The soundstage fell silent. 70 people holding their breath. Camera rolling action. The first extra attacked. Bruce side stepped, struck. The man fell. Perfect. The second came in from the right. Block counter down. Beautiful. The third, fourth, fifth. All went exactly as choreographed. The movements were so clean, so precise they looked almost bettic. Chen was last.

He took a breath, remembering his cue. Run forward. Throw the punch. Let Bruce block. Fall left. Simple. He ran forward. Later, he would try to remember exactly what went wrong. Did he step too close? Did he throw the punch at the wrong angle? Did he telegraph his movement differently than in rehearsal? The stunt coordinator would review the footage dozens of times, and even he couldn’t pinpoint the exact moment things deviated from the plan.

What everyone agreed on was this. Chen threw his punch and Bruce Lee’s counter came fast. Not stage fighting fast, not choreographed fast, combat fast, real fast, the kind of speed that exists in the space between thought and action. His fist connected with Chen’s jaw with a sound that echoed across the sound stage, a sharp, clean crack that made several crew members wse.

Chen’s world tilted. The lights above became streaks. The floor rushed up to meet him. There was a moment of strange clarity, a split second where he could see everything with perfect detail. The grain of the wooden floor, the dust moes floating in the air. Bruce Lee’s face shifting from focus to horror.

Then everything went white. The set erupted. Crew members rushed forward. Someone shouted for the medic. The director was yelling in Cantonese, asking what happened. The assistant director was already on the phone with the production office, no doubt worried about liability, insurance, lawsuits. But Bruce Lee was already at Chen’s side, kneeling, his face a mask of concern.

When Chen’s eyes fluttered open 10 seconds later, though it felt like hours, Bruce was the first face he saw. Don’t move, Bruce said in English, then repeated it in Cantonese for the medic who was approaching. We need to check for concussion. Chen’s jaw felt loose, disconnected, like it belonged to someone else.

He could taste copper blood, his own. I’m okay, he managed to say, though the words came out slurred. You’re not okay, Bruce said flatly. You just took a full contact hit to the jaw. We’re shutting down for the day. The producer, a heavy set man named Wong, who’d been watching from behind the monitors, started to protest.

We’re already behind schedule. If we lose today, Bruce turned to look at him. It wasn’t an angry look. It was simply a look of complete certainty. We’re done, he said. I’m not shooting another scene until I know he’s all right. Wong deflated immediately. Nobody argued with Bruce Lee when he used that tone. But what happened next was what Chen would remember most clearly, even years later, when the details of the accident itself had faded into impressions and feelings rather than concrete memories.

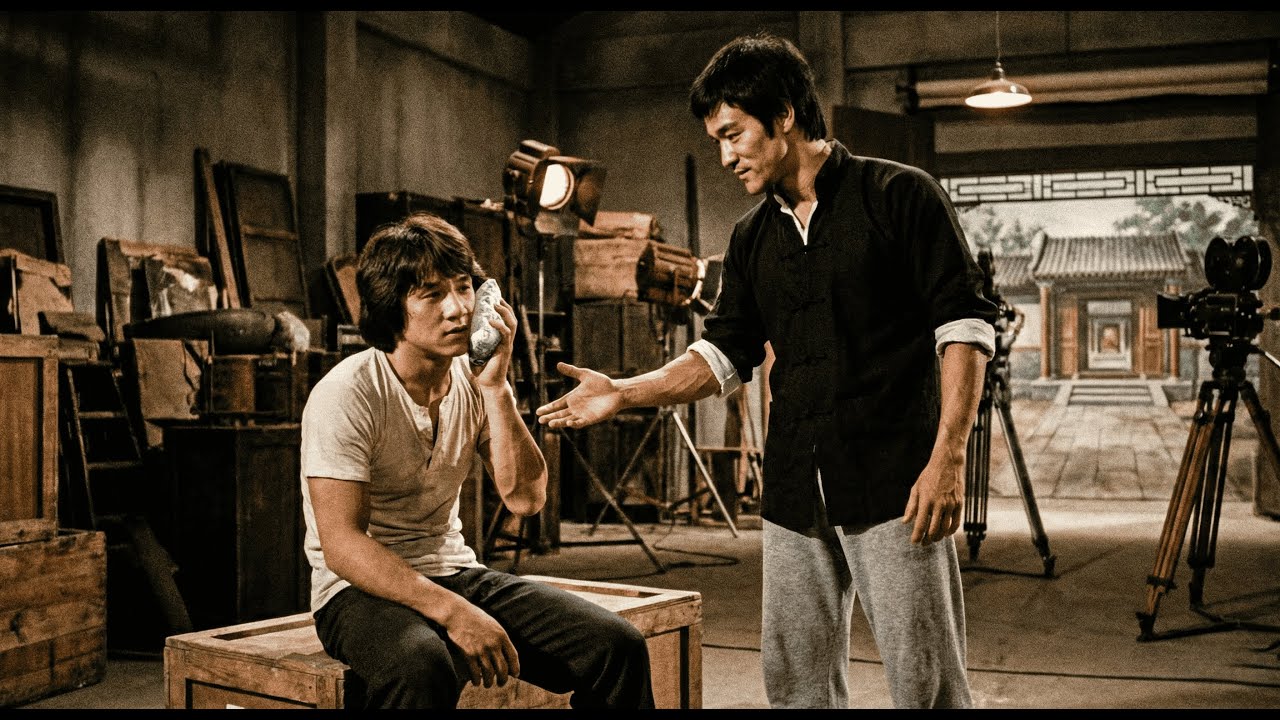

Bruce Lee took personal responsibility. He helped Chen to his feet himself, supporting him when his legs wobbled. He dismissed the medic politely but firmly and instead took Chen to his own trailer. He made tea. He sat with him. He apologized genuinely and repeatedly as if he’d committed some unforgivable sin rather than simply reacted instinctively during a stunt gone wrong.

In real fighting, Bruce explained as they sat in his trailer, the sound of the crew packing up equipment filtering in from outside. Your body reacts before your mind decides. You train for thousands of hours so that the response becomes automatic. But that’s dangerous on a film set because film fighting isn’t real fighting.

The movements are similar, but the intent is completely different. He poured more tea. His movements precise even in this domestic task. I lost awareness for a moment. I was thinking about the shot, about the angle, about whether we were getting the take the director wanted. I wasn’t thinking about you, about your safety. That’s my failure, not yours.

Chen wanted to argue, wanted to say it was his fault for throwing the punch wrong, but his jaw hurt too much to speak for long. The problem with being good at something, Bruce continued, is that it becomes so automatic you stop thinking about it. That’s when accidents happen. That’s when people get hurt.

He looked directly at Chen. I’m sorry. This shouldn’t have happened. They sat in silence for a while. Outside, the last of the crew were leaving, calling goodbyes to each other, making plans for dinner. Inside the trailer, there was just the two of them in the fading light of afternoon coming through the small window.

Bruce Lee was supposed to be intimidating. That’s what everyone said. intense, demanding, perfectionist, and he was all of those things. But sitting in that trailer, drinking tea, Chen saw something else. A man deeply committed to his craft, but also deeply aware of his responsibility to the people around him. You know what my teacher used to tell me? Bruce asked suddenly.

Itman, the Wing Chun master. He used to say that the best fighter is the one who never has to fight. Not because he’s a coward, but because he sees the conflict coming so far in advance that he can step around it. He smiled slightly. I didn’t see this coming. That makes me a poor student even now. By the time Bruce insisted on driving Chen home, and it was an insistence, not an offer.

The sun was setting over Hong Kong, painting the sky in shades of orange and purple. The city was coming alive for the night. Neon signs flickering on, street vendors setting up their stalls, the endless rhythm of Hong Kong life pulsing through the streets. They drove in comfortable silence for most of the journey. Bruce navigated the chaotic traffic with the same precision he brought to everything else.

Smooth, efficient, aware of every vehicle around him. When they pulled up outside Chen’s apartment building in Cowoon, a run-down place with peeling paint and laundry hanging from every balcony, Bruce put the car in park, but didn’t immediately let Chen out. “Take tomorrow off,” he said. “Rest.

If your jaw swells or you have any dizziness, go to a doctor. Tell them to build Golden Harvest directly. I’ll make sure it’s covered. I’ll be fine,” Chen said, though he wasn’t entirely sure. “Probably,” Bruce agreed. “But we don’t take chances with head injuries. Promise me you’ll rest,” Chen promised. “Good,” Bruce paused, his hands still on the steering wheel.

“You know, in all the films I’ve made, all the fights I’ve choreographed, I’ve never seriously hurt anyone. Not once until today.” He looked at Chen. I don’t want that to be my legacy. I don’t want people to remember me as someone who hurt people even accidentally. They won’t. Chen said, “They’ll remember you for everything else.

For changing cinema, for showing the world what martial arts really are.” Bruce smiled slightly. Maybe, but I’ll remember today. I’ll remember that I wasn’t aware enough, wasn’t present enough, and I’ll do better. Chen watched as Bruce’s car disappeared into the Hong Kong night, its tail lights fading into the river of traffic.

He climbed the four flights to his apartment, each step a reminder of what had happened, his jaw throbbing in time with his heartbeat. The accident made the Hong Kong papers the next day. Bruce Lee, injures extra on set, read the headline in the South China Morning Post. The article was brief, factual, noting that filming had been suspended and that the injured party was receiving medical care.

It made it sound more dramatic than it had been. What the papers didn’t report was the 2hour conversation in the trailer. They didn’t mention the tea ceremony, the philosophy, the genuine concern. They didn’t know about the personal apology, the offer to cover medical expenses, the insistence on driving Chen home personally.

The public saw the headline. Chen saw the human being behind it. He returned to the set 3 days later, his jaw still tender but functional. Bruce Lee was the first person to approach him. How are you feeling? Better? Ready to work? Bruce studied him for a moment as if assessing whether he was telling the truth. Then he nodded.

Good. But we’re changing the choreography for your scene. Something simpler, safer. You don’t have to. I know I don’t have to. I want to. Bruce’s tone left no room for argument. Besides, I’ve been thinking about that sequence. It was too complicated anyway. Sometimes the simplest movements are the most effective.

They reshot Chen’s scene that afternoon. The new choreography was indeed simpler, a push rather than a punch, a stumble rather than a dramatic fall. It took one take. Bruce was satisfied. The director was satisfied. And Chen walked away without a single bruise. The film was released 6 months later to massive success.

Chen’s moment on screen lasted 3 seconds. If you blinked, you missed him entirely. But he went to the premiere anyway, sat in the back of the theater, and watched as the audience cheered for every fight scene. When his moment came, the brief shot of him stumbling backward after Bruce’s push, he smiled.

Nobody in the audience knew the story behind that simple movement. Nobody knew about the accident, the apology, the tea, the conversation about awareness and presence. But Chen knew. And somehow that was enough. Bruce Lee died less than a year later. July 20th, 1973. A cerebral edema. He was 32 years old. The news hit Chen like a physical blow.

almost as hard as the punch itself had been. In the decades that followed, as Bruce Lee’s legend grew to mythic proportions, Chen would occasionally be asked about his brief time working with him. What was he really like? People wanted to know. Was he as intense as they say, as demanding, as perfect? And Chen would tell them, “Yes, Bruce was all of those things.

But he was also humble enough to apologize when he made mistakes. Caring enough to check on an injured extra. Human enough to sit and drink tea and talk about philosophy with a nobody who’ just messed up a stunt. The punch hurt, Chen would say. But the apology changed my life. He never worked in films again.

The industry wasn’t for him. Too chaotic, too unpredictable. But the lesson from that day stayed with him through everything that came after. the importance of being present, of taking responsibility, of understanding that skill without awareness is dangerous, and that the greatest mastery comes not from never making mistakes, but from how you handle them when you do.

Years later, Chen would have a son. When the boy was old enough, Chen took him to watch Enter the Dragon, Bruce Lee’s masterpiece, the film that introduced him to Western audiences and cemented his status as a global icon. As they sat in the dark theater watching Bruce move across the screen with that impossible grace, the boy turned to his father and whispered, “Did you really meet him? Did he really hit you?” Chen touched his jaw instinctively, even though the pain had long since faded.

Yes, he hit me and then he made me tea and drove me home. The boy’s eyes widened. Really? Really? On screen, Bruce Lee fought and won as he always did, but Chen wasn’t watching the fight. He was remembering the moment after in a modest trailer, drinking jasmine tea with a legend who was humble enough to apologize for being human.

That was the Bruce Lee nobody saw on screen. That was the man behind the legend. And that, Chen thought as the credits rolled, was the story worth telling.

News

Steve Harvey WALKS OFF After Grandmother Reveals What Her Husband Confessed on His Deathbed

Steve Harvey had hosted Family Feud for over 16 years. And throughout that remarkable tenure, he had become known not…

Johnny Carson Reveals 9 “Bastard” Guests He Banned for Life

In Hollywood, there is an unwritten law of survival that every star must engrave in their mind. ] You can…

Steve Harvey KICKED OUT Arrogant Lawyer After He Mocked Single Mom on Stage

Steve Harvey kicked out arrogant lawyer, a story of dignity and respect. Before we begin this powerful story about standing…

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Grandmother’s Answer Made Everyone CRY

Steve Harvey asked a simple family feud question to a 78-year-old grandmother, but her answer was so heartbreaking that it…

Steve Harvey STOPS Family Feud When Contestant Reveals TRAGIC Secret – What Happened Next SHOCKED

Steve Harvey asked a simple family feud question that should have been easy to answer. But when one contestant gave…

Bruce Lee’s unbelievable moment — if it hadn’t been filmed, no one would have believed it

Hong Kong, 1967. In the dimly lit corridors of a film studio. Bruce Lee, perhaps the greatest martial artist in…

End of content

No more pages to load