October 1980, Chicago. The set of The Big Brawl buzzed with controlled chaos as cameras, crew members, and martial arts choreographers moved through their routines. But on this particular afternoon, something unprecedented was about to happen. Something that would become one of Hollywood’s most whispered moments.

Jackie Chan stood near the craft services table, his body language betraying his frustration. At 26 years old, he was already a superstar in Hong Kong. Films like Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow and Drunken Master had made him a household name across Asia. Producers fought over him. Directors trusted him with million-doll budgets.

Audiences packed theaters just to see his name on a poster. But here in America, he was nobody. just another Asian actor being marketed as the new Bruce Lee, a replacement, a copy. The thought burned in his chest every single day. Bruce Lee had died 7 years earlier, and Hollywood still couldn’t move past him. Every Asian martial artist who stepped onto American soil was immediately measured against a ghost.

And Jackie Chan, comedic, acrobatic, innovative Jackie Chan, didn’t fit the mold. His English was terrible. Conversations with the director required translators, which made him feel like a child. His agent kept telling him to smile more, to be more American, whatever that meant. The director of the big brawl kept comparing his moves to Bruce Lee’s, asking him to punch more like that, to scowl more like that, to be more serious, more intense, more not Jackie.

The film itself was a mess. Robert Clus, who had directed Enter the Dragon with Bruce Lee, was at the helm. But Claus didn’t understand Jackie’s style. He didn’t understand that Jackie’s genius wasn’t in being fierce. It was in being clever, in using props, environments, and his own body in ways that made audiences laugh and gasp at the same time.

But Hollywood didn’t want clever. Hollywood wanted another Bruce Lee. Jackie had broken bones for this film. He’d done stunts that terrified American stunt coordinators. He’d thrown himself downstairs, crashed through furniture, taken hits that would hospitalize most actors. And for what? Test screenings were lukewarm. Studio executives were non-committal.

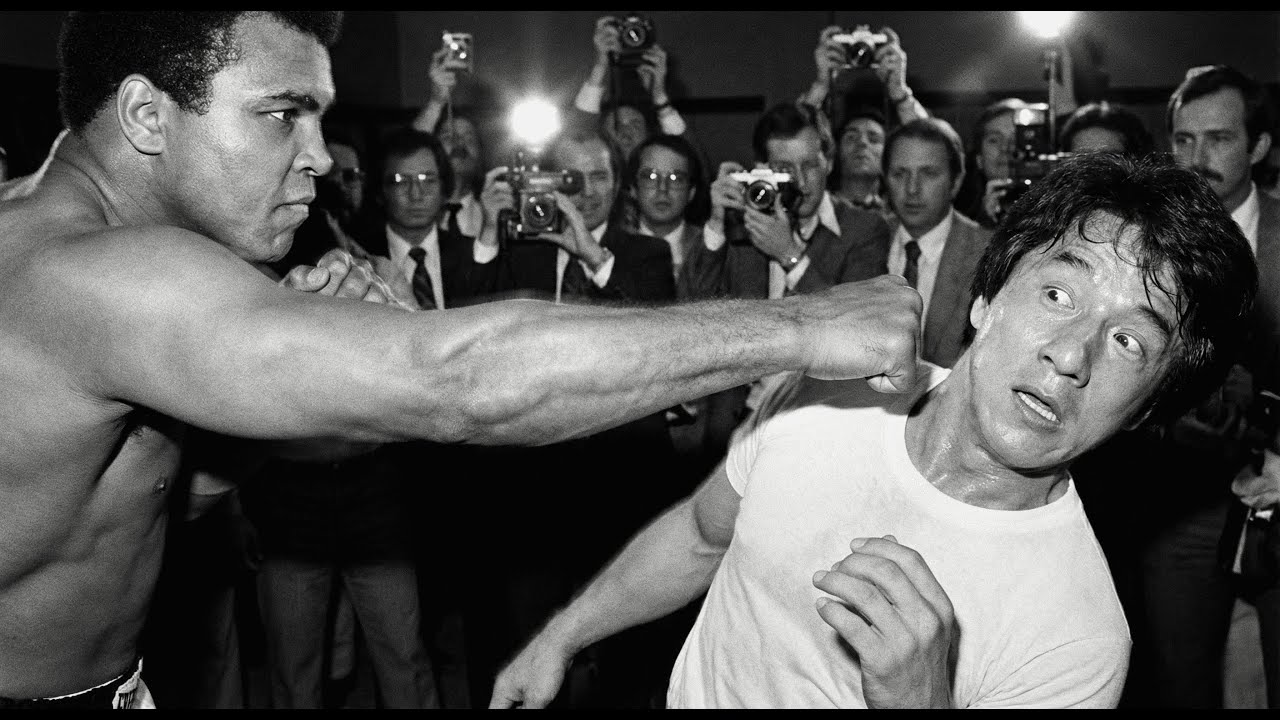

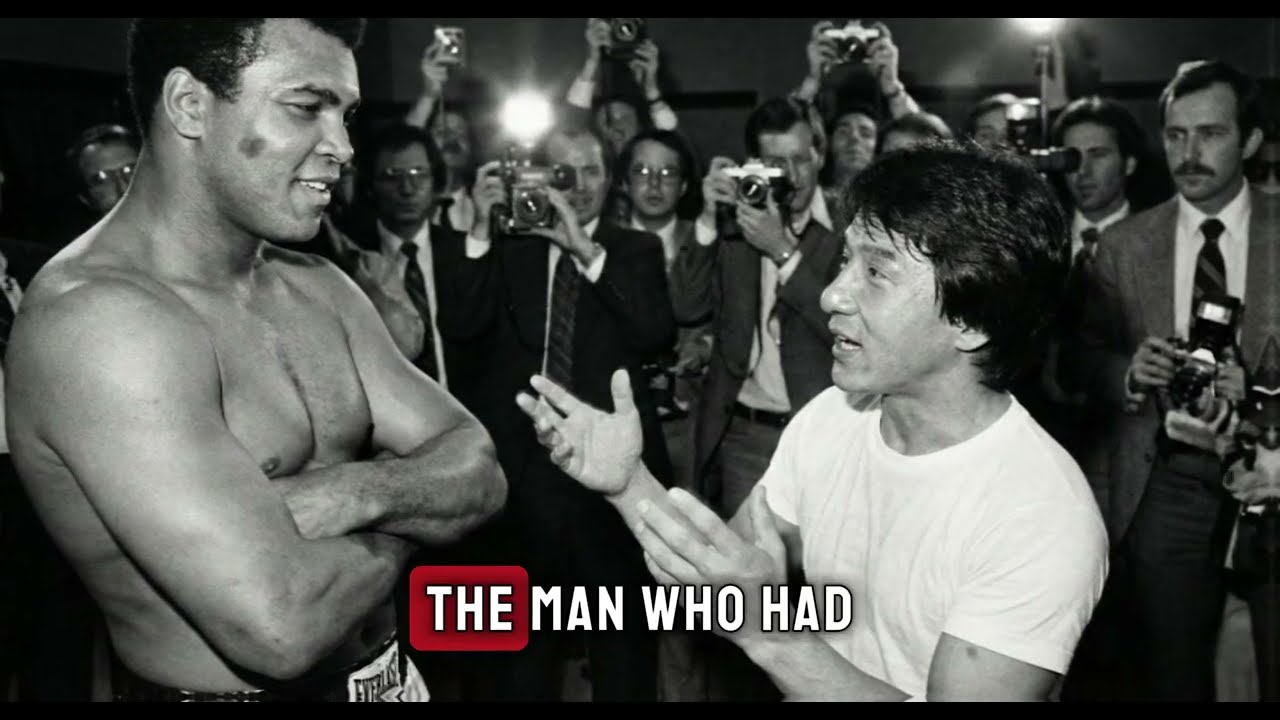

The whispers were already starting. Maybe the Asian market doesn’t translate. Maybe we made a mistake. The weight of potential failure pressed down on Jackie’s shoulders every morning when he arrived on set. Then Muhammad Ali walked through the door. The greatest, the Louisville lip, the man who had floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee.

The man who had refused to go to Vietnam and lost everything only to win it all back. The man who had beaten Sunny Lon, George Foreman, and Joe Frasier. The man who had transcended sports and become something else entirely. a cultural icon, a poet, a prophet. At 38, Ally had just lost to Larry Holmes two weeks earlier in a brutal one-sided fight that many said should never have happened.

His hands trembled slightly, early signs of the Parkinson syndrome that would later define his final decades. His speech was a fraction slower than it had been in his prime. His body, once a perfect instrument of violence and grace, was beginning to betray him. But when Muhammad Ali entered a room, he still owned it.

His presence was gravitational. Someone from the production team had invited Alli to visit the set. A publicity stunt, most likely get photos of the boxing legend with the Kung Fu Kid. Good press for a movie that desperately needed it. The big brawl was Jackie’s shot at American stardom. But early test screenings weren’t promising.

The film felt confused, caught between Jackie’s acrobatic comedy style and Hollywood’s expectations of what a kung fu movie should be. Ali moved through the set like he was floating. People parted naturally, unconsciously. Crew members whispered, cameras flashed. A production assistant scrambled to find the director.

And Jackie Chan watched from the periphery, his arms crossed, his jaw tight. Here was another legend, another icon, another person who would probably look at Jackie and see only Bruce Lee’s shadow. But then Alli’s eyes found Jackie’s. Something passed between them in that first moment. Recognition perhaps, not of faces, but of something deeper.

Two men who had spent their entire lives being told they couldn’t do something and then doing it anyway. two men who had changed their respective arts through sheer force of will and impossible talent. “Hey, you’re the kung fu cat they’ve been telling me about,” Ally said, his voice carrying that familiar playful rhythm.

He approached Jackie with an extended hand, his smile wide and genuine. “You supposed to be fast, right?” “That’s what they tell me. Fast like lightning.” Jackie shook his hand, nodding. His English failed him in the moment, but he managed. Yes, very fast. Allie’s eyes sparkled with mischief.

That dangerous, playful look that had preceded a thousand verbal knockouts. Fast like me. The crew had started gathering now. Sensing something, a moment. Ally was known for these impromptu performances, verbal jousting matches, spontaneous demonstrations of his genius. He’d done it with reporters, with other fighters, with presidents and poets and everyone in between.

And now, apparently with a frustrated Hong Kong stunt man trying to make it in America. Maybe, Jackie said carefully. His English was broken, but his competitive spirit was fluent in every language. Maybe faster, Ally laughed. That booming, infectious laugh that had charmed the world. Oh, you got jokes. I like this kid already. He turned to the crowd forming around them.

This little man here think he faster than Muhammad Ali. The crew laughed, but it was warm, encouraging. They wanted to see where this was going. Because when Muhammad Ali started playing, magic usually followed. Jackie felt something shift in his chest. Not anger, not embarrassment, recognition. Ali wasn’t mocking him.

He was inviting him into something, a dance, a game, the kind of playful challenge that separates legends from everyone else. The kind of moment that defines careers, and Jackie Chan had never backed down from a challenge in his life. What happened next would depend on who you asked. Some crew members would later say Jackie initiated it. Others swore it was Ally.

But the consensus was clear. Someone issued a challenge, and someone accepted. Robert Claus, the director, had arrived by then. He saw what was happening and had the good sense to stay quiet and keep rolling. Whatever was about to occur, it was better than anything in the script. “You know what?” Ally said, taking a step back and raising his hands in a loose boxing stance.

His movements were slower than they’d been in his prime, but the muscle memory was still there. The stance was perfect. Show me what you got. Show me that Hong Kong speed. Jackie’s eyes narrowed. This was it, his moment. Not to prove he was the next Bruce Lee. Not to satisfy some Hollywood executives checklist, but to show Muhammad Ali, the man who’d beaten Sunny Liston, George Foreman, and Joe Frasier, what Jackie Chan could do.

He dropped into his stance, low, balanced, his feet positioned in the classical southern Chinese martial arts style he’d learned at the Piking Opera School. His hands moved in small circles, the way his opera school teachers had drilled into him for years. The Peeking Opera School didn’t just teach you to fight. It taught you to move like water, to make your body an instrument of impossible precision.

The set had gone completely quiet. Even the ambient noise of Chicago traffic outside seemed to fade. Cameras were still rolling. Someone had the presence of mind to keep filming. This wasn’t in the script, but it was better than anything in the script. “Come on, kid,” Ally said, his voice dropping to that dangerous whisper he used before fights.

That tone that had preceded the destruction of so many opponents. “Try to hit me. Try to hit me.” Three words that would echo in Jackie’s memory for the rest of his life. Jackie moved. His first strike came fast. A straight punch aimed at Alli’s solar plexus, pulled enough not to injure, but thrown with real intent.

Allie’s torso shifted two inches to the left. The punch cut through empty air where his body had been a fraction of a second before. Jackie followed immediately with a back fist, a classic follow-up. Ally leaned back, his head moving just enough. The backfist whispered past his chin. Another miss. Jackie had trained since he was six years old, 7 hours a day, every day for years.

Acrobatics, martial arts, acting, singing. The peaking opera school had beaten perfection into him through repetition and pain. He’d done thousands of takes, perfected impossible stunts, broken nearly every bone in his body, and bled for his craft. His hands were weapons. His body was a machine built for precision.

But Muhammad Ali had fought in the ring against the most dangerous men on the planet. And right now, Alli was reading Jackie like a children’s book. Jackie threw a low kick, a faint designed to draw Alli’s attention downward. Ally didn’t bite. His eyes never left Jackie’s centerline. Reading the telegraphs in his shoulders and hips, Jackie spun, launching a hook punch that should have connected with Alli’s jaw. Should have.

But Ally pulled his head back with that supernatural timing that had frustrated fighters for two decades. His famous rope a dope defense wasn’t just about leaning on the ropes. It was about knowing exactly where a punch would be and making sure his face wasn’t there. Three strikes, three misses. Jackie reset, breathing harder now. Not from exertion.

His conditioning was legendary, but from the concentration required. The crew was dead silent. Even the cameras felt like they were holding their breath. “That’s real nice,” Ally said, not even winded. “Real pretty. You move like water, kid, but you ain’t touched me yet. Jackie’s pride flared.

He’d been holding back, trying to be respectful, trying not to embarrass the aging legend. But Ally was challenging him. Really challenging him. The competitive fire that had driven Jackie to jump off buildings and crash through glass was suddenly roaring. So Jackie did what he did best. He attacked for real.

The next combination came in a blur. punch, elbow, knee, spinning back fist. A sequence that would have hospitalized most people. Jackie’s speed was legitimate. His technique was flawless. These weren’t movie punches designed to look good on camera. These were real strikes pulled just enough to avoid actual contact, but thrown with genuine intent and full speed.

And Ally dodged them all. Not by much, inches, centimeters. His head bobbed, weaved, slipped. His feet didn’t even move that much. He was doing it all with upper body movement. That legendary defensive genius that made him one of the greatest boxers ever to live. The same defense that had frustrated George Foreman and Zire.

The same slips that had made Joe Frasier miss. The same head movement that had defined an era. Jackie threw eight strikes in 3 seconds. Eight perfect strikes. Ally avoided all of them. But then Ally did something Jackie wasn’t expecting. He hit back. Not hard, not even close to hard, but Alli’s jab, that legendary left hand that had set up a thousand combinations that had knocked out Cleveland Williams that had blinded Henry Cooper, flicked out like a snake’s tongue and tapped Jackie on the forehead.

Barely a touch, a love tap, but undeniable contact. Jackie froze. Ally grinned, his hands already dropping, his posture relaxing. Gotcha. The set exploded. Crew members erupted in laughter, applause, shouts of amazement, not mocking laughter. Delighted laughter, the kind of joy that comes from watching two masters of their crafts play together at the highest level.

Cameras had caught it all. Ali was laughing too, his arms raised in victory like he’d just won another title, playing to the crowd like he always did. And Jackie Chan, proud, frustrated, desperate to prove himself, Jackie Chan, felt his face burn red. For exactly 3 seconds, he regretted every decision that had led to this moment.

Regretted opening his mouth, regretted accepting the challenge. regretted thinking even for a moment that he could touch Muhammad Ali. The embarrassment was total and complete. But then Alli’s hand landed on his shoulder. “Kid,” Alli said, his voice lower now meant just for Jackie. The crowd noise faded to background. “You got something special.

I ain’t just saying that. You got speed, you got skills, you got heart. I seen it.” He squeezed Jackie’s shoulder, his grip still strong despite the tremor. “But you know what you really got?” Jackie looked up at him, his English failing him again, but his eyes asking the question, “You got style,” Ally continued.

“Your own style, not that other cat’s style. Yours, and that’s worth more than being fast. That’s worth more than being strong. That’s worth more than anything.” Something cracked open in Jackie’s chest. Not humiliation, understanding. Ally wasn’t just playing with him. He was teaching him. The same way Ally had taught the world about more than boxing, about standing up for your beliefs, about being yourself in a world that wanted you to be someone else, about transcending the limitations others put on you.

Don’t let them make you into somebody else. Ali said. And now his voice carried weight. Wisdom. The kind of truth that only comes from living through hell and coming out the other side. You be Jackie Chan. That’s enough. That’s more than enough. You hear me? Jackie nodded. He heard these people. Alli gestured at the set at Hollywood at America.

They don’t know what they got yet, but they will. You just keep being you. Do your thing your way, not their way. Robert Clus was watching from behind the camera, his expression unreadable. Years later, he would claim he knew in that moment that he’d been directing Jackie Chan wrong, that he’d been trying to fit a square peg into a round hole.

But the film was too far along to change course. The cameras had caught all of it. the challenge, the misses, the tap, the lesson. None of it would make it into the big brawl. The footage would be filed away, shown to crew members at rap parties, whispered about in industry circles, but it wouldn’t be released publicly. Not for years.

Because what happened on that set wasn’t about publicity. It wasn’t about marketing or box office or any of the things Hollywood cared about. It was about two fighters, one at the end of his legendary career, one struggling to start his recognizing something in each other that the world hadn’t seen yet. The Big Brawl would flop when it was released in 1980.

Critics would savage it. Roger Eert would call it a disappointment. Audiences would ignore it. Jackie would feel that failure like a physical wound. He’d returned to Hong Kong, convinced his American dream was dead, convinced that Hollywood would never understand him. He’d spend the next decade perfecting his craft, creating films that blended comedy, action, and heart in ways Hollywood had never seen.

Movies like Police Story, Project A, Armor of God, and Dragons Forever. Films that were undeniably, unmistakably Jackie Chan. Films where he could be funny and vulnerable and human while doing stunts that defied physics. No more comparisons to Bruce Lee. No more trying to fit into someone else’s shadow. Just Jackie being Jackie. It would take Hollywood 15 years to catch up.

When Rumble in the Bronx broke through in 1995 when Rush Hour became a massive hit in 1998, American audiences would finally understand what the rest of the world had known for decades. Jackie Chan wasn’t the next anyone. He was the first Jackie Chan. Years later in interviews, Jackie would sometimes reference that day.

He’d smile, shake his head, and say something about learning respect from the greatest boxer who ever lived. He’d never go into details, never explain exactly what Ally said or did. Some moments are too personal, too formative to share with the world. But people who were there remembered. They remembered a 26-year-old kung fu fighter.

frustrated and lost, trying to prove himself to a country that didn’t want him. They remembered Muhammad Ali, two weeks removed from the most punishing loss of his career, still sharp enough to teach a lesson without throwing a real punch. They remembered the sound of Ali’s hand tapping Jackie’s forehead. Gotcha. 3 seconds of regret, followed by a lifetime of gratitude.

Because that day, Jackie Chan learned something more valuable than speed, more important than technique, more lasting than any Hollywood contract. He learned to be himself. And Muhammad Ali, the greatest, taught him how. On that Chicago set in October 1980, two legends met. One was ending his journey. One was just beginning, but for a few minutes they stood on common ground, speaking a language that transcended words.

the language of champions.

News

How a Black Female Sniper’s “Silent Shot” Made Germany’s Deadliest Machine Gun Nest Vanish in France

Chicago, winter 1933. The Great Depression had settled over the Southside like a fog that wouldn’t lift. The Carter family…

Polish Chemist Who Poisoned 12,000 Nazis With Soup — And Made Hitler Rewrite German Military Law

The German doctors at Stalag Vic never suspected the mute Polish woman who scrubbed their floors. November 8th, 1944. Hemer,…

This Canadian Fisherman Turned Sniper Killed 547 German Soldiers — And None Ever Saw Him

November 10th, 1918. 3:37 in the morning, a shell crater in Belgium, 40 yards from the German line. Silus Winterhawk…

They Called Him a Coward for Refusing to Fire — Then His ‘Wasted’ 6 Hours Saved 1,200 Lives

At 11:43 a.m. on June 6th, 1944, Private Firstclass Daniel McKenzie lay motionless in the bell tower of St. Mirly’s…

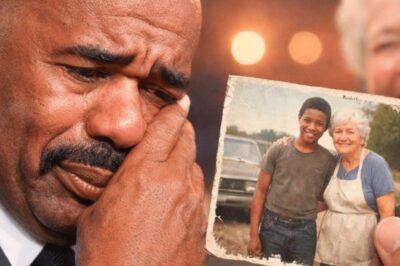

Steve Harvey Stopped Family Feud After Seeing This

The studio lights were blazing. 300 people sat in the audience, their faces bright with anticipation. The Johnson family stood…

He Was a Hungry Teen — Until One Woman Changed His LifeForever

Steve Harvey stands frozen. The Q cards slip from his fingers and scatter across the studio floor. 300 audience members…

End of content

No more pages to load