Fuaktui Province, South Vietnam, March 17th, 1966. The Vietkong sentry never heard them coming. Nuan Vanam had survived 2 years in the jungle, learned to detect American patrols from half a kilometer away by the smell of their cigarettes and bug spray, could identify helicopter types by sound alone in complete darkness.

But the four men who materialized from the triple canopy jungle moved like smoke through water. No radio chatter, no cigarette glow, no obvious trail signs. When Tam turned to wake his comrade at 342 hours, a gloved hand covered his mouth and a blade ended his war in absolute silence. Three other sentries died the same way within 90 seconds.

The VC base camp, 18 fighters, two weapons caches, a communications relay, ceased to exist by 0400. By row 430, the attackers had vanished back into the jungle, leaving only bodies arranged in a specific pattern. A calling card. The Australian SAS had arrived in Vietnam. In Hanoi, intelligence officers would spend the next three years trying to understand how these ghost soldiers operated.

Unlike the Americans with their massive search and destroy operations, artillery barges, and helicopter assaults, these men hunted with surgical precision. No second chances, no survivors to tell tales, just empty camps and a growing legend that would make the Vietkong fear the jungle itself. The Americans would fight the war their way, big, loud, and technological.

The SAS would fight it theirs, silent, patient, and absolutely lethal. When the first Australian and British SAS advisers arrived in Southeast Asia in the early 1960s, American commanders were skeptical. Major General William West Morland reviewing Allied contributions in 1964 noted in a memo, “The British offer expertise in counterinsurgency.

Whether their methods suit our operational tempo remains to be seen. The Americans had firepower, mobility, and modern doctrine. They had M16s, Hueies, artillery support on demand, and B-52s for anything truly serious. What could a small contingent of soldiers from a fading empire possibly teach them? The British and Australian SAS had something else entirely.

12 years of experience defeating communist insurgents in the Malayan emergency. They’d perfected the art of long range jungle patrolling, small unit operations, and hearts and minds counterinsurgency. They’d learned patience in places where patience meant survival. The Americans wanted to find the enemy and destroy him with maximum force, recalled British SAS Major Peter Walsh, who served as an adviser in 1963-64.

We wanted to understand him first, then remove him surgically. Different philosophies entirely. Early joint operations revealed stark contrasts. An Australian SAS squadron could patrol for 2 weeks on what an American infantry platoon consumed in 3 days. They moved through jungle without breaking branches, set ambushes that waited for days, and communicated with hand signals that eliminated radio chatter.

American advisers watching Australian SAS training exercises were impressed, but unconvinced these tactics would scale. The Pentagon’s thinking was rooted in overwhelming force in attrition warfare. Search and destroy operations would find large enemy formations and obliterate them with superior firepower. Body counts would measure progress.

Technology would overcome terrain disadvantages. The SAS approach seemed almost quaint by comparison. four to six-man teams, minimal contact, maximum intelligence gathering, precise targeting of high-v valueue individuals and logistics. It was counterinsurgency as scalpel versus hammer. Vietnamese communist commanders initially dismissed reports of these new operators as exaggerations.

They’d fought the French, survived American bombing, and controlled vast swaths of jungle. A few dozen foreign soldiers in the bush seemed irrelevant compared to divisions of American troops. That perception would change violently. The Australian SAS regiment arrived in Fuaktu province in 1966 as part of the Australian task force commitment to Vietnam.

Unlike their American counterparts, organized into large infantry battalions, the Australians deployed in squadron strength, roughly 110 dorna 120 men who would operate primarily in small patrol units. These weren’t regular soldiers playing at special operations. The SAS regiment drew from Australia’s finest soldiers who’d survived selection courses with 90% failure rates.

Men trained in the same tradition as Britain’s legendary 22 SAS regiment. Many had studied Malayan emergency veterans, learning lessons written in jungle blood over 12 years of counterinsurgency. Their training emphasized what Americans largely ignored. Silent movement, tracking, observation, and patience. and says patrol could lie motionless for 16 hours watching an enemy trail, then execute a perfect ambush in 30 seconds and vanish before reinforcements arrived.

British SAS advisers, though fewer in number, brought even deeper expertise. They trained with Girkas, fought in Borneo, and developed tactics for jungle warfare that contradicted conventional military wisdom. We learn to think like hunters, not soldiers, explained Sergeant John Lofty Large, a British SAS adviser in 1965. Patience wasn’t just virtue, it was survival.

The Americans used helicopters as taxis, flying into landing zones with maximum noise. The SAS used them sparingly, often walking dozens of kilometers to insertion points to avoid alerting the enemy. American patrols might number 30 to 40 men. SAS patrols typically ran four to six men, small enough to hide, large enough to fight briefly if discovered, and trained to break contact rather than stand and fight.

Their weapon preferences revealed philosophical differences. Americans carried M16s with full automatic capability. SAS preferred L1A1 self-loading rifles and suppressed Sterling submachine guns, semi-automatic precision versus spray and prey. Every round counted when resupply required days of walking. The intelligence gathering focus separated them further.

While American units measured success in enemy KIA, SAS patrols prioritized intelligence, photographing documents, tracking movement patterns, identifying supply routes, capturing weapons for technical analysis. They’d shadow enemy units for days, never engaging, just collecting information. By late 1966, this approach started producing results that American intelligence officers couldn’t ignore.

SAS patrols were locating enemy base camps, supply caches, and movement patterns with uncanny accuracy. Their stay behind operations remaining in areas after major American operations revealed how the VC simply waited out the Americans, then returned. One operation exemplified the difference. After a large American search and destroy sweep through suspected VC territory in November 1966 that found nothing, an Australian SAS fourman patrol inserted into the same area.

They remained for 12 days moving less than 8 km total. They photographed three VC camps, documented supply routes, identified a battalion headquarters, and called in precision strikes that destroyed months of VC logistics. All without firing a shot until their extraction. Operation Crimp, February 196, the moment everything changed.

American and Australian forces launched a major operation into the Hobo Woods, a known VC stronghold. The Americans went in loud. Helicopters, artillery prep, infantry sweeps. The Australians went in quiet. Small patrols, careful movement, eyes open. Corporal Bob Bottel of the Australian First Special Air Service Squadron, 1 SASS Quen, was leading a patrol when his point man, Trooper Danny Smith, stopped suddenly.

Hand signal. Freeze. Smith had spotted freshly turned earth that didn’t match the surroundings. What they discovered would change American understanding of the war. The Qi tunnels, not just foxholes, but an entire underground city. 200 km of tunnels complete with hospitals, weapons factories, sleeping quarters, and command centers.

The Americans had been walking over the enemy for months. But discovering tunnels and clearing them required different skills. American tunnel rats volunteered for the nightmare duty of crawling into black holes with a pistol and flashlight. The VC had every advantage. Booby traps, puny stakes, blind corners, and homefield knowledge.

The SAS approached it differently. We didn’t send men into tunnels unless absolutely necessary, recalled Sergeant Jim Weir of Three Squadron SAS. We’d map entrance points, identify ventilation shafts, then pump in CS gas and collapse strategic sections. If intelligence value was high, we’d send someone down, but never alone.

Always with backup position to extract him fast. In March 1966, an SAS patrol in Puaktui province made contact that became legendary among VC units. Fourman patrol call sign Charlie 1 was observing a trail junction when a 20man VC unit appeared. Protocol dictated break contact and evade. Instead, patrol commander Sergeant Jim Campbell made a different call.

They waited. The VC unit stopped 30 meters from their position, stacking weapons and removing packs. Rest break. Campbell’s patrol remained frozen for 43 minutes while the VC smoked, talked, and relaxed. When the VC finally moved out, Campbell’s team followed them for 2 km to their base camp, a company-sized position with weapons caches and supply stores.

That night, Campbell called in the intelligence. The next morning, Australian artillery and American air strikes obliterated the position before the VC knew they’d been compromised. 67 confirmed KIA massive weapons losses, and the VC never knew how they’d been found. But the operation that truly broke VC confidence occurred in June 1966. and says patrol led by Lieutenant John White tracked a VC unit for 5 days through Fuaktu Province.

Not following trails, actually tracking the enemy like animals, reading bent grass, disturbed leaves, and barely visible footprints. White’s patrol documented the VC unit’s movement patterns, base locations, and command structure without ever being detected. The intelligence enabled a coordinated ambush that killed the entire enemy leadership element, 17 men, including two senior commanders.

The surviving VC found notes left at the ambush site written in Vietnamese. We’ve been watching you, psychological warfare, SAS style. By August 1966, VC intelligence reports were documenting a disturbing pattern. Small enemy units were operating deep in controlled territory. They appeared and disappeared like ghosts.

They seemed to know VC movements before the VC made them. They killed silently and efficiently, often arranging bodies to send messages. A captured document from September 1966 revealed the impact. Unknown enemy forces, possibly elite American or foreign troops, have established presence in our base areas. They employ unusual tactics.

Avoid engagement if possible. Report all unusual jungle signs immediately. The Vietkong masters of jungle warfare were now afraid of their own jungle. The Vietkong’s response to SAS tactics revealed how deeply the threat had penetrated their confidence. By late 1966, VC units in areas with SAS presence implemented new security protocols that their commanders in American dominated areas didn’t bother with.

They stopped using regular trails. They doubled sentry rotations. They began random camp relocations every 3 days instead of weekly. They instituted buddy systems where no one moved alone, even for latrine calls. These measures significantly degraded their operational efficiency, which was exactly the point.

We weren’t trying to kill every VC, explained Australian SAS Captain Ron Large. We were trying to make them ineffective. A VC unit spending half its energy on security measures can’t spend it planning operations. We were winning by making them paranoid. The SAS evolved their methods, too. They developed stepup tactics where a successful ambush would be immediately followed by positioning another ambush on the logical retreat route.

VC fleeing one contact would run straight into another. Survivors of the second ambush would find a third team waiting at the next rally point. It was psychological destruction, recalled Sergeant Dave Cirten of Two Squadron SAS. After three consecutive ambushes on what should have been their safe withdrawal routes, enemy units started surrendering rather than running.

They couldn’t trust their own operational planning anymore. The British SAS advisory role expanded in 1967, bringing refinements from their Borneo operations. They introduced clarrett operations, unauthorized crossber raids that officially never happened. Small SAS teams would cross into Cambodia, target VC sanctuary areas, then fade back into Vietnam before anyone could respond.

These operations remained classified for decades, but were whispered about in VC base camps. The ghosts could cross any border. American units began requesting SAS training. The US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, MACV, established specialized courses where Australian SAS instructors taught American LRP, long range reconnaissance patrol units.

The lessons: move slower, observe more, shoot less, think like prey, pretending to be predator. Some American units adapted brilliantly. Makfisog, the covert special operations group, adopted SAS techniques wholesale. Their crossber operations into Laos and Cambodia mirrored SAS methodology. Small teams, surgical strikes, maximum intelligence value, minimum footprint.

But cultural differences persisted. American military culture rewarded aggression and contact. Body counts mattered. SAS culture rewarded intelligence and restraint. Patrols that never fired a shot but brought back actionable intelligence were celebrated. As one American LRP veteran noted, “We wanted to kill the enemy.

They wanted to understand him first, then kill him efficiently.” Totally different mindset. The VC adapted their counter tactics specifically for SAS operations. They began using decoy camps with deliberately obvious security flaws to draw in patrols. They positioned reaction forces to surround suspected observation posts.

They even deployed their own small hunter killer teams to track the trackers. It rarely worked. The VC were good, acknowledged former VC commander Guen Monten in a 1995 interview. But the SAS were different. They thought like us, moved like us, but had training and discipline we couldn’t match. Fighting Americans was fighting an army.

Fighting SAS was fighting shadows that killed. By 1968, SAS operations in Vietnam had achieved what conventional forces couldn’t, dominance in enemy controlled territory. The Ted offensive, which surprised American forces across South Vietnam, found Australian SAS squadrons ready and waiting.

They’d been reporting the buildup for weeks through their continuous patrol operations. In Fui Province, SAS patrols provided early warning that allowed Australian task force to prepare defensive positions. While American bases were overrun elsewhere, the Australians repelled attacks with minimal casualties. The difference was intelligence.

SAS teams had been watching the attack preparations develop in real time. The statistics tell part of the story. From 1966 1971, Australian SAS squadrons rotated through Vietnam with approximately 600 total personnel. They inflicted over 500 confirmed enemy KIA, captured intelligence, leading to thousands more casualties, and suffered just three killed in action.

That’s a kill ratio that defied conventional warfare mathematics. But numbers missed the psychological impact. A captured NVA officer interrogated in 1969 described his unit standing orders regarding SAS patrols. If you see them, don’t engage. report position and withdraw. They always have support nearby and they never lose.

That last part wasn’t strictly true. SAS patrols could be overwhelmed by superior numbers. But the perception was what mattered. VC and NVA units genuinely believed that engaging in SES patrol was suicide. The reality was more nuanced, but reality wasn’t what controlled behavior in the jungle. The British SAS advisory mission reached its peak effectiveness in 1968 to 1970 when their training programs had produced multiple generations of American LRP and special forces soldiers who understood jungle warfare as craft

rather than chaos. These units began producing their own successes, applying patience and observation over firepower and aggression. The SAS taught us that silence was a weapon, recalled Staff Sergeant Billy Wah, a MAC Visag operator. They showed us that watching the enemy for 3 days before attacking was better than attacking immediately.

They proved that four quiet men could accomplish what a platoon with air support couldn’t. Perhaps the ultimate measure of SAS effectiveness came from enemy action or inaction. By 1969, certain areas of Tuaku province were effectively VC free, not because of major operations, but because the VC simply abandoned them.

The cost of operating in SAS territory exceeded any strategic benefit. They couldn’t move safely, couldn’t rest securely, couldn’t plan effectively. The SAS had won without fighting, the highest form of warfare according to SunSu, and one the Vietkong understood intimately. Being beaten at their own philosophy, was a bitter pill.

The Australian SAS withdrew from Vietnam in 1971, their mission complete. They’d proven that small unit excellence, properly applied, could achieve strategic effects that massive conventional operations couldn’t. The Americans would continue their war for another four years. But the lessons had been learned, if not always applied.

Modern Special Operations Forces worldwide study SAS operations in Vietnam as masterclass examples of counterinsurgency done right. the patience, the intelligence focus, the restraint. These became doctrinal foundations for special operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and beyond. We didn’t win the Vietnam War, reflected Major General John Essex Clark, who commanded Australian SAS squadrons in Vietnam.

But we showed there was a better way to fight it. Whether anyone was listening is another question. The Vietkong learned their own lessons. Former VC fighter Truang Nu Tang wrote in his memoir. The American military was powerful but predictable. The SAS was different, patient, precise, and terrifying in their efficiency.

We feared them because they fought like we did, only better. That fear was the SAS’s greatest weapon. Not the rifles, not the training, not even the kill ratios. The fear that the jungle itself had turned against the Vietkong, that nowhere was safe, that the hunters had become the hunted. 3,000 words couldn’t fully capture what four-man patrols accomplished in the Vietnamese Highlands.

But those patrols proved a timeless truth. In unconventional warfare, the quality of soldiers matters more than quantity. Precision beats firepower. Patience conquers aggression. The Americans brought an army to Vietnam. The cess brought something more dangerous. Understanding. Understanding that winning hearts required protecting villages, not destroying them.

Understanding that intelligence mattered more than body counts. Understanding that sometimes the most powerful thing a soldier can do is watch, wait, and strike only when victory is assured. The Vietkong feared the SAS because the SAS were everything they thought they themselves were, but refined through professional training, superior discipline, and a military tradition stretching back centuries.

When masters of guerrilla warfare met soldiers who’d perfected it into an art form, fear was the only rational response.

News

They Mocked His “Backwards” Loading Method — Until His Sherman Destroyed 4 Panzers in 6 Minutes D

At 11:23 a.m. on September 19th, 1944, Private First Class Walter Kowalsski crouched inside his M4 Sherman tank near…

The Most Insane Helicopter Pilot of Vietnam – Ace Cozzalio D

Oh, good girl. You want to hear the story about the deadliest IHOP employee to have ever existed? Yeah….

Why American Soldiers Started Killing Their Own Officers in Vietnam D

Today’s video is brought to you by the good people over at AG1. I told myself I wasn’t doing…

How Canadians Stood Up for Black GIs After U.S. MPs Crossed the Line D

July 1944, Aldershot, England. The summer air hung thick and warm inside the Red Lion Pub. Canadian soldiers sat…

The Ugly Gun That Beat the Beautiful Thompson: M3 Grease Gun’s WWII Revolution D

October 1942, a General Motors Inland Division in Dayton, Ohio, George Hyde, a 52-year-old immigrant from Germany, was completely…

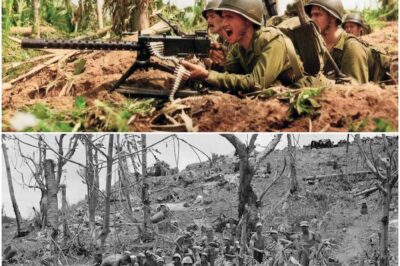

Why U.S. Marines Waited for Japan’s “Decisive” Charge — And Annihilated 2,500 Troops D

July 25th, 1944. Western Guam, Our Peninsula. A narrow strip of land barely half a mile wide, shielding the…

End of content

No more pages to load