In the summer of 1943, the Mediterranean sun was an unforgiving hammer beating down on the shores of Sicily. Among the massive wave of ships and men preparing to storm Fortress Europe, there was a particular unit that looked different from the rest. They wore a distinctive patch on their shoulders, a golden Thunderbird emlazed on a blood red square.

They were the 45th Infantry Division. To the casual observer, they were just another group of National Guard boys from the American Southwest. But to General George Patton, they were something far more dangerous. And to the German high command, they would soon become a supernatural terror that defied everything the master race believed about warfare.

You see, the 45th was unique. In 1940, when the division was federalized, approximately 2,000 of its 9,500 troops were Native American soldiers from over 50 different tribes. Cherokee, Chalkaw, Muscogee Creek, Kya, Apache, and dozens more. These were men who grew up in a country that often treated them as secondclass citizens, denied them the right to vote in many states, and forced their parents through the trauma of Indian boarding schools designed to erase their culture.

Yet here they were, crossing an ocean to fight for the very democracy that had failed to protect them. The Germans had a deep respect for Patton. They called him the closest thing America had to their own panzer generals. aggressive, lightning fast, unpredictable. But when the 45th division hit the beaches and began their advance through Sicily, Italy, and France, German field commanders began sending reports back to headquarters that sounded less like military intelligence and more like ghost stories. The Thunderbirds didn’t fight

like other American units. They moved with a terrifying silence. They appeared where they were least expected. They refused to break even under impossible odds. And at the heart of this unstoppable force were the Native American soldiers whom Patton would call one of the best, if not the best, division in the history of American arms.

Before the war began, the 45th Division had worn a swastika on their shoulder patch, an ancient Native American symbol of good luck. When the Nazis corrupted that sacred symbol, the division held a competition in 1939 and chose a new insignia designed by Kya artist Woody Bigbo, the Thunderbird. In many indigenous cultures, the Thunderbird is a supernatural being that creates thunder with the flap of its wings and lightning with the blink of its eyes, a sacred bearer of unlimited happiness and a protector against evil spirits. When those boots hit the

Sicilian sand on July 10th, 1943, the thunder followed. But before we dive in, tell me where you’re watching us from. And may God bless you wherever you are. Now, let’s begin. The Sicilian campaign was supposed to be a methodical grind. The Allies testing the soft underbelly of Europe before the real push into France.

But when the 45th Infantry Division stormed ashore at Scoliti, they moved with a speed that left German commanders bewildered. The July heat was crushing. The dust was so thick you could taste it, coating your teeth and tongue with a gritty film that mixed with the salt from the sea. The air smelled of cordite and diesel fumes, and the peculiar metallic scent that comes from freshly spilled blood baking in the sun.

The German defenders had spent months fortifying the island. They had studied the terrain, positioned their artillery, and dug in with a methodical precision that Vermont doctrine demanded. But the Thunderbirds possessed something the Germans hadn’t accounted for. An instinctive understanding of terrain that came from generations of tracking and hunting across the rugged landscapes of Oklahoma, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado.

Many of the Native American soldiers in the 45th Division had grown up reading land the way city kids read street signs. A broken branch wasn’t just a broken branch. It told you which way someone had gone and how long ago. A change in the vegetation told you where water was, where the ground was soft, where you could move without being seen.

They looked at the sunbleleached hills of Sicily not as obstacles, but as a series of opportunities, and they moved through them like water, finding the path of least resistance. One German prisoner, captured by the 180th Infantry Regiment, complained to his interrogators with genuine confusion, “Don’t you ever sleep?” The Thunderbirds had pushed through a thousand square miles of enemy territory in just 22 days, moving so relentlessly that entire German units found themselves surrounded before they realized the Americans had flanked them.

Major General Eberhard Rod, who commanded the 15th Panzer Grenade Division against the 45th, wrote in his immediate post-war report with barely concealed frustration, “The enemy conducted movements that should not have been passable.” This wasn’t just grudging respect. It was the beginning of a profound discomfort.

The Germans had built their entire military philosophy around rigid discipline and textbook maneuvers. They were encountering men who didn’t follow European rules of warfare. Men who viewed combat not as a job but as a test of ancestral spirit. As the war moved into the rugged heart of Italy in September 1943, the intensity reached a breaking point.

The 45th division landed at Serno on September 14th and within 8 days found itself locked in a vicious battle near a small village called Olivetto. The morning of September 22nd was cold and damp. The air was thick with the smell of wet wool from soden ooniforms and the acrid bite of sulfur from mortar shells that had been falling all night.

It was here that the world would learn the name Ernest Childers, a proud member of the Muscogee Creek Nation from Broken Arrow, Oklahoma. Childers was a second lieutenant, one of eight brothers who had learned to shoot with a single bullet a day hunting rabbits to feed his family during the depression. Every shot had to count because dinner depended on his skill.

On that morning, Childers learned his battalion was pinned down by murderous machine gun fire from German positions on a hilltop. The frantic rhythmic chattering of MG42 machine guns, what the Americans called Hitler’s buzzsaw, echoed across the valley at a rate of 1,200 rounds per minute. Men were dying in the open, cut down before they could find cover.

A German mortar shell exploded nearby, and Childers felt the bones in his foot shatter. The pain was immediate and blinding. The logic of most men, that would be the end of the fight. But Ernest Childers wasn’t most men. Crawling on his hands and knees through jagged rocks and cold mud, with his broken foot dragging behind him like a dead weight, Childers refused to let the pain stop him.

He organized eight men and began working his way up the hill. The smell of explosions was everywhere. That distinct combination of burning metal and chemical propellant that coats the back of your throat. When he encountered two German snipers in a nearby house, he killed them both with precise rifle fire.

Then he moved behind the first machine gun nest and killed all the occupants. At the second nest, he threw rocks into it. When the two startled Germans raised their heads to see what was happening, Childa shot one. The other was killed by one of his men. He continued up the hill and single-handedly captured an enemy mortar observer, disabling the artillery that had been reigning death on his brothers.

When he was later awarded the Medal of Honor, the first for a Native American in World War II, it sent a shock wave through both armies. To the American command, it was extraordinary bravery. To the Germans, it was evidence that they were facing something they couldn’t break with conventional terror. They were beginning to understand that for the Thunderbird soldiers, the mission was sacred, and physical pain was merely a secondary concern.

One German intelligence report from this period noted with confusion, “These soldiers do not respond to suppressing fire as expected. They advance when pinned down.” By January 1944, the 45th Division was tapped for one of the most audacious and ultimately disastrous amphibious assaults of the war, Anzio. The plan was to land behind German lines and bypass the fortified Gustav line.

Instead, the Allies found themselves trapped in a tiny pocket of land, surrounded by mountains bristling with German heavy artillery. For 76 days, the men lived in holes in the ground, unable to stand during daylight for fear of a sniper’s bullet or an artillery shell with their name on it.

This is where the 45th earned their immortal nickname, the rock of Anzio. The cold was crushing. The February rain turned everything into freezing slush. The air tasted of salt from the sea mixed with the metallic tang of blood and the sweet rotting smell of bodies that couldn’t be retrieved from no man’s land. Men developed trench foot and frostbite.

They slept in water. They ate cold rations because a cooking file would draw artillery. And through it all, they held. On February 22nd, 1944, exactly five months after Child’s heroism at Olivetto, the Germans launched Operation Fish Fang, a massive counteroffensive ordered by Hitler himself to lance the abscess of the Allied beach head.

They threw everything they had at the center of the line, the section held by the Thunderbirds. The earth literally shook for days. The sound of the barrage was so constant that men lost the ability to hear anything else. Their world became a continuous roar of explosions. It was during this desperate moment that First Lieutenant Jack C.

Montgomery, a Cherokee from Oklahoma, looked out from his position near Padalone and saw a sight that would have frozen the blood of a lesser man. Three separate groups of German infantry supported by heavy machine guns and preparing to overrun his platoon. The air was thick with diesel fumes and cordite. The ground trembled with the weight of incoming artillery.

Without waiting for orders, Montgomery grabbed his M1 rifle and several grenades. He told his men, “Cover me. I’m going forward.” And began crawling through an irrigation ditch toward the first German position. He moved with such precision that he got within grenade range before they detected him. His first throw was perfect.

Eight Germans died, four surrendered. He returned to his platoon for more grenades and ammunition, then called in artillery fire on a house where the Germans had concentrated their forces. As they fled the bombardment, he captured them. In total, he single-handedly killed 11 German soldiers and captured 32, completely dismantling a coordinated assault.

The German officers who were captured that day expressed a profound confused disbelief to their interrogators. They asked, “Who are these men with the Thunderbird patches who fight like demons and move like shadows?” The disconnect between Nazi racial theory, which taught them that non-Arians would flee at the first sight of superior German forces and the brutal reality of the 45th division’s courage, began to rot the morale of the weremocked units facing them.

They realized that the rock of Anzio wasn’t made of stone. It was made of men who considered retreat a greater wound than death. By May 1944, the stalemate at Anzio was finally breaking. The allies were pushing toward Rome, but the German Caesar line was a masterpiece of defensive engineering. Concrete bunkers, interlocking fields of fire, anti-tank ditches, and minefields.

This was the moment for Van T. Barfoot, a technical sergeant with Chuckaw heritage from Mississippi to cement the 45th Division’s reputation as the most dangerous unit in the European theater. If the Germans thought they had seen the limit of the Thunderbird’s fury, Barfoot was about to prove them dead wrong. On May 23rd, near the village of Carano, the morning was choked with a heavy artificial fog, a mix of smoke pots and the dust of a thousand falling shells.

Barfoot’s platoon was ordered to advance across a minefield under intense German crossfire. It was a suicide mission by any conventional calculation. Barfoot asked permission to move alone along the left flank. Permission granted. Using hand grenades and his Thompson submachine gun, he crawled through the minefield.

One wrong movement meant being blown to pieces and destroyed three machine gun nests. He killed at least four enemy soldiers and captured 17. His actions allowed the entire platoon to cross the minefield without being fired upon. But he wasn’t finished. Later that same day, the Germans realized they were being humiliated by a single man.

They sent three massive Mark 6 Tiger tanks to crush him. Imagine the scene. A lone man standing in an open field. The ground trembling with the weight of 56 tons of Nazi steel. Each tank armed with an 88 mm gun that could destroy any Allied tank with a single shot. The mechanical growl of the engines was like the sound of industrial death approaching.

Barfoot didn’t run. He grabbed a bazooka, took aim with hands that showed not a tremor, and from 75 yd away disabled the lead tank with his first shot. As the German crew scrambled out, he cut them down with his Thompson. The other two tanks, witnessing what had just happened, retreated in total disarray. Barfoot then moved forward into enemy held territory and destroyed an abandoned German artillery piece with demolition charges.

On his way back, exhausted beyond measure, he found two of his wounded comrades and carried them, each trip, 1700 yards, to safety. The story of Van Barfoot spread through the German ranks like wildfire of fear. Were mocked commanders began issuing tactical warnings. Do not engage the Thunderbird scouts in close quarters combat.

They realized these men possessed a cultural heritage of warfare that emphasized individual initiative and extreme personal bravery. Traits the rigid top-down German military struggled to counter. For the soldiers of the 45th, many of whom still couldn’t vote in their home states, who couldn’t eat in certain restaurants, whose parents had been forced into government boarding schools designed to destroy their culture.

Their performance on the battlefield was a silent, powerful statement. They weren’t just fighting for a flag. They were fighting for the dignity of their ancestors. They were proving that courage doesn’t belong to one race. and in the process they were making the master race tremble in their boots.

After the breakout from Anzio and the liberation of Rome, the 45th division didn’t rest. They were tapped for their fourth amphibious landing of the war, Operation Draon, the invasion of southern France in August 1944. By now, the division was a battleh hardardened lethal machine. They had survived the heat of Sicily, the mud of Salerno, and the claustrophobic hell of Anzio.

When they hit the beaches of the French Riviera, they didn’t just land. They exploded inland with a ferocity that shocked even veteran German units. The Thunderbirds moved with a speed that German logistics couldn’t match. They had developed specialized tactics for fighting in the dense forests and steep valleys of the Voj Mountains.

They used the terrain against the enemy, utilizing their natural scouting abilities to pinpoint German artillery positions before they could fire. The sound of a Thunderbird patrol in the woods became a source of psychological terror for German centuries who knew that if they heard movement, it was already too late. Native American soldiers would slip out of their foxholes at night, navigating no man’s land with such precision that they could move through German lines, leaving calling cards to unnerve the enemy, taking a Luger from a sleeping

officer’s side, cutting telephone lines, marking positions for artillery. This wasn’t just tactical reconnaissance. It was psychological warfare at its most personal level. As they pushed toward the German border, the intensity of combat reached a fever pitch. The 45th spent more days in continuous combat than almost any other unit in the United States Army.

511 days of unrelenting battle. Their uniforms were ragged. Their faces were etched with the thousand-y stare. Their ranks were thinned by constant loss. Men who had landed on the beaches of Sicily were long gone, replaced by reinforcements who had to quickly learn the Thunderbird way of fighting or die. Yet the spirit remained unbroken.

German commanders in their internal memos began referring to the 45th as Patton’s personal guard of devils. They couldn’t understand where this endless reserve of energy came from. The answer was simple yet invisible to the Nazi mind. These men were fueled by a moral clarity that their oppressors could never grasp. They were liberating a continent from a regime built on the very ideas of racial superiority that Native Americans had spent centuries resisting in their own way.

Every village they freed, every German position they overran was a blow against the ideology of hate. As they crossed the Ryan River in March 1945 and entered the heart of Germany, they weren’t just soldiers anymore. They were the harbingers of a reckoning. As the spring of 1945 began to bloom across a shattered Europe, the 45th Infantry Division drove deep into Bavaria.

They had orders to move toward a town called Dhau. To the soldiers, it was just another coordinate on a map. to history. It would become a name synonymous with the absolute limit of human depravity. On April 29th, 1945, the Thunderbirds reached the gates of Daau concentration camp. The first thing that hit them wasn’t enemy fire. It was the smell.

A thick, sweet, rotting stench that hung in the air like a physical weight. The scent of death so concentrated it seemed to stain their uniforms and skin. As the men moved closer, they found railway tracks. Dozens of coal cars filled not with fuel, but with the emaciated remains of thousands of human beings. Men, women, and children starved to the point that they looked like skeletons covered in parchment.

For the Native American soldiers of the 45th, who carried their own ancestral memories of displacement, forced marches, and systematic destruction, the site was a tectonic shift in their souls. They had seen the worst of war, bodies blown to pieces, men dying in agony from wounds that couldn’t be treated. But they had never seen the worst of humanity engineered into an industrial system.

The liberation of Daau was not a celebrated military parade. It was a scene of visceral raw emotion. Many of the battleh hardened soldiers, men who had killed in hand-to-hand combat without flinching, fell to their knees and wept openly. The Thunderbirds found the gas chambers, the crematoriums where the ovens were still warm, rooms where naked bodies were piled from floor to ceiling.

More than 30,000 prisoners barely alive, their eyes hollow with suffering that transcended language. In that moment, the German general’s fear of these soldiers was finally justified in a way they hadn’t expected. The soldiers of the 45th were no longer just combatants. They were witnesses to a crime that defied comprehension. They saw the living dead crawling toward them, reaching out with twig-like fingers to touch the Thunderbird patches on the soldiers shoulders as if touching a symbol of hope itself.

There is a long debated historical controversy about what happened in the hours after the liberation. In the chaos of that day, some SS guards were killed by liberated prisoners and according to some accounts by American soldiers overwhelmed by righteous fury. The 45th Infantry Division had spent 511 days in combat. Seeing their brothers blown to pieces for the sake of freedom, now standing amidst literal mountains of corpses, the rage was overwhelming.

They realized that every mile they had marched, every drop of blood they had spilled had been justified. They weren’t just winning a war. They were closing the gates of an underworld that the Nazis had built on Earth. The war in Europe fell silent in May 1945. The 45th Infantry Division had accomplished something extraordinary.

They had fought in four major amphibious assaults, Sicily, Salerno, Anzio, and southern France. They had spent 511 days on the front lines, more than almost any other American division. They had liberated DACA. They had produced three of the first five Native Americans to receive the Medal of Honor in the 20th century.

Ernest Childers, Jack Montgomery, and Van Baroot. But when these heroes returned to the United States, they didn’t return to a country ready to give them the equality they had earned. Ernest Childers returned to Oklahoma where he still couldn’t vote in certain counties. Jack Montgomery went back to a state where restaurants could refuse to serve him.

Van Barfoot returned to Mississippi where Jim Crow laws remained in full force. They carried the Medal of Honor around their necks, but they still had to navigate a society that struggled to see them as full citizens. Yet, they didn’t return with bitterness. They returned with a quiet, unshapable dignity. They knew what they had done.

They knew that when the world was at its darkest, when the master race stood at the height of its power, it was the Apache soldiers, the Thunderbirds, the rock of Anzio, who had held the line. They looked into the eyes of the Reich and watched them blink in terror. The irony was profound and painful.

These men had risked everything to defeat a regime that believed in racial superiority only to return to a nation that still practiced segregation and discrimination. But their legacy transcended the injustice they faced at home. The legacy of the 45th Infantry Division lives on today, not just in history books, but in the very identity of American military culture.

The German generals were right to be afraid, though perhaps not for the reasons they initially thought. They feared Patton’s tactical genius and America’s industrial might. But what truly terrified them was something they couldn’t counter with better tactics or more tanks. They were fighting men who possessed a spiritual resilience that no amount of artillery could shatter.

These soldiers proved that courage doesn’t belong to one race or one creed. It belongs to those who are willing to stand up when everyone else is kneeling. The Thunderbirds taught us that even when you were treated as an outsider in your own land, you can still be its greatest protector. General Patton called them one of the best, if not the best division in the history of American arms.

He understood what the German commanders were slowly learning through bitter experience. The 45th Division fought with a combination of modern military training and an ancient warrior tradition that emphasized honor, individual courage, and protection of the community. It was a combination the Vermacht had no doctrine to counter.

The Thunderbird, that sacred symbol chosen to replace the corrupted swastika, became a global icon of liberation. It represented the power of protecting the innocent and exacting justice on those who would prey on the weak. For the German soldiers who faced them, it became a symbol of their own mortality.

They learned that the men wearing that golden bird were not ordinary soldiers. They were the living embodiment of a spiritual force that transcended the battlefield. As we look back at the photos of those weary men, their faces etched with the dust of Italy and the horrors of Daau, we see a reflection of the best of us. We see that the hidden truths of the Second World War are often found in the stories of those who had the most to lose and the least to gain, yet gave everything anyway.

We see men who fought not just for freedom in the abstract, but for the dignity that had been denied to them and their ancestors for generations. The German general said Patton soldiers were worse than hell because they couldn’t understand a warrior who fights for a freedom he has never fully tasted. That is the true power of the Thunderbird.

It is a story of moral clarity in the face of absolute evil. It is a story of shared adversity transforming into unbreakable bonds. It is ultimately a story of triumph that transcends the battlefield and speaks to the deepest truth about human courage. We owe it to Ernest Childers, Jack Montgomery, Van Barfoot, and the thousands of other Thunderbirds, both Native American and their brothers in arms from every background, to remember their names, to honor their golden bird, and to never forget that the greatest weapon in any

war is the human spirit when it is fueled by justice. The thunder they created still echoes. The lightning they struck still illuminates the darkness. And the Thunderbird still soarses, reminding us that true courage knows no boundaries of race, religion, or nation. It belongs to those who stand firm when the storm comes, who advance when others retreat, who become the rock when the world needs something unbreakable.

That is why the German generals were right to fear them. And that is why we must never forget them.

News

They Laughed at the “Tea-Drinking Soldiers” — Until the British Showed Them How to Survive D

June 7th, 1944. Morning light cuts through the smoke drifting across Normandy’s hedgeros. Sergeant Bill Morrison of the 29th…

USS Carmick Fired 1,127 Shells In One Hour To Save Omaha Beach D

On June 6, 1944, General Omar Bradley stood aboard the cruiser Augusta 12 miles off the coast of Normandy…

Japanese Thought They Surrounded Americans — Then Marines Wiped Out 3,200 of Them in One Night D

July 25th, 1944. The Fonte Plateau, Guam. In the thick tropical darkness, 3,200 Japanese soldiers moved through the jungle…

Germany Stunned by America’s M18 57mm Recoilless—And Their Panzerfaust Was Outranged D

Vasil, Germany, March 24th, 1945 0900 hours. And Private Firstclass Donald Wagner of the 17th Airborne Division’s 513th parachute…

Germans Never Expected M18 Hellcat Tank Destroyers To Outrun Their Panzers D

September 19th, 1944. 0730 hours. Bison La Petite, Lorraine, France. The morning fog hung thick across the French countryside…

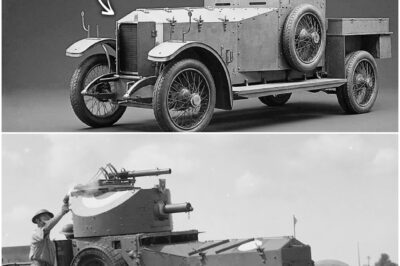

The ‘Elegant’ British Armoured Car That Fought In Two World Wars Without Becoming Obsolete D

September 1914, a shipyard in Dunkirk, Northern France. Commander Charles Rumley Samson of the Royal Naval Air Service watched…

End of content

No more pages to load