Today’s video is brought to you by the good people over at AG1. I told myself I wasn’t doing New Year’s resolutions this year, just like I do every year, [laughter] but I do like to try and just improve myself a little bit every year. And AG1 is something that has made that easier.

It’s the daily health drink with 75 ingredients, vitamins, minerals, probiotics, all the stuff I’d normally forget to take. One scoop in a jar. You shake it up. You have it once a day. It tastes great. Kind of vanillaary, pineappley. It looks really weird and green, but it does taste good. And I’ve got a bag over here. Um, this is what it comes in.

Actually, you put it in this nice tin if you’re very organized. And then on the back, it lists all of these various vitamins and minerals and good bacteria and food sourced ingredients. All of that stuff. Like I say, one scoop once a day. I’ve been using it to keep my energy steady, to not fall off my routine. It also helps your like tummy feel nice and with digestion and all of this stuff.

So, that’s good. So, if you want to try it, go to drink aag.com/intotheshadows and for a limited time, you’ll get a free AG1 duffel bag. Where’s my duffel bag, AG1? You didn’t send me a duffel bag. I want a duffel bag. I just got the stuff. And a welcome kit with your first subscription. Only while supplies last.

I imagine that duffel bag is in the post. Back to today’s episode. At 1:40 in the morning on August the 17th, 1970 in the Crangai province of South Vietnam, Captain Scott Schneder was asleep in his plywood quarters. He was 25 years old, an artillery commander, just months left on his tour. His men described him as fair and competent.

Now, he was certainly not some sort of intense disciplinarian, but by this point in the conflict, the war was going really badly. Troops were losing friends to booby traps and ambushes, and many were no longer sure why they were even there. The Inarm War, everybody. Outside the captain’s windows, someone pulled the pin on a fragmentation, the grenade.

The weapon arked through the darkness and right into Schneider’s quarters where the blast absolutely tore that hut apart. By the time the medics arrived, the young captain was dead. Investigators eventually charged one of his own enlisted men with his murder as there were no Viet Kong anywhere near the base.

Schneider was not an isolated case. Between 1969 and 1972, US records documented hundreds of deliberate attacks by American troops on their own officers and NCOs, most utilizing the same kind of grenade. This is the dark story of the Americans who killed their own officers. To understand why American troops turned on their own officers, we first need to look at the war itself by the late 1960s.

The initial optimism of the mid-60s buildup had definitely evaporated. This was not a war of liberated cities or clearly defined front lines. It was a grinding counterinsurgency fought in dense jungle defined by search and destroy missions and the grim metric of the body count. Success was not measured in miles gained, but in enemies killed, a strategy that often meant fighting for the same hill over and over again, taking heavy casualties for a terrain that would be abandoned maybe a week later.

Not exactly surprising why they were wondering why they were there. The force tasked with this strategy was overwhelmingly young and heavily conscripted. During the Vietnam era, the draft pulled in roughly 1.8 million men. The average infantryman usually just 19 or 20 years old. The war was a one-year endurance test.

You didn’t stay until the war was won. You stayed until your 365 days were up. This individual rotation system meant units were constantly churning, replacing battleh hardened veterans with terrified rookies, destroying unit cahasion before it could really even form. By 1968 and 1969, as the war dragged on and anti-war sentiment exploded back home in the US, the discipline of the US military in Vietnam began to fracture.

In June 1971, Marine Colonel Robert Dhol Jr. published a bombshell article in the Armed Forces Journal. He wrote that the morale, discipline, and battleworthiness of US armed forces were quote lower and worse than at any other time in this century and possibly in the history of the United States. and the numbers absolutely backed him up.

Desertion and unauthorized absence rates skyrocketed. In the early years of the war, desertion rates were comparable to Korea, but by 1971, the rate at 73.5 incidences per thousand soldiers, more than double the rate from the peak of the Korean War. Bases were plagued by racial violence and rampant drug use.

Historian David Cwright described this not merely as a breakdown, but as a soldiers revolt. He argued that the army was experiencing a quasi mutiny where troops were actively refusing the war through evasion, defiance, and eventually violence. And it was in this particular pressure cooker where the mission seemed pointless, the leadership seemed out of touch, and the army itself was at war with his own chain of command that fragging emerged.

And look, this wasn’t just random murder. It was the most extreme violent expression of a force that had stopped taking orders and had started fighting back. Okay, so what exactly was fragging? Well, in the grim vocabulary of the Vietnam War, the term referred to the deliberate killing or attempted killing of a fellow soldier, usually a superior officer or a non-commissioned officer.

While the word has since drifted to mean any kind of fratricside in the specific context of Vietnam, it referred to a precise and terrifying method of murder. The name was of course derived from the weapon of choice, the fragmentation grenade. specifically standard issue models like the M26, the M61, or the M67 baseballstyle grenade.

These deadly spheres were ubiquitous in combat units. They were easily acquired and easily concealed. But their popularity as tools of assassination was not just about availability. It was about anonymity. There was this cold logic to using a grenade rather than a service rifle. If a soldier shot an officer, the bullet could be recovered from the body.

Ballistics experts could examine the rifling marks on the projectile and match them to the unique barrel of the weapon issued to a specific soldier. A gunshot’s also loud, it reveals the shooter and invite someone to return fire. A grenade offered a darker alternative. It destroyed itself in the explosion, shattering into thousands of unidentifiable shards and leaving no ballistic fingerprint.

Once the pin is bowled and the spoon flies off, that’s it. There is nothing left to ID once that thing goes boom. This allowed an attacker to roll a grenade into a sleeping area, a latrine, or a command bunker under the cover of darkness and walk away before the detonation. When the dust settled, the destruction was absolute.

The chaos of the blast could easily be blamed on an enemy mortar round or a Via Kong sapper penetrating the perimeter. It provided plausible deniability in a way that just bullets can’t. This was the defining characteristic of fragging. It wasn’t the tragedy of friendly fire, which implies an accident in the heat of battle. It was calculated.

Anonymous execution carried out from within the ranks. Now, fragging definitely didn’t appear out of nowhere. While the phenomenon exploded in the early ‘7s, the first grenade began rolling into tents much earlier. As early as 1966 and 1967, isolated incidents were already being whispered about in the mess halls. But back then, they were viewed as anomalies.

Shocking individual crimes committed by unstable men rather than a symptom of systemic collapse. But that changed in 1968 because that was the year the war and the American military just kind of broke. The first hammer blow in January was the Tet offensive. North Vietnamese and Vietong forces launched a massive coordinated assault on over 100 cities and outposts across South Vietnam.

While it was a military defeat for the North, it was a psychological catastrophe [music] for the United States. It shattered the official narrative that victory was imminent. Soldiers who had been told the enemy was on the ropes suddenly found themselves fighting for their lives in the streets of Saigon. The illusion of progress evaporated, replaced by the sinking realization that this war was just unwinable.

The second blow struck just months later on April 4th, 1968. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis sent shock waves that traveled halfway around the world to those bases in Vietnam. The racial tension that was tearing American cities apart instantly bled into the barracks. For many black troops who were already being drafted and dying at disproportionate rates in the early years of the war, the killing of Dr.

King was just a breaking point. The illusion of a colorbinded brotherhood in the foxhole began to dissolve. On some bases, black soldiers wore black armbands or flew black power flags, while some white soldiers responded by openly displaying Confederate flags on jeeps. Journalist Wallace Terry, who covered black soldiers in Vietnam extensively, reported that the military began to self-segregate.

The vessels, bars, once integrated by necessity, divided into black and white zones. In the atmosphere of mutual suspicion, the authority of the officer corps, which was overwhelmingly white, was called into question like never before, radicalized by the hopelessness of the war and the racism of their own country. Some troops began to view their commanders not as leaders, but as tyrants.

And in that toxic stew of resentment, the grenade became a viable political tool. What had been a rare horror in 1966 was becoming by the end of 1968 a whispered option for settling scores. If the breakdown of discipline began in 1968, it turned into open rage in 1969. The catalyst was a battle in the Ashaw Valley fought on a mountain designated Hill 937.

But it had a rather different name among the troops, Hamburger Hill. Not because it had any hamburgers, but because that was what fighting turned men into, hamburger meat. For 10 days, the third battalion of the 187th Infantry launched repeated frontal assaults up the steep, mudslick slopes against entrenched North Vietnamese bunkers.

The fighting was close quarters and horrific. By the time the US forces finally captured the summit, 72 Americans were dead and nearly 400 were wounded. But the anger that followed wasn’t just about the casualties. It was about the futility of it all. Days after securing the peak at such a terrible cost, American commanders ordered it to be abandoned.

The troops walked away, leaving the grounds they had died for to be retaken by the enemy. What was the point? And the soldiers fury here focused on a single man, the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Welen Honeyut. Honeyut, whose call sign was Blackjack, was an aggressive officer who had pushed his men relentlessly during the assault.

In the eyes of the drafties under his command, he had traded their lives for a meaningless spot on a map to secure his own promotion. The resentment didn’t just stay in the barracks either. It went to print. You see, by this point in the war, there was a vast network of underground GI newspapers. Over 400 illicit publications.

These were not official newsletters. Definitely not. They were anti-war manifestos printed by soldiers for soldiers often hidden from the chain of command. It was one of those underground papers. GI says that a chilling offer reportedly appeared. A $10,000 bounty for the killing of Colonel Honeyut.

Adjusted for inflation, that was the equivalent of nearly $85,000 today. While there’s no record of anyone successfully claiming the reward, the threat was treated with deadly seriousness. Honeyut was well aware that he was a marked man. Veterans of the unit later recounted that the colonel had to vary his sleeping routine, never staying in the same bunker for too long, terrified that one of his own men would roll a grenade under his cot.

The Hamburger Hill bounty marked a terrifying escalation. It showed that fragging was no longer just an impulsive act of anger by a lone individual. It was becoming organized. These enlisted men were essentially crowdfunding the assassination of their own commanding officer. They were then using their own underground press to advertise it.

The message to the officer core was really, really clear. If you waste our lives, we gonna come for yours. While threats and bounties were definitely terrifying, they were often just talk. But on April the 21st, 1969, that talk turned into action at the Kong Tree Combat Base just south of the demilitarized zone.

First Lieutenant Robert T. Roella was the commander of K Company, Third Battalion, 9th Marines. By most accounts, Roella was a dedicated officer trying to keep his company functioning in a high stress environment. On that night, he was working late in his company office, essentially a semi-permanent hut with sandbag walls. The attack was brazen.

Someone approached the office in the darkness, pulled the pin on a grenade, and threw it through the door or window. The explosion devastated the small structure. Lieutenant Royer absorbed the brunt of the blast. He didn’t die immediately. He was evacuated with severe shrapnel wounds, but succumbed to his injury shortly after.

Usually, that’s where the story would end. A dead officer, a suspected enemy sapper report, and a file closed cuz there just wasn’t enough evidence. As we’ve seen, grenades don’t really leave clues. But in this case, the killer wanted credit. And to that, all I can say is don’t brag about your crimes.

I do a true crime podcast. Don’t do that. It gets you caught. Investigative focus quickly settled on Private Regginald F. Smith, a marine in Roella’s own company. According to witness testimony and investigative records, Smith hadn’t just killed his commander, he was proud of it. In the aftermath of the explosion, while the base was still in chaos, Smith was allegedly seen by his fellow Marines wearing a particular piece of jewelry.

On his finger, it was the safety pull ring of a grenade. When later confronted, Smith didn’t just rely on the code of silence. He reportedly boasted about the killing to other enlisted men in the formation, and that bravado was his undoing. While many soldiers might have sympathized with the idea of fragging, the reality of a murdered officer often broke the no snitching code, Smith was arrested and he was caught marshaled.

Faced with a testimony regarding his boasts and the physical evidence, he plead guilty to premeditated murder. He was sentenced to 40 years of hard labor, a heavy sentence, though he wouldn’t live to serve it all. Smith was killed by another inmate in prison in 1982. The Royal case is crucial because it is an exception.

It is one of the very few instances where the military justice system worked exactly as it’s designed. The crime was committed. The killer was identified and a conviction was secured. But for every Regginald Smith who was caught because he bragged, countless other attackers just kept their mouth shut, leaving investigators with nothing but a crater and a list of suspects that included an entire platoon.

If the roller case was an example of a clear-cut conviction, the attack at Benho base camp two years later illustrated just how messy and politically charged the fragging epidemic had become. On the night of March the 15th, 1971, the second battalion, 8th cavalry, First Cavalry Division, was stationed at Bienho, a massive sprawling air base near Saigon.

Around midnight, an explosion ripped through a billet housing junior officers. When the smoke cleared, two lieutenants, Thomas A. Delwo and Richard E. Harland, were dead. They’d been killed by a fragmentation grenade tossed into their sleeping quarters. Unlike in the Royal case, there was no boastful soldier flashing a grenade ring, but the army, now under intense pressure from the media and Congress to get a grip on the fragging crisis, needed a culprit.

Investigators quickly zeroed in on Private Billy Dean Smith. Smith was a 23-year-old black soldier from Watts, Los Angeles. He was not the model soldier in the eyes of his commanders. He was vocal about his opposition to the war and had a history of disciplinary friction. To the prosecution, he fit the profile of the angry, radicalized militant that terrified the brass.

To the defense, he was the perfect scapegoat. A man being targeted not because of what he did, but because of who he was and what he represented. The evidence against Smith was almost entirely circumstantial. During a sweep of the barracks after the explosion, investigators found a grenade pin in Smith’s pocket.

The prosecution argued this pin matched the lot number of the grenade used in the murder. However, the defense countered that grenade pins were common souvenirs among troops. jungle jewelry kept by grunts on their keychains or dog tags. Proving that specific pin came from the murder weapon was just scientifically impossible. The trial held in 1972 at Fort California became a sensation.

It wasn’t just a murder trial. It was a referendum on the war and race relations within the military. The defense team arguing that Smith was being framed by a racist command structure pointed to the lack of fingerprints, witnesses, or a confession. They painted a picture of a chaotic investigation desperate to pin two dead officers on a dissident black GI.

In November 1972, a jury of seven officers returned their verdict, not guilty. Billy Dean Smith, who was acquitted of the murders of lieutenants Delo and Harlon. For the army, it was a humiliating failure that proved [music] just how difficult it was to stop or even just punish fragging. You could have two dead bodies [music] and a suspect without a witness in the room or a confession.

The anonymity of the grenade just [music] won every single time. For the soldiers, it reinforced a dark reality. The barracks were a lawless zone where officers could be killed with impunity and where the justice system was seen as just another weapon in the war between the lifers and the grunts. The case of the two lieutenants remained officially unsolved, leaving a cloud of paranoia hanging over every officer billet in Vietnam.

If the breakdown of discipline provided the opportunity for franking, two other factors provided the motivation. a flood of cheap narcotics and a calendar that ticked down to zero. By 1970 and 1971, the US military in Vietnam was in the grip of [music] a drug epidemic that is hard to comprehend by modern standards. While marijuana had been common in the early years, the later stages of the war saw the arrival of number four heroin, a highly potent white powder opioid that was incredibly cheap and easily available in the villages surrounding US bases. The scale

of use was staggering. In 1971, congressional investigators estimated that 10 to 15% of US troops were addicted. Later research by psychiatric epidemiologist Lee Robbins painted an even starker picture. Her study found that 34% of soldiers had used heroin while in Vietnam and roughly 20% met the criteria for dependence.

In some units, being high wasn’t an act of rebellion. It was just the baseline state of existence for a third of the platoon. But this drug use was mixed with an even more potent psychological force, shorttimers syndrome. Because the draft mandated a one-year tour of duty, every soldier knew exactly when they were going to go home.

This date was known as DROS, date eligible for return from overseas. It became the single most important, basically religious object in a soldier’s life. Men would scratch calendars onto their helmet covers, crossing off days with black marker. As the date approached, a soldier became a short-timer. The psychology of the short-timer was dominated by a paralyzing fear of dying [music] in the final weeks or days of a tour.

A soldier with 10 months left might take risks. A soldier with 10 days left just wanted to hide. They became detached, cautious, and hyper sensitive to any threat that might stop them from getting on that freedom bird home. These two forces, addiction and the obsession with survival, created a deadly friction with the officer corp.

Many career officers or lifers tried to enforce discipline by cracking down on drug use or ordering aggressive patrols to keep the pressure on the enemy. To a heroindependent short-timer, these officers were not just annoying, they were existential threats. An officer who confiscated a soldier’s stash wasn’t just taking property, he was forcing that soldier into agonizing withdrawal in a combat zone.

An officer who ordered a search and destroy mission for a meaningless patch of jungle was seen as risking a soldier’s life for nothing more than a promotion. In this warped reality, the enemy wasn’t the Via Kong hiding in the treeine. It was the lieutenant standing in the command post. And for a soldier high on heroin, terrified of dying on a day 360 of a 365day tour, a grenade seemed like a rational way to remove the obstacles standing between him and home.

While heroin [music] and the calendar were tearing units apart from the inside, a rather different war was being fought across the color line. By the late 1960s, the US military in Vietnam had become a mirror of the fractured society that it served. The civil rights movement and the rise of black power did not stop at the Pacific Ocean.

They deployed right alongside the troops. For black soldiers, the anger began with maths. In the early years of the war, particularly around 1965 and 1966, African-Americans were drafted and assigned to combat units at rates far higher than their white counterparts. While black Americans made up roughly 11% of the US population at the time, they accounted for nearly 20% of combat deaths in the war’s early stages.

This created a bit of perception that black men were being used as cannon foder, sent to die for the country that still denied them basic rights at home. By 1969, this resentment had hardened into open defiance. On many bases, the illusion of military unity had completely collapsed. Black troops calling themselves bloods formed their own organizations with names like blacks in action or unsatisfied black soldiers.

They developed intricate handshakes known as the DAP to show solidarity. A ritual that could last for minutes and which white officers often viewed with suspicion or hostility. But the tension wasn’t just about solidarity. It was about survival. On some US bases, white soldiers openly display Confederate flags on their jeeps.

There were reports of Ku Klux Clan robes being worn in barracks and cross burnings occurring inside military compounds. For a black soldier armed with an M16, seeing a Confederate flag, the symbol of their enslavement flying over a base in Southeast Asia was just an intolerable provocation. This atmosphere was fueled by voices from Blackholm.

Leaders of the Black Panther Party and other militant groups began to explicitly urge black GIS to stop fighting the Vietnamese and start dealing with their oppressors. Some pamphlets circulated in the barracks which didn’t mince words, suggesting that if an officer was a racist, he should be fragged. The fear of a racial uprising terrified the high command.

However, the reality of fragging was more complex than just a simple race war. While the media often portrayed fragging as a crime committed by black militants against white officers, the core marshall statistics tell a really different story. According to historian George Lepre, over 50% of convicted fraggers were white. The violence was certainly fueled by racial hatred in many specific cases, but it was not exclusive to any one group.

Yet, the perception of racial violence was enough to shatter the chain of command. In many units, white officers became terrified of their black subordinates, and black troops remained convinced that their white commanders viewed their lives as expendable. In this environment of mutual terror, every order was scrutinized, and every shadow in the night was a potential threat.

The army that was supposed to be fighting communism was in many sectors too busy just fighting itself. But fragging wasn’t happening in a vacuum. It was the violent jagged edge of a much larger phenomenon that historian David Corwight later termed the soldiers revolt. By the early 1970s, the anti-war movement wasn’t just on college campuses in California or New York.

It was inside the barracks, on the aircraft carriers, and in the jungle itself. The scale of this internal resistance was just unprecedented in American history. As the war dragged on, an entire underground infrastructure emerged to support descenting troops. Soldiers produced their own media, the independent underground newspapers we mentioned earlier.

These papers typed in back rooms, printed on smuggled machines, and distributed secretly in missiles spread news of protests. Legal rights and anti-war editorials. Off base, a network of GI coffee houses sprang up near major military installations in the US. Places like Olio Strat near Fort Hood became organizing hubs where soldiers could listen to rock music, read radical literature, and meet with civilian anti-war activists away from the prying eyes of their commanders.

The Department of Defense was well aware of what was happening, and the numbers they collected were terrifying to the brass. A Pentagon study later estimated that by 1972 roughly 51% of US troops in Vietnam had engaged in some form of protest. This ranged from relatively mild like wearing peace signs on helmets or refusing to polish boots to the severe such as combat refusal, sabotage, and desertion.

It is important to make a distinction here. The vast majority of this soldiers revolt was nonviolent. Most descenting soldiers just [music] wanted to survive their tour and go home or perhaps slow down the war machine through search and avoid tactics. But fragging represented the dark extreme end of this spectrum when a unit reached its breaking point.

Fragging became a way for the enlisted men to negotiate the terms of their survival with high explosives. As socialist and writer activist Joel Guy put it later, fragging was the ransom the ground troops extracted for being used as life bait. In this context, a grenade wasn’t just a murder weapon. It was a message. It signaled to the officer core that their authority was no longer absolute.

If they pushed their men too hard or for a cause the men didn’t believe in, the war would stop being about fighting the enemy and start being about fighting for their own lives against their own troops. So, how common was this really? Was it a few isolated psychopaths, or was the officer corps being decimated? Trying to get a precise body count for the Vietnam War is difficult enough.

trying to count the murders inside the US Army is a forensics nightmare. But we do have some numbers. According to the US Army records, the trend line is undeniable. In 1969, there were at least 156 reported fragging incidents involving explosives. By 1970, that number had doubled to 321. 1971, it peaked at 363.

Now, it’s crucial to understand what instant means here. It doesn’t always mean a death. It means a grenade was thrown with intent to harm. Between 1969 and 1972, official records tally roughly 99 deaths from these attacks. However, historians and military sociologists argue that these official numbers are likely the floor, not the ceiling.

George Lepre, whose book Fragging is considered the definitive study on the subject, analyzed core marshall reviews and criminal investigative files. He estimates the total number of known and suspected explosive cases, was closer to 900. Other researchers like Richard Gabriel and Paul Savage in their book Crisis in Command push the estimate even higher.

When you include injuries and attempted attacks that failed to detonate, they suggest the total number of incidents exceeded a thousand. But we also have to be careful with the folklore. In the decades since the war, a myth has taken hold that thousands of officers were murdered by their own troops. Some internet sources claim over 1,400 mysterious deaths or imply that fragging was the leading cause of officer casualties.

These claims are exaggerated. While the breakdown in discipline was real, the officer corps was not being liquidated wholesale. If thousands of officers have been murdered, the command structure of the US Army would have just physically ceased to exist. The truth is terrifying enough. You don’t need the exaggeration. But why can’t we get a precise number? That’s because fragging lives and thrives in the fog of war.

Consider the environment. If a gray goes off during a mortar attack or a firefight, how does a coroner distinguish between an enemy explosion and an American M26 thrown by a disgruntled private? They often can’t. Many murders were likely written off as KIA because there was no way to prove otherwise.

Conversely, the statistics are skewed by definition. The army’s fragging statistics generally only tracked attacks involving explosives. If a soldier shot his left hand with a rifle, that was classified as a standard homicide, not fragging, and it went into a different filing cabinet. Ultimately, whether the true number of incidents was 800 or a,000, the statistic that matters the most is the psychological one.

It did not take a grenade in every bunk to break the army. It just took the threat of one. When every shadow could be an assassin, the trust required to lead men into battle evaporates. The grenade didn’t have to go off to do the damage. The statistics were grim, but the atmosphere on the ground was even worse.

By 1971, the fear of fragging had fundamentally altered the daily life of the American officer corps of Vietnam. The chain of command, which relies on absolute trust between leaders and subordinates, had been replaced by a state of armed paranoia. In the rear areas of fire bases, where troops should have been safe, officers and NCOs’s began taking defensive measures against their own platoon.

Many stopped sleeping in the same area as their men, moving their bunks into separate fortified bunkers, guarded by trusted staff. Others changed their sleeping routines nightly, never staying in the same bed twice in a row, terrified that a pattern would make them a target. It became common to see officers wearing sidearms in mesh halls and latrines, places that were supposedly secure because they no longer felt safe walking unarmed among their own men.

This fear had a direct impact on combat operations. To avoid becoming a target, some junior officers began to negotiate with their units. If a squad didn’t want to go on patrol, or if they wanted to avoid an area of heavy enemy activity, the lieutenant might look the other way. This evolved into a practice known as search and avoid.

Units would go out into the jungle, find a safe spot to hide for a few hours, radio in false coordinates to their superiors, and then return to base, claiming they’d made no contact. It was a tacid deal. The officer kept his men alive, and in exchange, the men didn’t kill him. The Army High Commands eventually had to acknowledge that they were losing control.

In May 1971, the Army instituted strict new controls on grenades. In many units, fragmentation grenades were confiscated and locked away in central armories, only to be issued immediately before a combat patrol and counted meticulously upon return. Commanders ordered massive shakedowns, tossing bunks and blockers in search of elicit weapons.

But the horse had already bolted. The country was a wash in explosives. soldier could buy a grenade on the black market in a nearby village for a few dollars or simply claim one was lost in combat during a firefight. When a fragging did occur, the investigation often hit a wall of silence. The Army’s Criminal Investigation Division, or C, would lock down entire units, confining hundreds of men to their barracks for days.

They fingerprinted everyone and interrogated platoon after platoon. Yet, in the vast majority of cases, they found nothing. The soldiers protected each other, bound by a code of silence that was stronger than their fear of prosecution. Even when the army did catch a perpetrator, the consequences were surprisingly light.

Because evidence was so often circumstantial, usually just a fingerprint or a witness statement without physical proof, prosecutors often had to settle for lesser charges. While some men, like Reginald Smith, received long sentences, many others convicted of manslaughter or assault served less than 10 years. The military justice system designed to maintain order found itself completely unequipped to handle a crime that was anonymous, collective, and pervasive.

Fragging was the most violent symptom of the breakdown. But it was not the only one. By 1969, the fear of officer hunting had achieved exactly what many disgruntled soldiers intended. It changed the way the war was fought. The threat of a grenade in the night became a silent veto power over tactical decisions. In the past, an infantry company would follow orders to engage the enemy regardless of the cost.

But as the war dragged on, the automatic obedience evaporated. The result was a phenomenon known as combat refusal. The most famous instance of this occurred on August the 24th, 1969 in the Song Chang Valley. Soldiers accompany a third Third Battalion, 21st Infantry, part of the 196th All Light Infantry Brigade, had been hammered by 5 days of brutal fighting.

They had taken heavy casualties and were exhausted. When the order came down to move out once again into the enemy controlled valley to retrieve bodies, the men simply sat down. A lieutenant radioed his battalion commander and delivered a message that would have been unthinkable in World War II or Korea.

I am sorry, sir, but my men refused to go. It wasn’t a panic. It was a collective strike. The refusal was witnessed by Associated Press reporter and the headline, “Sir, my men refused to go,” splashed across newspapers in the US. While the unit eventually moved out after a veteran colonel came down to talk to them, the dam had broken.

Across Vietnam, units began practicing search and avoid. We talked about it earlier. This was basically just passive mutiny. And it worked because the officers leading these platoons knew the alternative. A lieutenant who insisted on search and destroy missions, who pushed his men to walk into ambushes for terrain they didn’t care about.

It was a lieutenant who might not wake up that next morning. Colonel Robert Jr. watched this disintegration with professional horror. In his 1971 assessment, he warned that the US military was in deep trouble. He noted that while American firepower remained overwhelming, the planes could still bomb and the artillery could still shell.

The infantry, the heart of the army, was paralyzed, desertion was soaring, drug use was effectively decriminalized by commanders too afraid to enforce the rules, and on base crime was rampant. The threat of fragging had effectively neutralized the aggression of the US Army from the bottom up. By 1971, the Pentagon faced a stark reality.

They had an army of nearly a quarter million men in Vietnam, but they could no longer rely on them to actually fight. The soldiers had decided the war was over, and they were voting with their feet and occasionally with their grenades. This quasi mutiny in Vietnam forced a reckoning back in Washington. The Pentagon was facing a terrifying paradox.

They possessed the most sophisticated military technology in human history. Yet, they could no longer trust the men operating it. The citizens army model, the mass conscription system that had defeated Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, was failing catastrophically in the jungles of Southeast Asia. The answer to the fragging crisis wasn’t found in stricter grenade control or more military police.

It was found in changing the people holding the grenades. In 1970, the President’s Commission on an all volunteer armed force known as the Gates Commission delivered a landmark report recommending the end of conscription. While there were economic and political arguments for this, primarily to undercut the anti-war movement on college campuses, there was also a pragmatic military reality.

Senior commanders who had initially been skeptical of an all volunteer force began to change their minds. As they watched their units disintegrate, they realized that forcing unwilling men to fight an unpopular war didn’t just lower morale, it created a dangerous internal enemy. A drafty who felt trapped was a liability.

A volunteer who chose to be there who was a professional. On January the 27th, 1973, the same day the Paris Peace Accords was signed to end US involvement in Vietnam, Secretary of Defense Melvin Leair announced that the draft was over. The United States military shifted to an all volunteer force. Historians and military sociologists have long argued that the breakdown of discipline in Vietnam.

The drugs, the desertions, the fraggings, it was a decisive factor in this shift. The logic was cold but effective. A smaller professional army might be more expensive to pay, but it was far less likely to murder its own officers. And largely the reform worked. The fragging epidemic ended when the warded.

While there have been rare isolated instances of fratricside in modern conflicts such as the attack by Sergeant Hassan Akbar in Kuwait in 2003, they are viewed as shocking anomalies, not a systemic crisis. The culture of the US military changed. The dynamic of lifers versus drafties disappeared, replaced by a professionalized core where every soldier from the general to the private had signed on the dotted line.

The all volunteer force that exists today with its high standards of discipline and cohesion was born from the ashes of Vietnam. It is a professional institution designed in part to ensure that the chaos of 1970 where officers slept in bunkers to protect themselves from their own men would never happen again.

So when the last American combat troops left Vietnam in 1973, they left the jungles behind, but they brought the silence home with them. For decades, fragging was the war’s dirty secret. A topic whispered about in private, but rarely spoken of in VFW halls or public parades. It didn’t fit the narrative of the noble soldier or the band of brothers.

His dark, jagged memory of a time when the brotherhood broke. For the veterans who lived through it, the psychological scars run deep. In his exhaustive study, historian George Lepre examined over 500 case files and interviewed scores of veterans, including both the men who were targeted and the men who did the targeting. He found a complex landscape of [music] memory.

Some former officers admitted that they spent their post-war lives haunted by the realization that their own men had hated them enough to want them dead. They remembered the sleepless nights in command bunkers, the way conversation would stop when they walked into a messole and the ritual of shaking out their boots every morning, not to check for scorpions, but to check for a grenade pin or a booby trap.

On the other side, the perpetrators and the witnesses carried their own burdens. The pros interviews revealed a spectrum of remorse and rationalization. Some veterans looked back with profound guilt, seeing their actions as the reckless rage of traumatized young men. Others, even 40 years later, maintained that what they did was necessary, that removing a dangerous or incompetent officer was an act of self-defense that saved the lives of the rest of the platoon.

For historians and military strategists, the legacy of fragging is a stark warning [music] that echoes far beyond the Vietnam War. It serves as a reminder that military discipline is not a given. It is a fragile contract based on legitimacy. When an army loses its moral authority in the eyes of its own soldiers, when the mission seems pointless, the leadership seems indifferent, and the sacrifice seems unequal, that contract dissolves.

The soldiers revolt and the fragging epidemic with the ultimate proof that you cannot force men to fight a war that they’ve fundamentally rejected. The United States military learned this lesson the hard way. The shift to the all volunteer force and the massive professional reforms of the postvietnam era were direct responses to that collapse.

They were designed to rebuild the trust that had been shattered in the hooches of Kuang Tree and the bunkers of Hamburger Hill. Today, fragging is largely a relic of history, a ghost story from a lost war, but it remains a permanent scar on the institutional memory of the American armed forces. It stands as a testament to what happens when an army breaks and a reminder that the most dangerous enemy a soldier can face is sometimes the despair in his own ranks.

Thank you for watching.

News

Why the Viet Cong Feared the SAS More Than Any American Unit

Fuaktui Province, South Vietnam, March 17th, 1966. The Vietkong sentry never heard them coming. Nuan Vanam had survived 2…

They Mocked His “Backwards” Loading Method — Until His Sherman Destroyed 4 Panzers in 6 Minutes D

At 11:23 a.m. on September 19th, 1944, Private First Class Walter Kowalsski crouched inside his M4 Sherman tank near…

The Most Insane Helicopter Pilot of Vietnam – Ace Cozzalio D

Oh, good girl. You want to hear the story about the deadliest IHOP employee to have ever existed? Yeah….

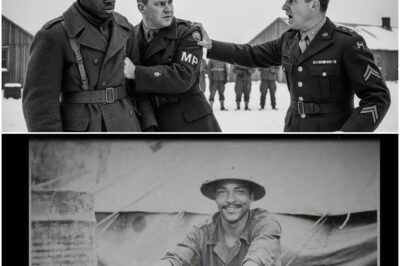

How Canadians Stood Up for Black GIs After U.S. MPs Crossed the Line D

July 1944, Aldershot, England. The summer air hung thick and warm inside the Red Lion Pub. Canadian soldiers sat…

The Ugly Gun That Beat the Beautiful Thompson: M3 Grease Gun’s WWII Revolution D

October 1942, a General Motors Inland Division in Dayton, Ohio, George Hyde, a 52-year-old immigrant from Germany, was completely…

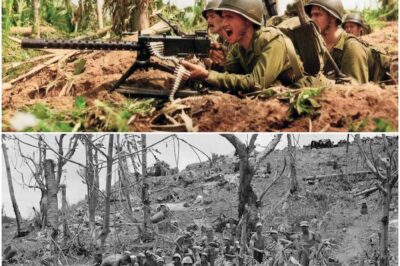

Why U.S. Marines Waited for Japan’s “Decisive” Charge — And Annihilated 2,500 Troops D

July 25th, 1944. Western Guam, Our Peninsula. A narrow strip of land barely half a mile wide, shielding the…

End of content

No more pages to load