June 7th, 1944. Morning light cuts through the smoke drifting across Normandy’s hedgeros. Sergeant Bill Morrison of the 29th Infantry Division kneels behind a stone wall, observing figures emerging through the dawn mist approximately 200 yd east. His finger hovers over his M1’s trigger momentarily. Then he notices the helmets distinctively shaped, broader brim, and the uniforms in a subtly different olive tone.

British forces moving up from Gold Beach to establish contact with American positions. Morrison had never encountered a British soldier face to face before. Neither had anyone in his squad. months of training in England, yes, but exclusively on American installations, solely alongside American units. Now, 36 hours following their assault on Omaha Beach, drained and still trembling from the landing, they’re about to encounter their allies directly.

“Hold your fire,” Morrison says quietly. “Their friendlies? Well, our allies. You understand? The British patrol advances closer. Morrison rises, extends his hand upward. The lead British soldier, identified as a lieutenant by rank insignia, halts, examines Morrison’s team, then approaches with weapon slung. Young, perhaps 23, sporting a narrow mustache and maintaining an expression of measured neutrality.

29th Infantry, the British officer inquires. His pronunciation renders the words precise, formal. Affirmative, Morrison responds. You’re advancing from Gold Beach. 51st Division, we’re establishing contact with your units near Port on Bessar. He observes the smoke columns rising toward Omaha’s direction. difficult landing yesterday.

Morrison recalls the shoreline, the casualties in the waves, the six-hour nightmare before finally clearing the beach. “Yes,” he says. “Very difficult.” The British left tenant acknowledges with a single nod, as though Morrison had verified what he’d already summised. “Understood. We’re advancing toward bio. Your headquarters aware of our position.

They are currently, Morrison says. The left tenant’s smile appears briefly, neither warm nor cold. Excellent. Proceed. He addresses his men with words Morrison cannot distinguish, and the patrol continues westward. Morrison observes their departure. His corporal Eddie Hayes from Brooklyn approaches. That’s the encounter.

That’s the British. What did you anticipate? Something more distinctive, perhaps. They resemble us. Helmets differ. Morrison observes. Uniforms vary. Notice their weapons. Leenfields. Hayes responds. My father carried one during the Great War. Claimed they’re reliable. Simply slower. Manual bolt. Morrison nods. The British navigate through the hedge with deliberate precision.

Every soldier covering another spacing immaculate movements. Professional, disciplined. They appear experienced. We’re experienced too, Hayes says, though uncertainty edges his voice. Morrison remains silent. He’s reflecting on Omaha Beach. The pandemonium and fear and frantic struggle. These British forces operate like they’re on drill.

Even now, even here, it’s distinct. He cannot determine if it’s superior or inferior. Simply distinct. By late morning, Morrison’s platoon has advanced 2 mi inland, encountering British units three additional times. Each meeting follows identical patterns. Cautious identification, concise conversation, resumption.

The British remain courteous, capable, and completely composed despite the surrounding warfare. It’s beginning to disturb the Americans. Private first class Tommy Chen, radio operator from San Francisco, articulates it during a restbait in a farmyard. They’re excessively composed, he remarks, observing a British squad preparing tea, genuinely preparing tea within a demolished barn while German artillery reverberates distantly.

Don’t they recognize we’re engaged in combat? The British have assembled a compact stove, materialize tea from somewhere, and distribute metal cups while their sergeant examines a map. One soldier smokes a pipe. A pipe implies relaxation, meditation, a peaceful Sunday. Perhaps that’s simply their nature. Morrison suggests it’s peculiar. Chen maintains.

We’re reacting to every noise and they’re conducting a tea ceremony. A British soldier, a corporal, compact and older, notices and approaches. Cup extended. Care for some? He offers, presenting the tea to Chen. Chen accepts it. Examines it dubiously. This is genuinely tea. Certainly, it’s tea. What alternative exists? Unknown. Medicine, fuel.

The British corporal chuckles. A brief sound of entertainment. You Americans and your coffee. Cannot operate without it. Correct. We’re identical with tea. Maintain steadiness. He touches his head. Calms anxiety. Chen tastes the tea. Grimaces. It’s heated. That’s precisely the intention. Morrison receives a cup when offered.

The tea is potent, acurid, unlike the sweetened iced tea his mother prepares in Virginia, but it’s warm, and the British corporal is accurate. There’s something stabilizing about it, about the ceremony of pausing, brewing, consuming, continuing. The British have fought for 5 years presently.

Perhaps this is survival after such duration. You prepare tea. You maintain patterns. You preserve humanity. How long have you been fighting? Morrison asks the corporal. Since 1940, Dunkirk, North Africa, Sicily, presently here. The corporal states it plainly without arrogance or grievance, merely reality. Yourself. 2 days.

The corporal examines Morrison’s expression, then acknowledges, “You’ll adapt or you won’t. Regardless, maintain cover and maintain your weapon.” He completes his tea, retrieves his cup, and rejoins his squad. Hayes moves closer to Morrison. Four years of warfare, and he’s preparing tea in a barn. Either they’re insane or we are.

Perhaps both, Morrison says. The contrasts become more evident as hours progress. Morrison’s platoon is assigned to a British company for an advance toward a crossroads 2 mi southward. The British captain, a tall, slender man named Payton, instructs the combined force with the identical tone Morrison’s secondary school administrator employed when clarifying disciplinary procedures.

composed, controlled, somewhat disinterested. The target is this intersection, Payton states, indicating his map. Enemy has a machine gun in placement here, possibly a mortar section here. We’ll advance in dual columns, neutralize the machine gun, and secure the position. Questions? Morrison raises his hand.

What if they have multiple machine guns? Then we’ll neutralize both. Payton responds as though this was self-evident. The critical element is maintaining formation and avoiding clustering. The enemy appreciates clustering. Simplifies their task. Morrison has numerous additional questions. What about infiladating fire? What about enemy reinforcements? What about artillery coverage? But Payton has already proceeded, delivering orders to his platoon commanders with identical, unhurried exactness.

The British soldiers observe, acknowledge, inspect their weapons with habitual competence. Nobody appears anxious. Nobody appears enthusiastic. They simply appear prepared. The American platoon commander, Lieutenant Kowalsski, approaches Morrison privately. Your assessment? I believe they have executed this previously.

Morrison states, “We have too, not identically, not 4 years continuously.” Kowalsski’s expression shows concern. “You believe we should adopt their methods?” Morrison contemplates. The British methodology is systematic, deliberate, nearly conservative. The American approach, at least according to their training, emphasizes striking powerfully and rapidly overwhelming opposition with intensity and firepower, contrasting philosophies, contrasting backgrounds.

I believe we should observe and absorb. Morrison ultimately says the advance commences at midday. The British progress forward in exemplary formation, every squad covering another, utilizing every available concealment. They advance gradually, excessively gradually, Morrison initially thinks. His impulse is to accelerate, to traverse the exposed terrain rapidly.

But the British maintain their tempo, and as they advance, Morrison begins understanding why. They never compromise themselves unnecessarily. They exploit the landscape flawlessly. When encountering opposition, they don’t assault forward. They halt, evaluate, position support weapons, and suppress the enemy location before advancing.

It resembles observing machinery function, every component coordinating with others. The German machine gun commences firing when the forward British squad reaches 50 yards from the intersection. The squad immediately seeks cover, reciprocating fire while their sergeant communicates coordinates. Within 30 seconds, a British mortar section has calculated the position.

Three rounds subsequently, the machine gun ceases firing. Advance. Payton commands and the British resume forward movement. Identical tempo, identical precision. Morrison’s squad follows, attempting to replicate the British cadence. It feels unnatural. Morrison desires to sprint to reach concealment rapidly, but he compels himself to maintain the British pace.

Hayes beside him breathes heavily. This requires excessive time, he whispers. But we’re avoiding casualties, Morrison notes. They reach the intersection 15 minutes subsequently. The German position is evacuated. The crew having withdrawn when mortars located them. The British immediately establish defensive positions, deploy patrols, and establish a perimeter.

No celebration, no relief, simply the subsequent task. Payton locates Morrison. Your men performed adequately. Commendable fire discipline. We followed your example, Morrison admits. Sensible. You’ll establish your own methodology eventually. Everyone does. Payton produces a cigarette case, genuine silver engraved, and offers one to Morrison.

The essential element is surviving sufficiently long to establish that methodology. Morrison accepts the cigarette. Is it always this disciplined for you, this controlled? Good Lord, no. Sometimes it’s absolute chaos, but you attempt maintaining structure regardless. Provides the men something to maintain. Payton ignites both their cigarettes.

You chaps crossed at Omaha. Yes, sir. heard it was rather severe. Worse than ours. It was severe, Morrison says, and doesn’t elaborate. Payton acknowledges, doesn’t pressure. Well, you’re here presently. That’s what matters. He examines his time piece. Morrison notices it’s a pocket watch, not a wristwatch. We are maintaining this position until darkness, then advancing another mile.

Your lieutenants coordinating with my executive officer. Get your men fed and rested. Morrison salutes. The British return salutes differently. He notices more casual, nearly a gesture, and returns to his squad. They’ve located a shell crater and are distributing rations. Hayes has obtained a British ration container from somewhere and is examining it with scientific curiosity.

It contains tea. Hayes announces the ration includes tea, not coffee. Tea? Naturally, it does. Chen says probably contains crumpets, too. What’s a crumpet? Unknown. Something British. Morrison sits down, retrieves his own rations. The British soldiers nearby are consuming their own meals, conversing quietly among themselves.

Their conversation differs from American banter, more understated, filled with dry humor and references Morrison doesn’t comprehend. One of them is reading a book. Actually, reading while eating. Morrison cannot imagine being sufficiently calm to read in a combat zone. A British private notices Morrison observing and approaches holding his ration tin.

Fancy a swap? I’ll trade you my tinned beef for your What is that? Spam, Morrison says. Spam, the British soldier repeats as if tasting the word. What’s it made of? Mystery meat. Ah, same as ours. Then the soldier sits down uninvited, produces a cigarette, and lights it. You lot did well today. First time working with us.

First time seeing you, Morrison says. Really? Thought you’d been training in England. We were, but we never actually encountered any British soldiers. Just trained on our own installations. The British private considers this. That’s mad. We’re supposed to be allies and they kept us separated. What did they think would happen when we met? We’d start fighting each other.

Maybe they thought we’d be too different. Hayes suggests. Are we? The British soldier asks. Different? Morrison thinks about it. Yes, but not in bad ways, just different. Well, that’s all right, then. The British private stands, brushes off his battle dress. Name’s Regge, by the way. Reg Cooper, Sheffield.

Bill Morrison, Virginia. Virginia. That’s in the South, isn’t it? You grow tobacco there. Some places. Yes. Well, Bill Morrison from Virginia, try not to get shot. I’d hate to lose a new friend so quickly. Reg wanders back to his own squad, leaving Morrison slightly confused about whether they’re actually friends or if that was just British humor. He was odd, Chen says.

They’re all odd, Hayes adds, but in a positive way. I think Morrison isn’t certain about positive or negative, but he’s beginning to comprehend that the British have their own warfare methods, their own survival techniques, and it functions for them. It might not function for Americans. It probably wouldn’t, but it deserves respect.

The evening brings additional contact between American and British forces as units consolidate positions and establish defensive lines for the night. Morrison’s platoon is positioned alongside a British platoon in a hedgero position overlooking a valley. The British immediately begin improving the position, digging deeper, establishing fields of fire, organizing watchd duty rotation.

The Americans, exhausted from two days of combat, mostly just collapse and attempt to rest. The British platoon sergeant, a man named Davies, with a Welsh accent so thick Morrison can barely understand him, approaches after dark. “Your lads look knackered,” he says to Lieutenant Kowalsski. “We are knackered,” Kowalsski admits.

Whatever that means. Tired, exhausted, done in. Davis squats beside them. When did you last sleep proper before we got on the boats? Two days ago. Davis whistles softly. Right. Here’s what we’ll do. My lads will take first watch. We’re used to it. Your boys sleep until midnight. Then we swap. Fair. Kowalsski hesitates.

You sure? That’s a lot of watch duty for your men. They can handle it. Besides, you’re no good to anyone if you’re falling asleep on watch. Davis stands. Get some kip. We’ll wake you if Jerry shows up. Morrison wants to protest. It feels wrong letting the British pull their weight, but he’s too tired to argue.

He finds a spot against the hedge, wraps his jacket around himself, and is asleep within minutes. He wakes to someone shaking his shoulder. It’s still dark. Reg Cooper is crouched beside him. Midnight, your watch. Morrison sits up, groggy. Anything happen? Quiet as church. Jerry’s probably as tired as you lot. Reg hands him a canteen tea.

Still hot. Well, warmish. Morrison drinks. The tea is sweet this time with condensed milk. It cuts through the fog in his head. Thanks. No worries. Your mate’s on watch at that gap there. Rege points to Hayes’s position. We’ve got the left flank covered. Anything moves in that valley, we’ll see it. He starts to leave, then turns back.

Oh, and Morrison, your snoring could wake the dead. Might want to work on that. Morrison spends his watch studying the British positions. Even in darkness, even with half the platoon asleep, they maintain discipline. The centuries stay alert, move regularly to avoid falling asleep, communicate with hand signals.

When Davies makes his rounds, he stops to talk quietly with each sentry, checking not just their alertness, but their state of mind. It’s professional in a way that goes beyond training, its habit, routine, the accumulated wisdom of years at war. Dawn comes cold and gray. The British are already up, brewing tea, cleaning weapons, preparing for the day.

The Americans struggle awake, stiff and sore. Morrison notices the difference in morning routines. The Americans are informal, chaotic. Everyone doing their own thing, grabbing food when they can, checking weapons haphazardly. The British are structured tea first, always tea first, then weapons maintenance, then breakfast, then equipment check.

It’s the same every morning, Davis explains. Routine kept you sane. Don’t you ever just want to sleep in? Chen asks, watching the British go through their morning ritual. Sleep in and get killed, Davis says cheerfully. Jerry loves a lazy morning. attacks at dawn, he does every time. So, we’re up before dawn, ready for him.

Disappoints him terribly. The day brings new challenges and new observations. Morrison’s platoon is attached to a British company for a clearing operation through a series of farms. The British captain, different from Payton, this one named Ashford, briefs them on the plan. It’s complex, involving multiple phases. precise timing and careful coordination.

The Americans are used to simpler plans. Go there, take that, hold it. The British approach is more elaborate. Is it always this complicated? Kowalsski asks, “This is simple,” Ashford says. “You should see a proper setpiece attack. Pages of orders, dozens of units, artillery timed down to the minute. He sees Kowalsski’s expression.

Don’t worry, you’ll get used to it or you’ll develop your own style. Americans usually do. The operation begins at 0800 hours. The British move through the farms with methodical precision, clearing each building, checking each field, moving in bounds. The Americans, assigned to the right flank, try to match the pace, but keep wanting to move faster.

Morrison finds himself constantly having to slow his squad down. Match the British rhythm. [groaning] Why are we going so slow? Hayes complains. We could be done by now. Because they want to be alive when they’re done, Morrison says. Watch them. They don’t take chances. It’s true. The British assume every building is defended. Every hedger holds an ambush.

Every gate is booby trapped. They check everything, clear everything, secure everything before moving on. It’s slow, but by the time they’d cleared the farms, they’d found three German positions that would have caught a faster moving force by surprise. During a break, Morrison talks with a British left tenant named Thornton, a young officer who’d been at Dunkirk as a private and worked his way up through the ranks.

“How do you stay patient?” Morrison asks. “How do you move this slow without going crazy?” Thornton smiles. It’s not slow to us. It’s thorough. There’s a difference. He lights a cigarette. In 1940, we moved fast. Tried to match the Germans pace. Got our asses handed to us at Dunkirk. After that, we learned you can’t outger German the Germans at Blitz Creek, but you can be more careful, more methodical, more professional.

That’s our advantage now. Doesn’t it frustrate you being so careful? Frustration gets you killed, Thornton says. Patience keeps you alive. We’ve lost enough men learning that lesson. I’d rather you chaps learned it from watching us than from your own casualties. Morrison thinks about Omaha Beach, about the men who’d rushed forward and been cut down, about the chaos and confusion.

Maybe you’re right. Of course I’m right. I’m British. We’re always right. Thornton grins. That’s a joke, by the way. We’re not always right, but we’ve been doing this longer than you, so we’ve made more mistakes and learned more lessons. Take what works for you. Ignore the rest.

By midafternoon, the farms are cleared. The British have captured 12 German soldiers without losing a single man. The Americans have learned something about patience, about thoroughess, about the British way of war. It isn’t exciting. It isn’t glorious, but it works. That evening, Morrison’s platoon shares a bivowak with a British platoon in a captured German position.

The British immediately begin improving the position. Typical. While the Americans collapse, also typical. But this time, some of the Americans help with the improvements. Having learned that the British habit of constant preparation isn’t paranoia, but survival instinct. The British break out their rations, and this time the Americans and British mix together, sharing food and stories.

Hayes trades his chocolate for British tinned pudding. Chen gets a British soldier to explain cricket. understands nothing but appreciates the effort. Morrison finds himself talking with Davies about pre-war life, about families, about what they’ll do after the war. You married? Davies asks. Engaged girl back home in Richmond.

Wife and two kids in Cardiff. Haven’t seen them in 3 years. Davies pulls out a battered photograph. Shows Morrison a woman and two children smiling. Wars hard on families. You think it’ll end soon. Davis looks at the darkening sky. We’re in France now. That’s something. But Jerry’s not beaten yet. Long way to Berlin. He puts the photograph away carefully.

But we’ll get there. You lot and us together. We’re good at different things, but together we’re strong. What are we good at? Morrison asks. You aggression, speed, firepower. You hit hard and fast. We’re good at holding, at defending, at the slow grind. Different strengths. Davies smiles. means Jerry has to deal with both styles. Keeps him confused.

A British soldier starts singing. Some music hall song Morrison doesn’t recognize and others join in. The Americans listen, amused by the lyrics about a lady from Brighton and her unfortunate choice of hat. Then Hayes starts singing something American, and the British listen with equal amusement. Neither group understands the other’s songs, but somehow it doesn’t matter.

Reg Cooper comes over, sits down beside Morrison. You lot are all right, he says. Bit loud, bit chaotic, but all right. You’re not so bad yourselves, Morrison says. Bit too fond of tea. Bit too calm under fire, but not bad. Too calm under fire. Is there such a thing? When you’re brewing tea while someone’s shooting at you? Yeah, there’s such a thing.

Reg laughs. Fair point. But the tea helps. I’m telling you. Keeps you human. Reminds you there’s a world beyond the war. He pulls out his cigarettes. Offers one to Morrison. You know what I think? I think you Yanks will win this war for us. You’ve got the numbers, the equipment, the spirit. But I think we’ll teach you how to survive it. Fair trade.

Morrison takes the cigarette, lets Reg light it. Fair trade, he agrees. The next morning brings orders to move out. The British are heading east toward Khn, the Americans west toward Sherborg. The alliance is splitting up, each force moving to its own objectives. Morrison’s platoon lines up to move out, and the British platoon they’d spent two days with comes over to say goodbye.

Davis shakes hands with Kowalsski. Good luck, Lieutenant. Keep your head down. You too, Sergeant. Reg finds Morrison, hands him something wrapped in paper for the road. Morrison unwraps it. Tea. A full tin of British Army tea. I don’t know how to make it. You’ll figure it out. Hot water, tea, bit of milk if you’ve got it, bit of sugar if you’re lucky.

Drink it when things get rough. Reminds you you’re still human. Re sticks out his hand. See you in Berlin, Morrison. Morrison shakes his hand. See you in Berlin, Cooper. The two forces move out in different directions. Morrison looks back once, sees the British disappearing into the hedge, moving with that same careful precision he’d come to recognize.

Different from Americans, different style, different pace, different approach, but effective, professional, worthy of respect. Hayes comes up beside him. You think we’ll see them again? Maybe. This is a big war, but it’s a small front. Paths cross. I hope so. I was starting to like them. Even the tea. Morrison smiles. Even the tea.

They march west toward their own objectives, their own battles. But Morrison carries that tin of tea in his pack. And 3 weeks later, when his platoon is pinned down in a village south of Sherborg, exhausted and scared, he breaks it out and makes tea for his squad. It’s terrible. He doesn’t know what he’s doing, but it helps.

It reminds them they’re still human, still alive, still fighting. And when they finally take the village and find British supplies in a captured German depot, Morrison smiles at the cases of tea stacked in the corner. Different armies, different styles, but some things are universal. The British need their tea, the Americans need their coffee, and both need each other to win this war.

The observations American troops made about British forces in those first days after D-Day were varied and complex. Some Americans found the British too slow, too cautious, too bound by procedure. Others admired their professionalism, their composure, their experience. Most fell somewhere in between, recognizing that the British way of war was different, but not wrong, effective in its own context, worthy of study, if not imitation.

The British, for their part, found Americans aggressive, informal, and sometimes reckless. But they also recognized American energy, American optimism, American willingness to learn. The two forces were different products of different military cultures and different war experiences, but they learned to work together to complement each other’s strengths to cover each other’s weaknesses.

In letters home, American soldiers described their British allies with a mixture of beusement and respect. They wrote about the tea, always the tea. They wrote about British calmness under fire, British discipline, British dry humor. They wrote about tactical differences, equipment differences, cultural differences.

But mostly they wrote about discovering that despite all the differences, they were on the same side, fighting the same enemy, working toward the same goal. One soldier from the 29th Infantry Division wrote to his sister in July 1944. The British are strange fellows. They drink tea when they should be drinking coffee.

They’re calm when they should be scared, and they move slow when they should move fast. But they’ve been fighting this war for 5 years, and they’re still here, still fighting, still professional. I guess they must be doing something right. We could learn from them. I think we are learning from them. Another American soldier, a left tenant from the fourth infantry division wrote in his diary.

Linked up with British forces today near Cararantan. Expected them to be stuffy and formal like in the movies. Some are, but most are just soldiers like us, trying to survive, trying to do their job, trying to get home. They have their ways, we have ours. Both work. That’s what matters. The relationship between American and British forces in Normandy was not always smooth.

There were disagreements about tactics, about strategy, about who should get credit for victories and who should bear blame for setbacks. There was friction between different command styles, different operational tempos, different military cultures. But beneath the friction was mutual respect, born from shared hardship and common purpose.

The British had been at war since 1939. They had fought in France, in North Africa, in Italy. They had survived the Blitz, endured Dunkirk, learned hard lessons about modern warfare. They brought experience, professionalism, and hard one wisdom to the Alliance. The Americans brought fresh energy, massive industrial capacity, and aggressive optimism.

They were new to the war in Europe, but they learned quickly, adapted rapidly, and brought resources the British desperately needed. Together, they formed an alliance that would drive across France into Germany and ultimately to victory. The initial meetings in Normandy, the first observations and impressions, were the foundation of that partnership.

American troops saw British troops and found them different but worthy. British troops saw American troops and found them inexperienced but promising. Both sides learned from each other, adapted to each other, and fought alongside each other for the next 11 months until Germany’s surrender. Morrison carried that tin of tea through France into Belgium, across the Rine, and finally to a small town in Bavaria where his unit met the end of the war.

He never did learn to make it properly. It was always too strong or too weak, too bitter or too bland. But he kept making it anyway. Kept drinking it. Kept remembering those first days after D-Day when he’d learned that allies could be different and still be allies. That respect didn’t require similarity.

That the British way and the American way could both lead to the same destination. On May 8th, 1945, when news of Germany’s surrender reached his unit, Morrison made one last pot of tea. His squad gathered around, accepted their cups without complaint. They’d gotten used to it by then. They drank a toast of victory. It was terrible tea. Truly awful. But it meant something.

It meant they’d survived. It meant they’d learned. It meant they’d fought alongside the British and come out the other side. To the British, Morrison said, raising his cup. To the British, his squad echoed. They drank, grimaced at the taste, and laughed. Somewhere in England, British soldiers were probably making their own tea, probably making it properly, probably toasting the Americans with the same mixture of affection and exasperation that the Americans felt for them.

Different armies, different styles, same victory. That’s what American troops said when they saw British troops at D-Day. They said the British were strange, formal, calm, professional, teaobsessed, and [clears throat] effective. They said the British moved too slow and thought too much and never seemed scared. They said the British had been at war too long, and it showed in their caution, their thoroughess, their refusal to take unnecessary risks.

But mostly they said the British were good soldiers, good allies, good men to have beside you in a fight. And that in the end was all that mattered.

News

Why the Viet Cong Feared the SAS More Than Any American Unit

Fuaktui Province, South Vietnam, March 17th, 1966. The Vietkong sentry never heard them coming. Nuan Vanam had survived 2…

They Mocked His “Backwards” Loading Method — Until His Sherman Destroyed 4 Panzers in 6 Minutes D

At 11:23 a.m. on September 19th, 1944, Private First Class Walter Kowalsski crouched inside his M4 Sherman tank near…

The Most Insane Helicopter Pilot of Vietnam – Ace Cozzalio D

Oh, good girl. You want to hear the story about the deadliest IHOP employee to have ever existed? Yeah….

Why American Soldiers Started Killing Their Own Officers in Vietnam D

Today’s video is brought to you by the good people over at AG1. I told myself I wasn’t doing…

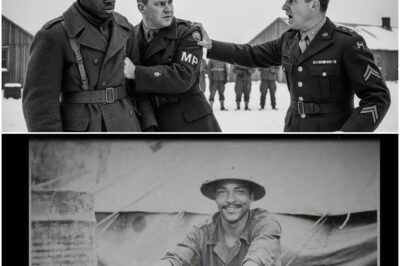

How Canadians Stood Up for Black GIs After U.S. MPs Crossed the Line D

July 1944, Aldershot, England. The summer air hung thick and warm inside the Red Lion Pub. Canadian soldiers sat…

The Ugly Gun That Beat the Beautiful Thompson: M3 Grease Gun’s WWII Revolution D

October 1942, a General Motors Inland Division in Dayton, Ohio, George Hyde, a 52-year-old immigrant from Germany, was completely…

End of content

No more pages to load