October 1942, a General Motors Inland Division in Dayton, Ohio, George Hyde, a 52-year-old immigrant from Germany, was completely absorbed by a blueprint. It detailed specs for a submachine gun that seemed next to impossible to create. The Thompson submachine gun, often called the Tommy gun, was the go-to weapon for American soldiers.

But it had a major problem. It cost $200 a piece. In today’s money, that’s over $10,000. More than four months pay for your average GI. With America sending millions of troops to fight in Europe and the Pacific, that price simply wasn’t going to work. At that cost, the US military couldn’t afford to equip its own army. Colonel Renee Studler gave Hyde a tough assignment.

Make a submachine gun that works just as well as the Thompson, but costs 90% less. And he had only 7 months to do it. American forces were scheduled to land in Sicily and Italy and would need a huge number of these weapons, way more than factories could currently produce. Hyde got to work and his first version seemed like it had potential.

But when he showed it to the officers at Aberdine proving ground, the reaction wasn’t great. One officer remarked, “It looks like something that fell off the line at a Buick factory. Where’s the normal craftsmanship? Where’s the woodstock?” The army wanted something cheap, sure, but they still wanted it to look like a proper gun.

What they ended up with was later called the ugliest weapon in American history. But out in the field, fighting in places like Italy and Korea, soldiers would come to appreciate something more important than looks. How well it could keep them alive. The morning of October 15th, 1942, found George Hyde at his drafting table in the brightly lit engineering area of General Motors Inland Division.

He’d spent 20 years designing weapons, but nothing could have prepared him for the task in the folder that Colonel Renee Studler had given him 3 days before. The document described specs that seemed mathematically impossible, but were hidden behind official language. The Thompson M1928A1 submachine gun was a sign of American power from city streets to the battlefields of Guadal Canal.

But its price made the accountant sweat, $200 per gun. In 1939, Hyde recalculated the numbers, hoping he’d made a mistake. That was around $10,500 in today’s money, more than 4 months salary for a simple soldier. Even the M1 Thompson, a version that was rushed into production after the attack on Pearl Harbor, still cost $70.

That wasn’t much better when you considered the scale of the war. The numbers were harsh. America needed to equip millions of soldiers for battles in both Europe and the Pacific. At $200 per weapon, just equipping a million soldiers would cost $200 million, almost 10% of the entire defense budget. And that didn’t even include ammunition, training, or getting the weapons where they needed to be.

The Treasury Department was clear. The Thompson was too expensive. Studler’s assignment was like a punch in the gut to hide. Design a submachine gun that worked like a Thompson, but cost 90% less. It had to be all metal. Use 045 caliber ACP rounds, fire less than 500 rounds per minute, and hit a 6×6 ft target nine out of 10 times at 50 yards.

Most important, it had to be made using methods that automotive factories could use with very little machining. Traditional gun makers laughed at this, but car manufacturers were nervous. The timeline was even tighter than the specs. Hyde had just 30 weeks before American troops would need huge amounts of submachine guns for the planned invasions of Sicily and Italy.

Intelligence reports showed that German and Italian forces were building strong defenses, which would lead to a lot of close quarters fighting. Every day that American factories couldn’t produce enough cheap submachine guns was another day that American soldiers would face enemies with better, more costly weapons.

Hyde’s first thought was to use what his team had learned from making the Liberator pistol. GM’s inland division had just finished making a million of these singleshot pistols for resistance fighters in Europe. These basic weapons were made entirely of stamped metal parts using car making tools and welding. If they could mass-produce pistols like car parts, maybe they could do the same with submachine guns.

The first model, called the T-15, was very different from traditional guns. The Thompson used carefully made steel and polished wood. The T15 was made of stamped and welded steel sheets that looked simple and functional. It had a sliding wire stock that could change the length from 29.8 in to 22.8 in. The receiver looked like two car fender pieces welded together because that’s basically what it was.

Early tests at GM’s testing range looked good. The T15 fired well, worked without problems, and could be taken apart for cleaning in less than half a minute. Most importantly, they thought it would cost less than $25 to make each one exactly the 90% cut that Stler wanted. Hyde felt a little hopeful as he prepared to show it to Aberdine Proving Ground.

The drive to Aberdeene in November felt important. Hyde knew that his model was more than just about saving money. It was about whether the army would accept something radically different or stick to traditional ideas of what a weapon should look like, no matter how practical it was. The answer came quickly and was not good. The officers at Aberdine didn’t even try to hide their dislike for the T-15.

Major William Harrison, Aberdine’s main guy for testing small arms, said, “It looks like something that fell off the line at a Buick plant. Where’s the craftsmanship? Where’s the wood? This looks more like a tool than a gun.” The problem was more than just looks. For many years, the American military thought that a weapon’s quality was tied to how well it was made with machine steel, fitted wood, and polished surfaces.

The Thompson’s look, with its drum magazine, and attention to detail, was tied to American military identity. Officers who had carried Thompsons in World War I saw Hyde’s stamped metal gun as an insult to military history. Hyde watched as his months of work were dismissed in minutes. The army said they wanted something cheap, but their reaction showed that they also wanted it to look like a real gun.

The T15 worked well, but it didn’t look the way they thought it should. The drive back to Dayton that night was cold and filled with news from North Africa about problems with the Thompson in the desert. It was ironic because the fancy Thompson was failing when it mattered most. Yet, the army was more concerned with keeping its old-fashioned look.

Every day that factories struggled to make enough Thompsons was another day that American soldiers might be short on weapons in combat. As GM’s inland division came into view, Hyde had a choice to make. He could change his design to please the army traditionalists, or he could give American soldiers what they needed to survive, no matter what anyone thought.

The Thompson’s beauty was killing it just as surely as enemy fire. And Hyde had the plans for its ugly but practical replacement. Hyde went back to his drafting table with a new idea that would change how America made small arms. What if being ugly was actually a good thing? The rejection from Aberdine hurt, but it also made him realize something important about military buying habits.

The army’s focus on looks was keeping them from seeing what was functionally better. If he couldn’t make his weapon look traditional, he would make it so effective that how it looked wouldn’t matter. Working with Frederick Samson, GM’s lead engineer and an expert in automotive mass production, Hyde began taking apart everything the military thought was important in a submachine gun.

Samson had 30 years of experience turning steel into reliable car parts. He knew that efficient manufacturing meant getting rid of anything that didn’t help the core function. Where traditional gun makers saw craftsmanship, Samson saw waste. The new model called the T20 was even more different than before. Hyde removed anything that was only there for looks, keeping only the parts that made it better in battle.

It looked rough compared to traditional guns, but was a masterpiece of practical engineering. It would soon be called the grease gun like the common automotive tool. The receiver design showed Hyde’s changed thinking. Instead of machining a solid steel block like the Thompson, the T20 used two pressed steel clamshells welded together.

Each half could be stamped from sheet steel in seconds using existing car making tools. The welding perfected for car bodies made joints stronger than traditional methods and eliminated hours of careful work. It cost $2.50 to make the receiver assembly compared to $15 for the Thompson’s machine part. The stock was another example of function over form.

Instead of the Thompson’s carefully fitted wood, the T20 used a wireframe that could slide from 29.8 in to 22.8 in. This got rid of the need for expensive materials and made it easier for tank crews and paratroopers to carry in tight spaces. It cost 30 cents per unit versus $8 for the Thompsons with stock.

Hyde’s most controversial idea was the dust cover safety system, which replaced the Thompson’s complex safeties with something simple. Flip the cover open to fire, close it to safe. It protected the weapon and was easy to use. Traditional officers thought it was too simple, but Hyde knew that being effective in combat was more important than being fancy.

The bolt design showed that Hyde understood what soldiers needed in battle. The T20’s heavy bolt fired at 450 rounds per minute. compared to the Thompson’s 700 plus. Some thought this was worse, but Hyde had studied reports from North Africa and the Pacific and knew that a slower rate meant soldiers wasted less ammunition and could control the weapon better.

American soldiers were wasting ammo with the Thompson because it fired too fast, making accurate fire almost impossible. The enclosed action was perhaps Hyde’s best idea. Unlike the Thompson, the T20’s bolt and springs were completely inside the receiver. dirt, mud, sand, and water. The soldiers constant enemies couldn’t get inside and cause jams.

This one design choice would be important in places from the mountains of Italy to the jungles of the Pacific. When Aberdine Proving Ground tested the T20 in December 1942, the results were clear. In mud tests designed to simulate combat, the Thompson jammed after 50 rounds and needed to be cleaned to work again. The T20 fired 200 rounds without stopping, proving that its enclosed action was better than traditional designs.

Sand testing was even more dramatic. The Thompson needed cleaning every 100 rounds in desert conditions, which matched reports from North Africa. The T20 kept firing for 500 rounds without maintenance. Its simple design and enclosed parts were better than the Thompson’s more complex design. Cold weather testing showed that Hyde’s approach was correct.

At temperatures that simulated European winters, the Thompson’s springs and complex action started failing as lubricants thickened and metal shrank. The T20s fewer parts and simple design kept working reliably, which would prove important during the battle of the bulge. The results were overwhelming.

In all conditions, the T20 worked 99.7% of the time compared to the Thompson’s 86.3%. The ugly gun wasn’t just cheaper. It was more reliable when soldiers lives depended on it. On Christmas Eve 1942, the military officially recommended Hyde’s T20 as the United States submachine gun, caliber.45 M3. The final cost was $18.36 for the gun plus $2.

58 for the bolt assembly. The total was $20.94, less than half the price of the Thompson, and it was more reliable. The recommendation was more than just about saving money. It was a shift in American military thinking from valuing looks to valuing practicality. Hyde’s ugly gun had proven that effectiveness, not elegance, should decide what weapons were chosen.

The question now was whether American soldiers would accept a weapon that looked like a tool but worked like the most reliable submachine gun ever made. General Motors Guide Lamp Division in Anderson, Indiana, had spent the last 10 years making car headlights. By January 1943, that same factory was undergoing a big industrial change.

As engineers changed the assembly lines to produce weapons, it was clear that American manufacturing could adapt quickly when it needed to. The M3’s design was a manufacturing breakthrough. Where the Thompson needed 21 machine parts that required skilled workers and expensive equipment, the M3 only needed three.

Everything else could be stamped, pressed, welded, or formed using existing car making tools. The receiver used the same welding methods used for car bodies, creating joints that were stronger and more consistent than traditional gunsmithing. making each magazine went from 45 minutes to under three minutes. Even the sights were simple.

The M3 used stamped metal sights that were adjusted during testing, allowing each weapon to be aimed quickly without expensive fitting. They looked rough, but were better than more elaborate designs that needed careful adjustment and maintenance. Guide Lamp could produce 1,000 cub me submachine guns per day compared to 50 Thompsons from traditional gun facilities.

It took only 30 minutes to change from headlight production to submachine gun production. Workers needed only 2 weeks of training for M3 assembly as they already understood stamping, welding, and assembly line techniques. Each M3 required 3 12 lb of steel compared to 8 12 lb for a Thompson, which was important when America was building the world’s largest military.

The reduced material wasn’t because it was weaker, but because it was designed well. The M3 stamp receiver was actually stronger than the Thompson’s machine receiver in important areas and weighed less. The first M3 grease gun came off the Anderson assembly line on May 7th, 1943, exactly 7 months and 3 weeks from Hyde’s original assignment.

The weapon was a win for American industry. Frederick Samson watched that first gun come off the line. proud to have proven that car making techniques could produce military equipment that was better than traditional methods and cost much less. But the revolution in manufacturing was about to run into the problem of military culture.

When the first M3 submachine guns arrived at training camps in the summer of 1943, they were not wellreceived. Both soldiers and officers had long-h held ideas about what military weapons should look like. The difference from the Thompson was big. Soldiers expected polished wood and machine steel. Instead, they got stamped metal and spot welds that looked rough.

Staff Sergeant William Morrison at Fort Benning’s Infantry School said, “It feels cheap in your hands. Looks like something you’d find in a garage, not an armory. The boys are calling it the grease gun and not in a good w.” The nickname stuck, showing both the weapon’s simple look and the doubt it created among troops.

The Army also had concerns about replacing an iconic weapon with what seemed to be a mass-roduced substitute. Colonel James Harrison, chief of small arms training at the infantry school, said, “The M3 may function adequately, but it fails to inspire confidence in our soldiers. Military effectiveness depends not merely on mechanical function, but on the warrior’s faith in his weapons.

” This stamped metal substitute undermines that crucial psychological element. The complaints went beyond looks and included performance. The M3’s 450 rounds per minute was criticized as slow compared to the Thompson’s 700 Plus, even though Hyde had done it on purpose to improve control and save ammunition. The wire stock was called flimsy even though it was lighter and more compact than wood.

The simple safety was called crude, even though it was more reliable and easier to use than complex systems. Training officers said that soldiers needed extra instruction to trust the M3’s unusual design. Range reports showed that troops shot more accurately with the M3 because it was easier to control, but many thought it was due to other things rather than the weapon itself.

The psychological barrier created by the M3’s appearance was harder to overcome than the technical challenges Hyde had solved. Some senior officers asked that Thompson production be restarted to maintain American military standards. They talked about soldier morale, weapon prestige, and the intangible things that made a military effective beyond just how well the weapon worked.

The ugly gun that had solved America’s production problem was being rejected by the very people it was meant to serve, creating a crisis of confidence. The M3 was proven right not in training camps, but in combat, where how it looked didn’t matter as much as how well it worked. By mid 1944, American forces were finding that Hyde’s ugly gun had qualities that no amount of traditional craftsmanship could replace.

Tank crews were the first to appreciate the M3 because they knew how important space was inside a tank. The Thompson’s length made moving inside Sherman and Stewart tanks difficult. The M3 shorter length made it easier to use in tight spaces. Staff Sergeant Robert Hayes, who commanded an M4 Sherman during the Italian campaign, said, “You try swinging a Thompson around inside a tank turret when German soldiers get close.

The grease gun fits where the Tommy won’t go. Had to engage German soldiers at point blank range yesterday. The M3 let me get my weapon up and firing while my loader was still wrestling his Thompson into position. The weight was also important. At 8.2 lb, compared to the Thompson’s 10 Plus, the M3 reduced fatigue during long operations.

During combat jumps, paratroopers, weighed down by all their gear, quickly realized that even a small weight difference in weapons could add up to a big advantage for the unit as a whole. An official report from the 82nd Airborne during Operation Market Garden noted that squads using the M3 submachine gun could carry extra ammo and medical supplies compared to units with the Thompson.

But really, it was in the Pacific theater where the M3 showed what it could do. The jungle environment was brutal. The high humidity and constant rain caused problems for standard weapons. The Thompson, for instance, needed to be cleaned daily to avoid rust and jams because of its exposed parts. But that was hard to do when soldiers were constantly on the move and could run into the enemy at any time.

Marine Corporal Anthony Richie wrote in his journal from Buganville about how reliable weapons were crucial in the jungle. On day two, his Thompson started jamming constantly due to the humidity. He picked up an M3 from a wounded soldier and that thing just kept firing no matter what. For 3 weeks, he fired 800 rounds, never cleaned it, and it never jammed.

Even when he dropped it in a stream during a night patrol, officers back in Aberdine had thought the M3’s enclosed design looked crude, but it turned out to be a gamecher in places where standard designs just couldn’t hold up. The M3’s bolt and springs were protected from the moisture, dirt, and junk that messed up Thompson mechanisms, even when they were well-maintained.

Field reports from the Pacific showed that the M3 had a reliability rate of over 95% while the Thompson’s rate dropped below 70% during long operations in the jungle. Back in Europe during the winter of 1944 to 45, the Battle of the Bulge put American weapons to the test in freezing conditions.

The cold showed the differences between standard and newer designs. The Thompson’s mechanism would freeze solid, making it useless when German forces launched surprise attacks. Private First Class Michael Sullivan of the Second Infantry Division rode home on December 23rd, describing the combat in winter. The temperature dropped way below zero.

The Germans attacked before sunrise. A friend’s Thompson froze up completely and he couldn’t even pull back the bolt. But Sullivan’s M3 kept working without issues. He said that the ugly gun saved our whole squad that morning. The M3’s simple design and fewer moving parts were better in extreme weather. The Thompson’s complex mechanism needed precise conditions, which the cold messed up, but the M3’s tough build and simple operation kept it running.

The bolt, which some people thought was too heavy, actually worked better in sub-zero temperatures because it kept moving when lighter mechanisms failed. German intelligence reports from the Ardan offensive specifically marked out American units with M3s as priority targets. They knew how well the weapons worked in close quarters winter fighting.

One captured report said that the American grease gun M3 was very dangerous in bunker clearing operations. It was simple, reliable, and worked even when other weapons didn’t due to the cold. American soldiers opinions about the M3 changed over time. At first, they were skeptical, but they began to respect it as they realized it worked really well.

The nickname grease gun went from being a joke to a term of endearment as soldiers learned to trust the design. Technical Sergeant David Chun, who fought in Italy and France, talked about how his unit’s view of the M3 changed. He said that they initially called it the grease gun as a joke because it looked like something from a garage.

Still, after 6 months of combat, that garage tool brought more of them home alive than any fancy weapon. He learned that function is more important than looks. Just as the M3 was being recognized for being effective, the program ran into problems. In early 1945, quality control issues started to surface as production ramped up. Some M3s had weak springs that caused feeding problems, and others had bolts that broke during long periods of firing.

Critics who had disliked the program from the start used these problems to justify their complaints based on how the gun looked and their own biases. The problems threatened to undo all the good that the M3 had done through its design. Orders came to stop making M3S and go back to producing Thompsons.

Despite the evidence from combat that the M3 was superior, the newer weapon faced being cancelled because of old ways of thinking. The news that reached Hyde’s office in Dayton in February 1945 was strangely ironic. The last Thompson had rolled off the assembly line at Savage Arms. Not because it was outdated, but because it was too expensive to make.

After producing 1 and a half million Thompsons, the beautiful gun became too costly to keep making. The Thompsons and created a gap that only the M3 could fill. But the quality issues threatened to kill the M3 program right when it was needed most. Hyde worked with Frederick Samson to find and fix the production problems.

They discovered that quickly expanding production facilities had messed up the steel and spring specifications that made the weapon reliable. They used the same simple approach to solve the problems that had guided the creation of the M3. Better steel and revised spring tension fixed the bolt breakage and feeding issues. The improved M3A1, introduced in December 1944, addressed every complaint while keeping the cost and production advantages that allowed mass production.

The most obvious change was replacing the cocking handle with a simple hole in the bolt, which got rid of the part most likely to break. A stronger rear sight improved accuracy while still being cheap to make using car manufacturing techniques. Most importantly, stricter quality control eliminated the problems that had caused reliability issues.

By the end of the war, the proof of the M3’s superiority was clear. Total M3 production reached over 600,000 units, saving over $150 million compared to producing the same number of Thompsons. The reliability rate in final testing reached almost 100%, even better than Hyde had hoped. The weapon that had been called crude had become more reliable than any other submachine gun in American history.

But the M3’s rail test came during the Korean War where freezing conditions caused problems for most weapons. The conflict was a final argument in the debate of function versus looks. The weather removed any consideration for how a weapon looked and showed what was most important, how well it worked. Private Bob Shine of the Second Infantry Division saw that the M3 worked better in winter during the retreat from Seoul in January 1951.

His unit faced Chinese forces in freezing conditions, which made weapon reliability essential. Shin recalled that he hated the gun when they gave it to him at Fort Lewis because it looked like junk compared to the fancy Thompsons in the movies. But when they attacked Chinese positions, his M3 fired every round.

His buddy with a Thompson jammed after 10 shots. He said that the ugly gun brought me home. Chinese Army reports from the spring offensive specifically targeted American soldiers with M3s, recognizing how effective the weapon was in close quarters fighting. Intelligence assessments noted that the weapon was reliable and that units with M3s were threats during infantry assaults.

The opinion of the American military changed as the weapon proved its capabilities. What started as a source of jokes became a point of respect as officers who had first criticized its look came to appreciate its usefulness. By 1953, even traditional military leaders admitted that Hyde’s ugly gun was more reliable than the Thompson it replaced.

The idea that Hyde had shown became a principle that influenced American military purchases for years. Function wins over form. Good wins over perfect. Usefulness determines weapon selection, not looks. These ideas, which were revolutionary when Hyde first proposed them, became the standard that guided everything from small arms to major weapon systems.

George Hyde died in 1963 with his design still in use by the American military, outlasting the critics and the biases that had fought against it at first. The M3 served through Korea, Vietnam, and beyond, building a record that showed the value of Hyde’s design. The M3’s legacy extended beyond its service, showing a shift in American thinking.

The grease gun proved that were more concerned with how a product looked. For the soldiers who carried M3s through three wars, the weapon’s appearance didn’t matter as much as its dependability. They learned that in military equipment, beauty isn’t about a polished surface or fancy design. It’s about working consistently when lives are on the line.

The grease gun’s simple design showed American ingenuity at its best. The ability to remove what isn’t needed while keeping what’s most important. In the end, George Hyde’s ugly gun taught America that the best solution is the one that works every time when it matters. The principle that he established became a base of American military thinking.

Usefulness, not looks, determines value. The M3 proved that sometimes the most revolutionary thing is making something simple enough to work perfectly when it’s needed.

News

Why the Viet Cong Feared the SAS More Than Any American Unit

Fuaktui Province, South Vietnam, March 17th, 1966. The Vietkong sentry never heard them coming. Nuan Vanam had survived 2…

They Mocked His “Backwards” Loading Method — Until His Sherman Destroyed 4 Panzers in 6 Minutes D

At 11:23 a.m. on September 19th, 1944, Private First Class Walter Kowalsski crouched inside his M4 Sherman tank near…

The Most Insane Helicopter Pilot of Vietnam – Ace Cozzalio D

Oh, good girl. You want to hear the story about the deadliest IHOP employee to have ever existed? Yeah….

Why American Soldiers Started Killing Their Own Officers in Vietnam D

Today’s video is brought to you by the good people over at AG1. I told myself I wasn’t doing…

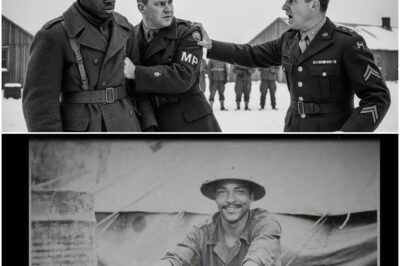

How Canadians Stood Up for Black GIs After U.S. MPs Crossed the Line D

July 1944, Aldershot, England. The summer air hung thick and warm inside the Red Lion Pub. Canadian soldiers sat…

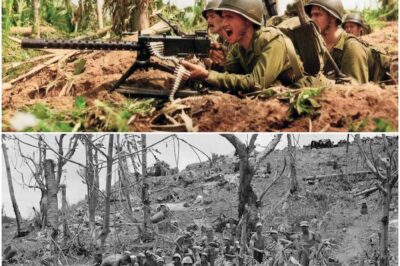

Why U.S. Marines Waited for Japan’s “Decisive” Charge — And Annihilated 2,500 Troops D

July 25th, 1944. Western Guam, Our Peninsula. A narrow strip of land barely half a mile wide, shielding the…

End of content

No more pages to load