Imagine being trapped on a Pacific island, surrounded by thousands of Japanese soldiers, determined to destroy your position. Your weapons are malfunctioning, your ammunition is running low, and command says there are no reinforcements available. It was in this impossible situation that a marine mechanic considered eccentric by his comrades decided to do the unthinkable.

Create a completely new weapon using only scrap metal from the war. What he built that night would change the course of one of the bloodiest battles of World War II. This is the true story of innovation under enemy fire that saved hundreds of American lives. In August 1942, the United States launched its first major offensive against the Japanese Empire on the island of Guadal Canal in the Solomon Islands.

The First Marine Division landed on the beaches under the command of Major General Alexander Vandergrift, beginning what would be a six-month campaign that would test the limits of human endurance. The Marines quickly captured the unfinished airfield the Japanese were building, renaming it Henderson Field. But holding that position would be far more difficult than capturing it.

The Imperial Japanese Army had no intention of allowing the Americans to hold that vital strategic point. Among the thousands of Marines fighting in those brutal conditions was Sergeant John Basilone, who would become a living legend before the end of that campaign. Born in Buffalo, New York in 1916, Basselone had served in the army before enlisting in the Marines in 1940.

He was known for his exceptional skill with machine guns, but also for his ingenuity in solving mechanical problems. The conditions on Guadal Canal were absolutely terrible. The dense jungle, the suffocating heat exceeding 40°, the constant humidity that caused everything to rot quickly, and tropical diseases made each day a battle for survival.

Malaria, dissentry, and tropical infections weakened the men almost as much as direct combat. Supplies arrived sporadically. Transport ships risked air and submarine attacks to bring ammunition, food, and medical equipment. Often, the Marines had to ration everything from bullets to drinking water.

Equipment rusted quickly in the tropical humidity, and keeping weapons operational was a constant challenge. Japanese forces controlled the sea at night, bombarding American positions with naval artillery. The Marines nicknamed this night terror pistol Pete and Louis the liar. The naval guns that kept them awake and terrified every night.

During the day, Japanese planes based at Rabul repeatedly attacked Henderson Field. But worst of all were the Japanese ground attacks. The Japanese high command constantly sent reinforcements determined to drive out the Americans. Japanese tactics were aggressive and often suicidal. They attacked in waves, shouting and firing, testing American defenses until they found a weak point.

Japanese officers trained in the Bushido tradition preferred death to the dishonor of surrender. This made every engagement extremely dangerous as wounded soldiers often attempted to attack with grenades or bayonets, even when clearly defeated. The Marines quickly learned never to let their guard down.

The American perimeter around Henderson Field was constantly tested. Japanese patrols probed the defenses, searching for weak points. Japanese snipers known as Tokyo Rose to the Marines hid in the trees and caught unsuspecting targets. The tension was constant and sleep was a rare luxury. In this hellish scenario, ordinary men were forced to do extraordinary things just to survive another day.

The night of October 24th to 25th, 1942 would be recorded in Marine history as one of the most heroic defenses ever seen. American intelligence had detected massive movements of Japanese troops preparing for a full-scale attack against Henderson Field. General Harukichi Hyakutake, commander of the Japanese 17th Army, had meticulously planned what would be the final blow against the Americans.

He mustered approximately 20,000 soldiers to crush the defenders once and for all. Japanese confidence was so high that Tokyo had already announced imminent victory. The Marines prepared as best they could. Machine gun positions were reinforced. Firing ranges were cleared and ammunition was distributed, but everyone knew they would be dramatically outnumbered.

Many positions would be defended by only a handful of men against hundreds of attackers. John Baselone commanded a machine gun section positioned in a critical area of the perimeter known as Bloody Ridge. His position blocked one of the main routes the Japanese would need to reach the airfield. If that line were breached, the entire defense could collapse.

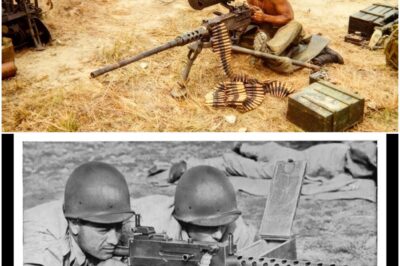

With Baselon were about 15 marines operating Browning heavy machine guns of 30 caliber. These weapons were absolutely vital for defense, capable of firing 500 rounds per minute and cutting through massed infantry formations, but they were also prone to overheating and jamming, especially when fired continuously. As darkness fell over the jungle, a palpable tension gripped the American positions.

The men repeatedly checked their weapons, adjusted their helmets, and smoked their last cigarettes. Many wrote hurried letters home, unsure if they would live to see the dawn. Around 9:30 p.m., the bombardment began. Japanese artillery hammered the American positions with an intensity that many veterans had never experienced. The earth trembled, trees were shattered, and the air became thick with the smell of gunpowder and churned up earth.

Then through the smoke and darkness came the screams. Thousands of Japanese soldiers emerged from the jungle in human waves, attacking American positions with desperate ferocity. They shouted, “Banzai and Marine, you die today.” As they raced across no man’s land, Basselone’s machine guns opened fire, creating a wall of lead that felled the attackers in ranks.

But for every Japanese soldier who fell, two others seemed to take his place. The pressure was unbearable, and the noise was deafening. Machine guns thundering, grenades exploding, men screaming in agony. During the first hours of battle, everything went according to plan. The machine guns kept the Japanese at bay despite the terrible cost in human lives on both sides.

But then the problems began that would turn that night into a legend. One by one, Basilone’s machine guns began to malfunction. The intense heat from the continuous fire caused the barrels to glow red. Some jammed with warped cartridges. Others simply stopped working due to the accumulation of carbon and dirt. The situation was quickly becoming desperate, and it was precisely in this moment of maximum crisis that true genius under pressure would be revealed.

As night wore on, the situation at Balon’s position became increasingly critical. Waves of Japanese infantry kept coming, seemingly endless. Bodies piled up before the American positions, but the attackers simply jumped over their fallen comrades and continued advancing. The biggest problem wasn’t the defender’s lack of courage or determination, but rather the mechanical failure of their weapons.

The Browning M1917 machine guns, while excellent weapons under normal conditions, were never designed to fire continuously for hours on end without stopping. The heat generated by friction was so intense that the barrels literally glowed in the darkness. Basilone quickly realized he needed to act. He rushed from one machine gun position to another, assessing the damage.

Some guns had barrels so overheated they were slightly warped, affecting accuracy. Others were completely jammed with cartridges that had literally melted in the chambers. A third had broken a vital component of the recoil mechanism. Standard procedure was to replace the barrels when they became too hot.

But this required spare barrels and time, two resources that were critically scarce that night. The spare barrels had been damaged by Japanese bombing, and there was no time to wait for them to cool down properly. Other marines in the position began to panic. Without their machine guns operating at full capacity, the Japanese would certainly break through the lines.

And once they broke the perimeter, it would be nearly impossible to stop them before they reached Henderson Field. Everyone knew what that would mean. Basilone, however, maintained absolute calm. While Japanese tracer bullets sliced through the air around him, and grenades exploded close enough to throw dirt in his face, he began to examine the broken weapons with the cool mind of a seasoned mechanic.

He had grown up working with machinery. Before enlisting, he had worked as a caddy at a golf course, but he also helped his father, a tailor who kept his own sewing machines running. Basilone understood metal. He understood heat. He understood mechanics in an intuitive way that few possessed. Looking at the broken and damaged weapons around him, his brain began to work on a solution.

He couldn’t simply wait for the weapons to cool down, and he didn’t have any suitable replacement parts. But maybe, just maybe, he could improvise something that would work. The idea that came to him was radical and had never been attempted before on the battlefield. He would need to combine parts from multiple damaged weapons, create improvised adaptations, and essentially build functional machine guns from scrap metal.

and he would have to do this in the midst of one of the most intense battles of the war. But Baselon had no choice. Either he found a solution or the position would fall. It was that simple. He shouted orders for his men to keep firing rifles and throwing grenades while he worked. Every second counted, and the Japanese kept pressing.

Under the glare of the explosions and the intermittent light of the illumination rockets, Baselone began to work with frenetic speed. His hands burned by the superheated pipes, but without hesitation began to disassemble and reassemble weapon components. What he was about to create would change the course of that bloody battle.

With bullets whizzing overhead and explosions shaking the ground beneath his feet, John Basselone embarked on what would be considered one of the most extraordinary feats of mechanical improvisation in military history. He had several broken machine guns, a deep understanding of how they worked, and a desperate need to get them working again.

The first problem was the overheating of the barrels. Bascelona knew he couldn’t simply replace the barrels without letting them cool down properly, as this could cause even more deformation. But he noticed something. Some of the machine guns had less damaged barrels than others, and some had other components working perfectly while the barrels were ruined.

He began disassembling the weapons with impressive speed. Each Browning machine gun consisted of dozens of precisely fitted parts. the barrel, the recoil system, the feed mechanism, the safety, the firing pin, the springs. Basilone knew each of these parts intimately. His hands worked in the dark, guided more by touch and muscle memory than by sight.

He removed screws, slid entire assemblies out, and began to create combinations of components that were never designed to work together, but which theoretically could function. One of the Marines, Private First Class Robert Powell, watched in astonishment while holding an armored flashlight that gave off only the bare minimum of light.

Powell would later report that Basilone seemed to be in a trance, totally focused on his work, despite the absolute chaos around him. Basilone took the recoil mechanism from one weapon, the bolt assembly from another, and the feeding system from a third. He was essentially building hybrid machine guns, taking the best functional parts from multiple damage weapons and creating new functional systems.

But there was a critical problem that demanded an even more creative solution. The pipes that were still functioning were getting dangerously hot, and without water or suitable oil to cool them, Basilone needed to find another solution. It was then that he had an idea that would seem absurd in any other context.

He ordered his men to urinate in their helmets and bring them to him. In the darkness of the Guadal Canal jungle, with the Japanese only meters away, Marines rushed to Basilon’s position with helmets filled with urine to use as makeshift cooling fluid for their overheated machine guns. The technique worked. The urine, while not ideal, provided enough cooling to keep the barrels at operating temperature for a few more minutes.

Basilone poured the liquid over the smoking barrels, which hissed and created clouds of acrid vapor, but cooled down enough to continue firing. Meanwhile, he continued his reconstruction work. One of the machine guns had a problem with the feeding system that caused the ammunition belt to jam after only a few shots. Baselone realized that the problem was a spring that had lost tension due to heat.

He removed the spring from a completely destroyed weapon, cut it to the right size with pliers, and installed it in place of the defective spring. In another weapon, the locking system was working intermittently. Baselone disassembled the assembly, cleaned the carbon buildup with a knife, and applied rifle oil to the friction points.

The weapon then began firing smoothly again. All the while, explosions kept shaking their position, and he could hear his fellow Marines shouting orders and warnings about new Japanese attacks forming in the darkness. After approximately 45 minutes of frantic work under impossible conditions, Basilone had achieved the impossible.

From five completely broken or barely functioning machine guns, he had created three fully operational weapons and a fourth that functioned intermittently but was still useful. He personally repositioned each machine gun, taking advantage of the terrain and fields of fire as best as possible. Basilone intuitively understood how to position automatic weapons to create crossfire.

A technique where bullets from multiple weapons cross over a kill zone, making it virtually impossible for the enemy to cross without suffering massive losses. When the modified machine guns opened fire again, the effect was immediate and dramatic. The Japanese, who had begun to press more aggressively upon realizing that American fire was diminishing, suddenly found themselves once more under a deluge of devastating machine gun fire.

But Basilone didn’t stop there. He realized that his positions were beginning to run dangerously low on ammunition. The cartridge belts feeding the machine guns were being consumed at an alarming rate. The nearest ammunition supplies were about 50 m away across open terrain that was being swept by Japanese fire.

Without hesitation, Baselon grabbed his helmet, now empty after being used to cool the weapons, and began running through the kill zone to retrieve more ammunition. Japanese bullets ricocheted off the ground around him as he zigzagged, using every dip in the terrain and every fallen tree as temporary cover. He reached the ammunition depot and began carrying straps of cartridges over his shoulders.

Each strap weighed approximately 5 kg, and he carried as much as he could, probably more than 40 kg of ammunition. Then he made the run back again under heavy fire. Sergeant Manila John Basilone would make this dangerous run multiple times during the night, always refusing to allow other men to take the risk.

Each time he returned with ammunition, his marines would shout encouragement and quickly load their machine guns to continue firing. At one point during the night, a group of Japanese soldiers managed to infiltrate dangerously close to Basilone’s position. They were only a few meters away when they were discovered.

Basilone immediately grabbed one of the machine guns, which was still mounted on its tripod, lifted the entire weapon weighing almost 20 kg, and fired from the hip as if it were a rifle, sweeping away the attackers. This maneuver, though dramatized in later films, actually happened and was witnessed by multiple Marines. The Browning machine gun weighed approximately 18 kg without ammunition, and firing from the hip required exceptional strength and control as the recoil was brutal.

But Baselone succeeded, saving his position from being overrun. As night wore on into the early hours of the morning, the Japanese attacks began to lessen in intensity. The losses they had suffered were absolutely devastating. Hundreds, possibly thousands of Japanese soldiers laid dead before the American positions. The cost of the attack had been far greater than the Japanese high command had anticipated.

As the first light of dawn began to illuminate the horizon, revealing the full extent of the carnage, it became clear that the Marines had held their ground. Henderson Field was saved, and with it the entire Guadal Canal campaign. When the sun rose over Guadal Canal on the morning of October 25th, 1942, it revealed a scene of almost incomprehensible destruction.

The area in front of Basilone’s position was literally covered with the bodies of Japanese soldiers. Later, estimates would suggest that more than a thousand enemy soldiers had been killed in that section of the perimeter alone. Baselone’s machine guns were still smoking, their barrels warped by the intense heat, but still operational.

Empty ammunition belts lay scattered everywhere along with hundreds of spent cartridges. The ground was marked by grenade craters and stained with blood. Basilone was covered in soot, sweat, and blood, most of it not his own. His hands were severely burned from handling overheated pipes during the night, but he had refused to stop for medical treatment.

His eyes were red from lack of sleep and exposure to gunpowder, but he remained at his post, ensuring his machine guns were ready should the Japanese attack again. Officers who inspected Basilone’s position that morning were absolutely astonished by what they saw. Major General Alexander Vandergrift personally visited the area and spoke with Baselon and his men.

What they reported seemed almost impossible to believe. A single sergeant had kept a critical section of defense, functioning through sheer determination, mechanical skill, and extraordinary courage. The other marines in Basilone’s position had also fought with exceptional bravery, but they all credited their sergeant with saving them.

Without his work keeping the machine guns running, the position would certainly have been overrun. And if that position had fallen, it could have created a breach in the perimeter that the Japanese could have exploited. The Japanese attack of October 2425 had been the most significant effort to retake Henderson Field, and its failure marked a crucial turning point in the Guadal Canal campaign.

The Imperial Japanese Army had suffered losses that it could not easily replace, and the morale of the Japanese troops began to deteriorate significantly after this defeat. In the following days, American patrols found evidence of just how devastating the machine gunfire had been. Japanese soldiers had died in dense formations, some still holding their weapons, others clearly having been hit while trying to carry wounded comrades.

The diaries found on the bodies revealed the terror that the American machine guns had inspired. A captured Japanese officer would later recount that his troops had been repeatedly ordered to attack that specific position and [clears throat] each time were decimated by diabolical American guns that never stopped firing. He had no idea that those guns had malfunctioned multiple times and been revived by a single ingenious mechanic.

War correspondents began hearing stories about the sergeant who had singlehandedly held a critical position. News spread across American lines and Basilone quickly became a legendary figure among the Marines. Other mechanics and armorers began studying his improvised repair techniques. But for Basselon, it wasn’t about glory or recognition.

When asked about his actions that night, he simply said he was doing his job and looking after his men. This genuine humility only increased the respect other Marines had for him. The battle that would become known as the Battle of Henderson Field or the Battle for the Bloody Crest was over, but its impact would reverberate throughout the rest of the war.

In the weeks following the battle, Marine Command conducted detailed interviews with all participants in the defense of Henderson Field. Witness accounts of John Baselone’s actions were remarkably consistent and extraordinary. Multiple Marines, including officers, confirmed not only his bravery under fire, but also his exceptional technical skill in keeping weapons functioning.

Lieutenant Colonel Lewis Puller, commander of the first battalion of the seventh marine regiment and himself one of the most decorated officers in the core’s history, personally recommended Baselone for the highest American military decoration, the Medal of Honor. The official citation would describe how Baselone materially contributed to the defeat and virtually the annihilation of a Japanese regiment.

It would note that he repaired weapons, loaded ammunition through intense fire, and personally killed an estimated 38 Japanese soldiers that night. But what the official citation failed to fully capture was the most extraordinary aspect of their actions, the sheer ingenuity of rebuilding functional machine guns from broken weapons in the midst of battle.

This kind of improvised thinking under extreme pressure represented precisely the type of innovation that would win the war in the Pacific. In May 1943, John Basilone was recalled to the United States to receive the Medal of Honor from General Alexander Vandergrift who had been promoted to commandant of the Marine Corps.

The ceremony took place at the Australian Memorial in Canra and Basilone became the first enlisted marine to receive the Medal of Honor in World War II. Baselone’s story captured the imagination of the American public at a time when the country desperately needed heroes. He was taken on a war bond tour across the United States, appearing at rallies where crowds gathered to see him and hear his stories.

He raised millions of dollars in war bonds. During this tour, Baselone visited weapons factories and met the workers who manufactured Browning machine guns. He shared his experiences with them, including the problems he had encountered with overheating and jamming. His observations led to some minor design modifications that improved the reliability of the weapons in intense combat conditions.

He also visited marine training camps where he demonstrated proper machine gun handling techniques and shared lessons learned at Guadal Canal. Young Marines hung on his every word, eager to learn from someone who had proven his worth in real combat. But Basilone wasn’t comfortable with all the attention.

He was fundamentally a man of action, not words. The celebrity life and war bond rallies made him uneasy. He felt his place was with his fellow Marines in the Pacific, not parading before crowds in the United States. He repeatedly requested a return to combat. The Marine Corps initially refused. Baselone was too valuable as a symbol and public relations tool.

They offered him an officer commission and comfortable training positions in the United States. He refused everything. Finally, in December 1943, after months of persistent requests, the Marine Corps agreed to send him back into combat. Baselone was assigned to the 27th Marine Regiment, Fifth Marine Division as a weapons instructor, but everyone knew it was only a matter of time before he was back on the front lines.

In early 1944, John Basilone was back in the Pacific. this time preparing for one of the most ambitious amphibious invasions of the war, the capture of Ewima. The small volcanic island just a thousand kilometers from Tokyo was absolutely vital to American plans to bomb mainland Japan and eventually invade it.

Basilone trained Marines in Charlie Company of the First Battalion, 27th Regiment. He shared everything he had learned at Guadal Canal. How to keep weapons functioning in adverse conditions, how to position machine guns for maximum effect, how to improvise when equipment failed. The young Marines under his command quickly realized they were learning from someone who truly knew what he was talking about.

Baselone didn’t teach textbook theory. He taught survival techniques earned with blood in real combat. His lessons were practical, direct, and focused on what really mattered in battle. During training, Basilone personally demonstrated each technique. He disassembled and reassembled machine guns blindfolded, explaining each component by touch.

He taught the Marines to identify mechanical problems by sound and feel. He showed them how to perform field repairs with minimal tools. But he also taught something more important than technical skills. He taught the mindset of a combat marine. Calm under pressure, clear thinking when chaos reigns, caring for your comrades above all else.

These lessons were perhaps more valuable than any technical instruction. In July 1944, while still training troops, Basilone met Lena Mayriggi, a sergeant in the Women’s Marine Corps who was stationed at Camp Pendleton. Their romance was swift and intense, two professional Marines who understood the demands and purpose of military service.

They married in July 1944. Lena tried to convince Jon to accept one of the permanent instructor positions the core continued to offer. She knew he had done more than his part, had proven his courage beyond any doubt. If I don’t go with them, some of them won’t come back, he explained to Lena. It was that simple for him.

He had trained these marines, and he felt a personal responsibility for each one of them. Lena, being a Marine herself, understood, even though it broke her heart, in December 1944, the 27th Marine Regiment embarked for Hawaii for final training before the invasion of Ewima. American intelligence knew it would be an incredibly difficult battle.

The Japanese had transformed the entire island into a fortress with miles of tunnels, reinforced concrete bunkers, and carefully camouflaged artillery positions. General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, the Japanese commander of Ewoima, was one of the most capable officers in the Imperial Army. He had abandoned the traditional banzai attack tactics, which had proven ineffective against American firepower.

Instead, he planned a defense in depth that would bleed the Americans dry from every inch of the island. Basilone and the other marines studied maps and aerial photographs of Ewima. The island seemed desolate. A few square kilometers of volcanic ash and rock dominated by Mount Suribachi to the south.

But everyone knew that beneath that barren surface awaited thousands of Japanese soldiers determined to sell their lives for as much as possible. On February 19th, 1945, the Battle of Ewima began. At 9 in the morning, after a massive naval bombardment, the first waves of Marines reached the beaches. John Basselone was among them, landing on Green Beach with Charlie Company.

The beach was composed of black and gray volcanic sand with the consistency of coarse gravel, making every step a struggle. Vehicles sank up to their axles, and men struggled to climb the sandy terraces that led inland. It was exactly the kind of terrain where heavy equipment would easily get stuck. Initially, Japanese resistance seemed surprisingly light.

The Marines advanced from the beach without the massive casualties that many had predicted. But this was part of Kuribayashi’s plan to let the Americans land, then hit them with everything once they were grouped on the beach and in the surrounding areas. When the attack came, it was devastating. Japanese artillery and mortars pre-selected every meter of the landing zone began to rain down on the Marines.

Machine guns hidden in camouflage bunkers opened fire. Suddenly, the beach was transformed into a hell of steel and fire. Barcelona immediately identified one of the biggest problems. Tanks and armored vehicles were stuck in the soft volcanic sand, becoming stationary targets for Japanese artillery. Without these vehicles advancing, the infantry was exposed and vulnerable.

He gathered a group of Marines and began working to free the stuck vehicles. Under intense fire, they dug around the tank tracks, placed metal plates under the wheels, and did everything they could to give traction to the trapped vehicles. It was dangerous and exhausting work under the worst possible conditions.

While working, Baselone continued to direct and encourage his men. He identified Japanese gun positions and coordinated suppressive fire. When a particularly troublesome Japanese bunker continued to mount the Marines attacks, Basilone personally led an assault against it, using demolition explosives to destroy the position.

Throughout this time, he was constantly exposed to enemy fire. At other times, he would have sought cover, waited for support, coordinated with neighboring units. But the situation was desperate, and Bascelone knew that every minute lost cost marine lives. Around noon, he had helped refloat several vehicles and neutralized multiple enemy positions.

The Marines were beginning to advance inland, albeit at a terrible cost in casualties. Basilone remained on the front line doing exactly what he had told Lena he would do, looking after his men. It was at that moment while coordinating his unit’s movement through a minefield that a Japanese mortar explosion struck near Basilone.

The machine gun that made him legendary at Guadal Canal could not protect him from the random and brutal chance of war. John Baselone was killed instantly. He was 27 years old. Around him, the Marines he had trained and led continued the fight, applying the lessons he had taught them. They would climb Mount Suribachi, raise the American flag on its summit, and eventually take the entire island after 36 days of some of the war’s most brutal fighting.

Baselone was initially buried in the fifth marine division cemetery on Ewima before being reinterred in Arlington National Cemetery years later. The death of John Baselone on Ewima shocked the United States. Here was a man who had already done the impossible on Guadal Canal, who had been decorated with the nation’s highest military honor and who could have remained safely in the United States.

Instead, he chose to return to combat because he felt it was his duty to protect the younger marines under his command. For his actions on Ewima, Basilone was postumously awarded the Navy Cross, the second highest American military decoration. This made him one of the few Marines to receive both the Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross.

A testament to exceptional valor demonstrated twice in completely different circumstances. But John Basilone’s true legacy goes beyond his decorations. The techniques he developed on Guadal Canal for keeping weapons functioning under extreme conditions were incorporated into marine training manuals.

Generations of armorers studied his improvised field repair methods. The story of how he rebuilt machine guns from damaged parts, cooled overheated barrels with whatever liquid was available, and maintained a critical operational position through sheer ingenuity became a case study in innovation under pressure. Military schools around the world still use Basilone’s example when teaching about adaptive thinking in combat.

Most importantly, Basilone exemplified something fundamental about the human spirit, the capacity to do the extraordinary when absolutely necessary. He wasn’t a genius with special engineering training. He was simply a competent mechanic with a deep knowledge of his weapons who refused to accept defeat when all seemed lost.

This mentality, this refusal to give up, this determination to find a solution, no matter how impossible the situation seems, is perhaps the most valuable lesson from Basilone’s story. It wasn’t just about fixing weapons. It was about remaining calm when others panicked, thinking clearly when chaos reigned, and doing what needed to be done even when it seemed impossible.

The nickname mad mechanic, though not formally documented in official military records, perfectly captures how his fellow Marines viewed his actions that night on Guadal Canal. What he did seemed like madness, working on broken weapons while bullets whizzed past his head, repeatedly exposing himself to enemy fire to retrieve ammunition, improvising solutions that had never been tried before.

But it was exactly the kind of madness that wins wars. The willingness to do the unthinkable when the stakes can’t be higher. Today, the story of John Basselone is taught to all Marines during basic training. There are statues of him in his hometown of Raritan, New Jersey. A bridge on Interstate 95 is named after him.

He has been portrayed in films and in the HBO series The Pacific. But perhaps the most significant tribute is simply this. 79 years after that night on Guadal Canal, when a mechanic did the impossible and saved dozens of lives through sheer ingenuity and courage, Marines are still learning to think creatively under pressure.

To never give up, no matter how difficult the situation, and to always look out for their comrades. This is the true legacy of John Basilone. Not just the weapons he repaired or the enemies he defeated, but the example of excellence he set that continues to inspire generations of warriors. is

News

Japanese Troops Shocked by 12 Gauge Shotguns! D

November 2nd, 1943. Buganville Island, Solomon Islands. The jungle air hung thick as wet cloth against Private Tanaka’s face…

Japanese Soldiers Were Terrified When They Found U.S. Marines Used Machine Guns as Sniper Rifles D

On the morning of June 22nd, 1944, at 6:47 a.m., Corporal Jack McKver crouched behind his Browning M2 heavy…

The Native Warrior Most Feared by the Germans in World War II D

Have you ever wondered what could make an entire German regiment refuse to advance even under direct orders from…

How One Navajo Soldier’s ‘CRAZY’ War Cry Made 52 Germans Think They Were Surrounded D

October 15th, 1944. The Voj mountains of eastern France stood wrapped in morning fog so thick that Lieutenant James…

The “Broken Glass Method” That Let U.S. Snipers Spot 87 Hidden Japanese Soldiers in One Afternoon D

On the afternoon of September 14th, 1944, the tropical sun hung mercilessly over the dense jungle canopy of Paleu…

German Pilots Couldn’t Believe the B-17’s 16 Guns — Until the “Flying Fortress” Collapsed D

the bomber that tried to become a fighter and failed brilliantly. At 11:47 a.m. on May 29th, 1943, [music]…

End of content

No more pages to load