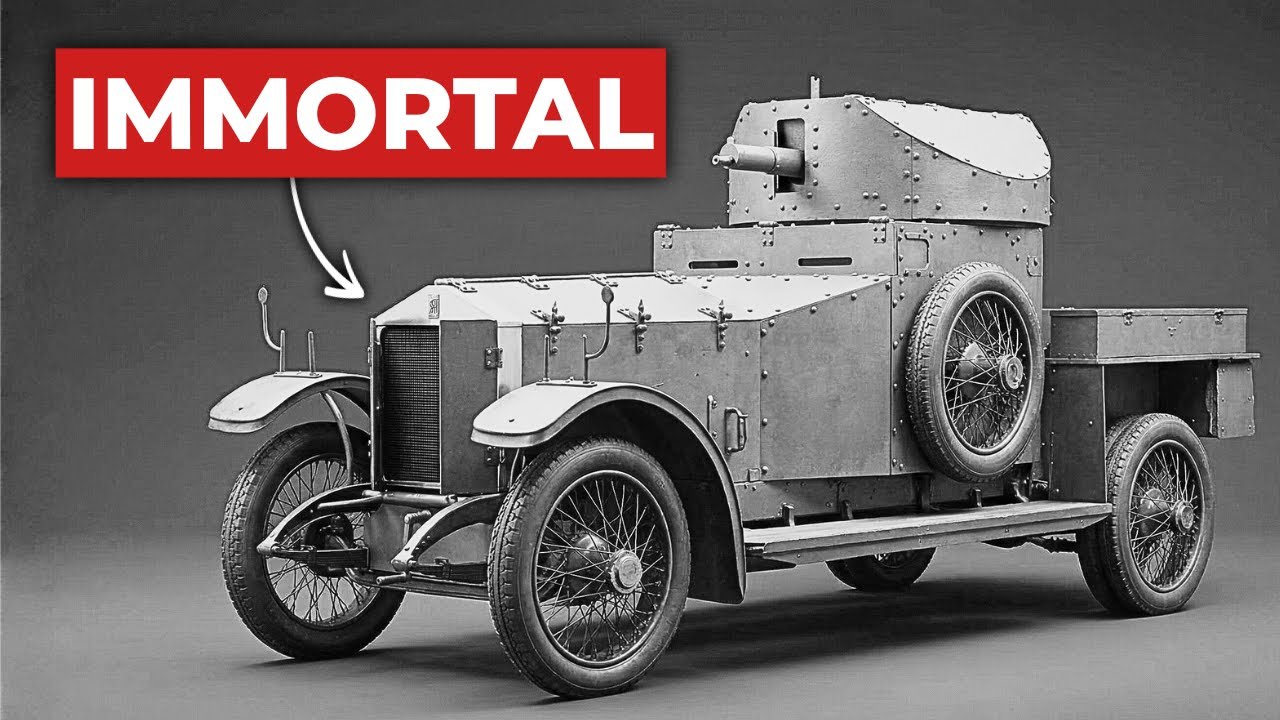

September 1914, a shipyard in Dunkirk, Northern France. Commander Charles Rumley Samson of the Royal Naval Air Service watched his men bolt 6 millm boiler plate onto the body of a Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost touring car. The steel had been scavenged from a Shantier de France, a ship building works on the harbor.

The chassis underneath had been designed for wealthy gentlemen to glide between country estates in perfect silence. Samson intended to drive it straight at German cavalry patrols. The result looked absurd. A luxury motorc car wrapped in gray steel with a machine gun mounted on top, crewed by sailors who had never fought on land.

Within weeks, a growing flatillaa of these improvised vehicles were harrying German positions between Dunkirk and Antworp. Within months, the Admiral Ty ordered a standardized version with a fully rotating turret. Within years, that vehicle would fight across Egypt, Arabia, and East Africa. And when the next World War began a quarter of a century later, it would still be fighting almost unchanged in the same deserts.

Almost no other armored vehicle came close to matching that service record. The Rolls-Royce armored car was never supposed to exist. Born from desperation and improvisation rather than any military plan, it became one of the longest serving armored fighting vehicles of the 20th century. In the opening weeks of the war, the Western Front was still mobile.

German cavalry screened the advance of their infantry. probing allied lines and cutting communications. The Royal Naval Air Service had been sent to Dunkirk to protect British airfields and rescue downed pilots. But Samson recognized a broader opportunity. Motorcars armed with machine guns could perform the reconnaissance and raiding role the cavalry had owned for centuries, but faster with greater range and with heavier firepower.

On the 4th of September, Samson’s brother, Felix, had proved the concept by mounting a Maxim gun on an unarmored touring car and ambushing a German vehicle near Cassell. The attack worked, but the lack of any protection meant that a single rifle bullet could kill the driver and stop the car dead.

An armed vehicle without armor was a weapon you could use exactly once. That said, Samson’s improvised 6 mm boiler plate was not real armor. It stopped rifle bullets at range, but at closer distances, a standard infantry round could punch straight through. It was better than nothing, barely. The British army wanted nothing to do with the idea.

The War Office considered armored motor vehicles a novelty with no doctrinal future. Senior naval figures were barely more enthusiastic, with fourth sea lord Cecil Lambert reportedly dismissing what he called the armored car and caterpillar nonsense. It fell instead to Winston Churchill, then first Lord of the Admiral T, to champion the concept.

Churchill authorized the formation of the Royal Naval Armored Car Division and requisitioned every available Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost chassis in the country. What Churchill understood and what the War Office missed was that the internal combustion engine had the potential to transform ground warfare as completely as it was already transforming the war at sea and in the air.

A vehicle that could move at 40 mph, carry a machine gun, and offer its crew at least some protection from enemy fire, could control roads, screen advances, and pursue retreating infantry faster than any cavalry squadron. The challenge was finding a chassis reliable enough to sustain operations over hundreds of miles without constant mechanical failure.

Most existing military trucks were too slow, too unreliable, or too fragile. The answer was to start with the most dependable chassis in the world. The selection of the Silver Ghost was no accident. Rolls-Royce had won the 1913 Alpine trial, completing 2,000 mi through the Austrian Alps without a single mechanical failure.

The company’s reputation for overengineering was documented fact, not marketing. The sixcylinder inline engine rated at 40 over 50 horsepower in Rolls-Royce’s own designation displayed 7,428 cm. In later military specification, it produced up to 80 brake horsepower at 2250 revolutions per minute. That power plant, designed for smooth, silent luxury motoring, would prove virtually indestructible when subjected to combat loads, three times heavier than anything Rolls-Royce had intended.

By October 1914, an Admiral T design committee led by flight commander TG Heatherington had produced a standardized armored body. William Beardmore and Company of Glasgow manufactured 12mm rolled steel armor plates riveted to a light internal frame and fitted over the ghost chassis. A fully rotating turret sat on a ball bearing race on top, allowing the gunner to traverse smoothly through 360° even on uneven ground.

The turret mounted a single watercooled Vicar’s machine gun in 303 caliber, firing at between 450 and 600 rounds per minute from 250 round canvas belts. A crew of three operated the vehicle. The driver sat at the front behind an armored windscreen with a narrow vision slit. The gunner stood in the turret working the vicers.

The commander directed both. Fitting nearly a ton of steel plate to a chassis built for a 1 and 1/2 ton luxury body required careful weight distribution. The designers concentrated the heaviest armor at the front and around the turret ring with thinner plate protecting the sides and rear. Dual rear wheels compensated for the load and the four-speed manual gearbox, though stressed, proved reliable.

The first three-purpose built 1914 patent vehicles were delivered on the 3rd of December. Each weighed approximately 4 and 3/4 tons combat loaded. Top speed on hard surfaces reached 45 mph. Operational range stretched to 150 mi, but timing betrayed the design. By late 1914, trench warfare had frozen the Western Front solid.

Cars built for open roads were useless against barbed wire and artillery. Most were withdrawn to coastal defense or reassigned to quieter theaters. In August 1915, the armored car squadrons transferred from naval to army control. The Rolls-Royce needed a different kind of battlefield. It found one in the desert. The vehicle evolved through the interwar years.

Rather than being replaced, the 1920 pattern introduced thicker radiator armor, solid disc wheels, replacing vulnerable wire spokes, and loud radiator shields to reduce overheating. The Mark 1 variant added a commander’s cupella with 15 constructed. Armored bodies were assembled at Woolitch Arsenal. A complete redesign in 1924 produced 24 vehicles with a smaller turret, permanent cupiller, and distinctive anti-bullet splash rails across the bonnet.

According to British Army infantry records cited by the tank museum at Bovington, 76 Rolls-Royce armored cars remained in active service on the 1st of September 1939. Vehicles designed before the SO were still on the front line when Germany invaded Poland. Now, before we get into the combat record that turned this vehicle into a legend, if you are enjoying this deep dive into British engineering, consider subscribing.

It takes a second and it costs nothing. Now, back to the place this machine was built for, even if nobody knew it yet. Egypt, 1916. The western desert, where temperatures climbed past 50° C and sand stripped paint from steel, became the proving ground the Rolls-Royce had been waiting for.

Major Hugh Grovener, the second Duke of Westminster, commanded a light armored car brigade of 12 Rolls-Royces. On the 26th of February, six of his cars fought at the battle of Agardia, helping to crush the main Senusi tribal force and capture their leader, Ga Pashia. Three weeks later came the mission that entered military folklore.

92 British sailors from HMS Tara, torpedoed by a German submarine, were being held in deteriorating conditions deep in the Libyan desert. Westminster assembled a rescue column of nine armored cars, 26 supply tenders, and 10 ambulances. They drove 120 mi into hostile territory. The Susi guards took one look at the approaching armored cars and fled.

Every prisoner was recovered alive. According to contemporary accounts, the roundtrip covered 250 mi through open desert in 22 hours without a single British casualty. Grateful survivors later presented Westminster with a silver model Rolls-Royce armored car. The Rolls-Royce also served in German East Africa where Lieutenant Commander W.

Whittle squadron supported operations against Paul Vonletto Vorbeck’s forces. German Assari, according to accounts collected after the war, called the armored cars the charging rhino which spits lead. At Gallipoli, RNAS armored car crews used their vicar’s guns to lay down covering fire during the landings at said Elbar in April 1915, though the cars themselves may not have made it onto the beaches.

In Russia, Commander Oliver Locker Lampson led a force of Rolls-Royces across the Eastern Front, Galissia, Romania, and the Caucusesus. Reportedly achieving record-breaking mileage with almost no mechanical failures. Wherever the war was still mobile enough for wheeled vehicles, the car performed. Te Lawrence’s experience elevated the vehicle from effective to legendary.

After capturing a Cara in July 1917, Lawrence requested Rolls-Royce cars for operations against Ottoman railway lines. He received nine silver ghosts, five armored and four unarmored tenders, commanded by lieutenants Gilman and Wade of the Hedge armored car battery. Lawrence’s personal tender, which he named Blue Mist, became perhaps the most famous military vehicle of the war.

In his memoir, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence described the car’s speedometers, touching 65 mph despite months of desert work with only basic running repairs. When Blue Mist’s rear leaf springs snapped after a railway demolition in September 1917, Lawrence shot aboard in two with his pistol, roped the improvised wooden splint to the broken suspension, and did the ordinary work with the car for the next 3 weeks. The repair held.

Over a year later, on the 2nd of October 1918, Lawrence rode into Damascus in a Rolls-Royce. His verdict, written in seven pillars, became the vehicle’s epitth. A roles in the desert, he declared, was more valuable than rubies. When asked after the war what single gift he would most value, Lawrence replied that he should like his own Rolls-Royce car with enough tires and petrol to last all his life.

From a man who had been offered kingdoms, that was the highest compliment any machine could receive. The inter war decades should have killed the design. Every other armored vehicle from World War I was scrapped or relegated to museums. The Rolls-Royce survived because it perfectly matched Britain’s imperial strategy.

At the 1921 Cairo conference, Churchill and Air Marshall Trench had agreed that RAF armored car companies were cheaper than permanent army garrisons for policing vast colonial territories. A vehicle designed for the mobile warfare of 1914 proved ideal for desert patrol operations 20 years later. Fast enough to chase tribal raiders across open ground.

Reliable enough to operate hundreds of miles from any workshop. Armed well enough to suppress anything short of a conventional army. In Palestine, number two armored car company helped quell the Arab revolt between 1936 and 1939. In Aiden, Rolls-Royces patrolled the hinterland despite the notable vulnerability of their unarmored floor plates to buried mines.

And critically, a war office starved of interwar funding was content to keep refitting a proven design rather than spending money on a new one. The result was that when war came again in 1939, Britain’s frontline reconnaissance units in Egypt were equipped with armored cars older than most of their crews.

On the 10th of June 1940, Italy declared war. The 11th Hous stationed in Egypt held 34 Rolls-Royce armored cars, every one of them at least 15 years old. These had been modified with open topped turrets, boys anti-tank rifles in 0.55 caliber, bren light machine guns, wireless sets, and smoke grenade launchers.

Crew had increased from 3 to four. What followed astonished everyone. Within 48 hours of war breaking out, 11th Houses crossed into Libya and returned with approximately 70 Italian prisoners and no British casualties. On the 14th of June, they captured Fort Madelena without firing a shot. 2 days later they fought the first armored engagement of the Western Desert campaign, knocking out three Italian L333 tankets.

Their most remarkable catch came when patrols intercepted General Ramolo Lstuchi, engineer and chief of the Italian 10th Army along with his staff car and detailed maps of Bardia’s defenses. According to one popular regimental account, two lady friends were also found in the vehicle. The campaign climaxed at Beaom in February 1941.

Lieutenant Colonel John Comb of the 11th Hous led a mixed force of armored cars, an RAF armored car unit, and the second rifle brigade, roughly 2,000 men in total, on a 124 mile dash through what veterans described as the worst desert they had ever seen. Comb’s force reached the blocking position with 30 minutes to spare before the first retreating Italian columns appeared.

The result was the complete destruction of the Italian 10th Army. 25,000 prisoners and over 100 tanks captured. Meanwhile, in Iraq, where rebel forces besieged RAF Habania in April 1941, 18 Rolls-Royces of number one armored car company helped defend the airfield. These vehicles sat on chassis built during the previous war, making them nearly 30 years old.

Three of them, named Lion, ADA, and Astra drove under direct fire to recover a downed bomber crew. They completed the mission and returned. The Rolls-Royce was not the best armored car of either war by any technical standard. Germany’s light reconnaissance vehicles from the mid1 1930s mounted 20 mm autoc cannons effective at ranges where the vicar’s machine gun was useless.

German armor thickness reached 14 1/2 mm on lighter models and up to 30 mm on later designs with all-wheel drive configurations that the two-wheel drive Rolls-Royce could not match for crosscountry mobility. By 1943, Germany fielded armored cars with 50 mm guns capable of destroying medium tanks.

Against any of these, the Rolls-Royce was from a different era entirely. The Americans offered no true comparison. The United States did not field a purpose-built armored car until the M8 Greyhound entered service in 1943, mounting a 37 mm gun with 25 mm of armor. Britain had been operating armored cars for 29 years before America produced its first dedicated design.

But reconnaissance is not about winning firefights. It is about finding the enemy, reporting his position, and surviving to deliver that report. On those terms, the Rolls-Royce remained competitive. Its road speed matched or exceeded most contemporary armored cars. Its mechanical reliability meant patrols returned when other vehicles broke down, and its decades of desert service meant crews knew the machine intimately, ringing performance from it that no specification sheet could predict.

The real explanation for the vehicle’s longevity lay in its civilian foundation. The Silver Ghost chassis was not built to a military specification drafted by a procurement committee working to a budget. It was built to be the finest motorcar in the world with engineering tolerances that exceeded anything the military demanded.

That standard aimed at refinement and reliability rather than military expediency translated into a combat vehicle that rarely broke down, even under conditions that destroyed purpose-built military alternatives. The Crossley armored car, designed specifically for colonial service, overheated in desert temperatures that the Rolls-Royce handled without difficulty.

Sand that clogged the Crossley’s engine ran through the Ghost’s generous mechanical clearances. The difference between a chassis engineered for perfection and one engineered to a price showed itself across decades of hard use. War correspondent WT Massie, writing in the Times in December 1916, reported that not a single Rolls-Royce engine had suffered a breakdown during desert operations.

That claim, if accurate, is extraordinary for any vehicle, let alone one carrying armor through the Sahara. Replacement came in stages through 1941. South African Marman Harrington vehicles arrived first, then Humber armored cars with 37 mm guns and finally the Dameler, mounting a 2 lb of 40 mm cannon and carrying 16 mm of purpose-built armor.

The Dameler was the true generational successor. A vehicle designed from the outset for the war it was fighting. Yet, the Rolls-Royce refused to disappear entirely. In Ireland, the 13 vehicles transferred to the Free State in 1922 had served throughout the Civil War. The most famous sleeve nemon was present at Bale Nablau on the 22nd of August 1922 when Michael Collins was killed.

Its vicar’s gun jammed during the ambush. A bitter irony for a vehicle renowned for reliability. All 13 Irish cars served continuously until 1944. Withdrawn only when wartime tire shortages made operation impossible. 12 were auctioned in 1954 for between 27 and £60 each. One was preserved.

Slave Nemon was fully restored in 2011. It still fires its Vicar’s gun annually and drives under its own power. The Irish Defense Forces recognize it as the world’s oldest serving armored vehicle. At the tank museum in Bovington, a second surviving Rolls-Royce sits in the permanent collection. Built in Derby in 1920, armored at Woolitch Arsenal, it served in Ireland, then Shanghai, then Egypt, then patrolled the Norfolk coast during World War II.

In 1997, it carried Queen Elizabeth II as a passenger during a royal visit. It is insured for 2 million pounds. It still runs. Think back to that Dunkirk shipyard. A naval officer acting on his own initiative. Bolting scrap steel to a luxury car because nobody in the British military establishment believed armored vehicles had a future.

That improvisation led to a production run across three evolving patterns. 30 years of continuous frontline service across two world wars and combat operations on every continent where the British Empire fought. T Lawrence captured the achievement perfectly. In seven pillars of wisdom, he wrote three words that served as both verdict and epitap.

Great was Rolls and Great was Reus. Two vehicles still running more than a century later prove he was

News

Why German Generals Said Patton’s ApacheSoldiers Were Worse Than Hell D

In the summer of 1943, the Mediterranean sun was an unforgiving hammer beating down on the shores of Sicily….

They Laughed at the “Tea-Drinking Soldiers” — Until the British Showed Them How to Survive D

June 7th, 1944. Morning light cuts through the smoke drifting across Normandy’s hedgeros. Sergeant Bill Morrison of the 29th…

USS Carmick Fired 1,127 Shells In One Hour To Save Omaha Beach D

On June 6, 1944, General Omar Bradley stood aboard the cruiser Augusta 12 miles off the coast of Normandy…

Japanese Thought They Surrounded Americans — Then Marines Wiped Out 3,200 of Them in One Night D

July 25th, 1944. The Fonte Plateau, Guam. In the thick tropical darkness, 3,200 Japanese soldiers moved through the jungle…

Germany Stunned by America’s M18 57mm Recoilless—And Their Panzerfaust Was Outranged D

Vasil, Germany, March 24th, 1945 0900 hours. And Private Firstclass Donald Wagner of the 17th Airborne Division’s 513th parachute…

Germans Never Expected M18 Hellcat Tank Destroyers To Outrun Their Panzers D

September 19th, 1944. 0730 hours. Bison La Petite, Lorraine, France. The morning fog hung thick across the French countryside…

End of content

No more pages to load