On the afternoon of September 14th, 1944, the tropical sun hung mercilessly over the dense jungle canopy of Paleu Island, where temperatures soared past 115° Fahrenheit in the shade. Sergeant William Billy Hartman of the First Marine Division crouched behind a limestone ridge, his throat parched, his uniform soaked through with sweat, staring at what appeared to be nothing more than an impenetrable wall of green vegetation stretching across the coral ridges ahead.

For 3 days, his unit had been pinned down by precise fire from positions they simply could not locate, losing seven men to an enemy that seemed to materialize from the rocks themselves and vanish just as quickly. What Hartman and his fellow Marines did not yet know was that within the next 4 hours, a seemingly insignificant observation about broken glass would transform their impossible situation into one of the most remarkable tactical victories of the Pacific campaign.

The method they would develop that afternoon would be studied at militarymies for decades to come. And it would begin with something as simple as sunlight reflecting off a shattered lens. Before we dive into this story, make sure to subscribe to the channel and tell me in the comments where you’re watching from. It really helps support the channel.

This is the story of how a frustrated young Marine’s moment of clarity led to the development of a detection technique that would neutralize 87 concealed positions in a single afternoon. Fundamentally changing how American forces approached one of their most dangerous challenges in the Pacific theater.

The island of Paleu was supposed to be a 4-day operation. Military planners had assured the Marine commanders that resistance would crumble quickly once American forces established a beach head. What they had not anticipated was the revolutionary defensive strategy that the Japanese forces had implemented across the island’s coral ridges and limestone caves.

Gone were the desperate frontal charges that had characterized earlier engagements. Instead, the defenders had spent months constructing an intricate network of fortified positions. Each one carefully camouflaged and connected by underground tunnels that allowed fighters to appear, engage, and disappear before American forces could even identify where the threat had originated.

Private First Class Thomas Riley, a 20-year-old from Boston who had joined the Marines after his older brother had been declared missing in action in Europe, kept a journal during those first terrible days on Paleu. His entry from September 12th captured the frustration that had settled over the American forces like a suffocating blanket.

He wrote that they could hear them, could feel the rounds snapping past their heads, but they might as well have been fighting ghosts. He noted that Corporal Martinez had been hit that morning, taken down by fire from a position they had cleared twice already. The men were starting to believe the island itself was trying to end them. The Japanese defensive network on Pleu represented something entirely new in the Pacific conflict.

Colonel Kuno Nakagawa, the commander responsible for the island’s defense, had studied previous engagements with meticulous care. He understood that traditional defensive tactics had consistently failed against American firepower and air superiority. His solution was elegant in its simplicity. Rather than meeting the Americans in open confrontation, his forces would become one with the terrain itself.

Every cave, every crevice, every fold in the coral ridges was transformed into a potential fighting position. Firing ports were constructed to be barely visible, often no larger than a man’s fist, positioned to provide overlapping fields of coverage while remaining virtually invisible to observers at ground level. Sergeant Hartman had been a marksman instructor at Camp Pendleton before being assigned to the Pacific.

He understood optics, understood the mathematics of trajectory and the art of concealment, but nothing in his training had prepared him for an enemy that could fire from positions that even after the shot remained undetectable. On the morning of September 14th, he gathered his remaining team members in a shallow depression behind the limestone ridge that had become their temporary refuge.

There was Private First Class Riley, the young Bostononian with the journal. There was Corporal James Jimmy Washington, a former hunting guide from Montana who had grown up tracking elk through mountain terrain. And there was Lance Corporal David Kowalsski, a Polish American from Chicago, who had worked as a photographers’s assistant before the conflict and understood light in ways that would prove crucial to what followed.

Hartman addressed his team in a low voice, explaining that they had lost too many men to an enemy they could not see. He stated that headquarters wanted them to advance, but advancing meant walking into fire they could not suppress. He told them they needed to find another way and asked if any of them had ideas, any observation, anything at all that might help them understand what they were dealing with.

For a long moment, no one spoke. The distant sound of artillery rolled across the ridges like thunder. Then Kowalsski shifted position, squinting toward the jungle covered slopes ahead. He mentioned that he had noticed something strange that morning. He said that just before dawn when he had been on watch, he had seen a flash just for a second from one of those positions they had marked as cleared.

He noted it was not a weapon flash, but something else like light bouncing off glass. Hartman’s eyes narrowed with interest. He asked Kowalsski to tell him exactly what he saw. Kowalsski explained that the sun was just coming up over the eastern ridge and for maybe 2 or 3 seconds there was this glint, this reflection from what looked like solid rock.

He added that he had thought he was seeing things, that he was exhausted and maybe imagining it, but then it happened again and he had marked the position in his mind. Washington, the Montana hunter, leaned forward with sudden intensity. He said he knew what that was. He explained that back home when he was tracking game, sometimes you could spot a deer in the brush because of how light caught their eyes.

He suggested that if someone had optics up there, binoculars or a rifle scope, and the glass was damaged, or even just angled wrong, the early morning light would catch it. The realization hit Hartman like a physical force. For days they had been searching for positions that were invisible to the naked eye. But no amount of camouflage could completely hide the one thing every observation post required, a way to see out.

And seeing out meant glass, and glass, no matter how carefully concealed, would interact with light in ways that vegetation and rock never could. Hartman felt his heart begin to race, but he kept his voice calm as he worked through the implications. He said that if they had optics at every position and they had to have optics to be hitting them with such accuracy, then every position had glass.

He continued that damaged glass, glass that was scratched or cracked from near misses or the concussion of explosions, would scatter light differently than intact glass. He concluded that if they could systematically scan for those reflections at the right time of day when the sun was at the right angle, they might be able to map positions that were otherwise invisible.

Private Riley raised a practical concern. He pointed out that they could not just stand out in the open scanning the ridges as they would be hit before they spotted anything. Hartman was already thinking through the solution. He said they would not be standing and they would not be in the open. He explained that they would use the terrain against them, set up observation points where they had cover, but could still see the slopes when the light was right.

He noted that early morning, late afternoon, those were their windows. He added that the sun would be low enough to create horizontal light that would catch any glass facing their direction. What happened next would become one of the most methodical and effective counterconcealment operations of the Pacific campaign. Hartmann divided his small team into two observation groups, positioning them at opposite ends of the limestone ridge, where natural depressions provided cover while still allowing a view of the jungle covered slopes ahead. Each team was equipped

with binoculars and a detailed map of the terrain divided into a grid system that Hartman sketched out using the coordinates they had already established. The first systematic scan began at 1700 hours when the afternoon sun had dropped low enough to send horizontal rays across the western face of the ridge complex.

For the first 20 minutes they saw nothing unusual, just the endless green of the jungle canopy, the gray white of exposed coral, the deep shadows of cave entrances that might or might not conceal threats. Then Kowalsski, whose photographers’s eye had first noticed the phenomenon, spotted it.

He called out in a low voice that he had contacted grid reference Charlie 7, reporting a definite glass reflection approximately 200 m out, elevation maybe 20 m above their position. Washington confirmed the sighting, adding that he was marking it now, and noting that it looked like it was in what they thought was solid rock face.

Over the next 40 minutes, as the sun continued its descent, the team identified and marked 11 additional positions. Each one appeared as nothing more than a brief flash, a momentary glint that lasted perhaps 2 or 3 seconds before the angle of light shifted and the reflection disappeared. Without knowing exactly when and where to look, these flashes would have been invisible, lost in the general shimmer of a tropical afternoon.

But with systematic observation and careful documentation, patterns began to emerge. Hartman compiled the data from both observation teams that evening, cross-referencing the marked positions against their existing maps. What he discovered was both alarming and encouraging. Of the 12 positions they had identified that afternoon, eight were in locations that had been designated as cleared after previous sweeps.

The Japanese defensive network was far more extensive than anyone had realized. But now, for the first time, they had a method for revealing it. The following morning, Hartman requested an audience with Captain Robert Morrison, the company commander, who had been struggling to advance his forces against the invisible resistance.

Morrison was a veteran of Guadal Canal, a pragmatic officer who had learned to value the observations of experienced enlisted men. When Hartman explained what his team had discovered, Morrison listened with increasing interest. Hartman laid out the intelligence he had gathered, explaining that his team had identified 12 concealed positions using reflected light from optical equipment.

He noted that eight of those positions were in areas they had already cleared, meaning the enemy was reoccupying or had never actually vacated. He proposed expanding the technique using multiple observation teams coordinated across the company front, scanning during optimal light conditions in the morning and evening.

Morrison studied the marked map for a long moment. Then he asked how confident Hartman was that those reflections indicated occupied positions and not just debris or natural mineral formations. Hartman acknowledged that he could not be 100% certain, but explained his reasoning. He said that the reflections were appearing in locations that matched the pattern of fire they had been receiving.

He added that the positions made tactical sense with good fields of observation, cover, and likely connections to the tunnel network they knew existed. He concluded that even if some were false positives, confirming and neutralizing the legitimate positions would fundamentally change their situation. Morrison made his decision with the speed of a man who had been waiting for any viable solution.

He approved the expansion, telling Hartman to coordinate with the other squad leaders, standardize the observation protocol, and provide a comprehensive target list by 1,800 hours. He said that if this worked, it would be reported up the chain immediately. What followed was an unprecedented coordination effort.

Hartman spent the morning hours training other squad leaders in the observation technique, emphasizing the critical importance of timing, patience, and systematic grid scanning. He explained that they were not looking for obvious positions or movement, but for a specific phenomenon that would only be visible under certain conditions.

Corporal Washington, drawing on his hunting experience, added crucial refinements to the technique. He explained that a glint from undamaged glass would be sharp and clean like a mirror flash. But what they were mostly seeing was different, more scattered and diffuse, which meant damaged glass lenses that had been cracked by near misses or the constant concussion of artillery.

He said that damaged glass scattered light in multiple directions, which actually made it easier to spot because the reflection lasted longer and was visible from a wider angle. Private Kowalsski contributed his understanding of photographic optics, explaining how different types of glass would interact with light at different angles.

He noted that a binocular lens, which was slightly convex, would reflect differently than a flat rifle scope lens. He added that by paying attention to the character of the reflection, they might be able to determine what type of equipment was at each position. By,400 hours, Hartman had briefed six additional squad leaders and established a coordinated observation network spanning nearly 800 m of the American front line.

Each observation team had been assigned specific grid sectors to monitor with overlapping coverage to ensure no area was missed. Communication runners were positioned to relay sightings to a central compilation point where Hartman and Captain Morrison would build a comprehensive target map. The afternoon scan began at 16:30 hours.

The conditions were nearly perfect as thin clouds diffused the direct sunlight while still allowing sufficient illumination for reflections to be visible. Across the American line, Marines crouched in their observation positions, binoculars pressed to their eyes, scanning their assigned grid sectors with the patience of men who understood their lives depended on thoroughess.

The first confirmed sighting came at 1642 from an observation team 300 m to Hartman’s left. The runner arrived breathless with the report of a definite glass reflection at grid reference echo 12. Estimated distance 350 m positioned in what appeared to be a natural rock formation. Within the next hour, reports came flooding in from across the front.

Each one was logged, plotted, and cross- refferenced against known terrain features and previous engagement patterns. By 18800 hours, when the light had shifted too far west to continue effective observation, Hartman’s compiled map showed 43 confirmed or suspected positions across the company’s front. The density was staggering.

In some areas, concealed positions were spaced barely 20 m apart, creating overlapping fields of observation and fire that explained why previous advances had been so costly. Captain Morrison studied the completed map with an expression that mixed satisfaction with grim understanding. He observed that they had been walking into a prepared engagement zone, and noted that no wonder they had been taking such heavy casualties.

He said that with this intelligence they could finally do something about it. The next phase of the operation required careful coordination with supporting elements. Morrison submitted a request for preparatory support against the identified positions providing precise coordinates derived from the observation data.

The request emphasized that the targets were hardened positions requiring direct approaches rather than general area coverage. The morning of September 15th dawned with the same oppressive heat that had characterized every day on Pleu. But for the Marines of Hartman’s company, this morning felt different. For the first time since landing on the island, they had actionable intelligence about what they faced.

They knew where the hidden positions were, or at least where many of them were. The advantage of invisibility that had made the Japanese defensive network so effective had been significantly reduced. The preparatory phase began at 0700 hours and lasted 45 minutes. When it concluded, Hartman led his observation team in another scan, this time looking not for new positions, but for evidence of which identified positions had been affected. The results were encouraging.

Several positions that had shown clear glass reflections the previous day now showed nothing, suggesting their optical equipment had been compromised or the positions had been abandoned. But the true test came when the advance began. Captain Morrison had restructured the approach based on the intelligence Hartman’s team had provided.

Rather than advancing on a broad front that would expose his Marines to multiple concealed positions simultaneously, he organized a methodical approach that isolated and addressed identified positions one at a time. The difference was immediate and dramatic. Private Riley, advancing with the first element, later wrote in his journal about that morning’s operation.

He noted that it was like someone had turned on the lights. He explained that before they had been moving forward into nothing they could see, just waiting to be hit from somewhere they could not identify. But that morning they knew where to look. He described how when they approached a position they had marked, they could actually see the firing port, this tiny dark slit in what looked like solid rock.

He reflected that they must have walked past a dozen just like it in the previous days, without ever knowing they were there. The advance that morning covered ground that had been unreachable for 3 days. By noon, 31 of the 43 positions identified through the glass reflection method had been confirmed and addressed. The remaining positions either had been abandoned or were found to contain equipment that had been rendered inoperable by the preparatory phase.

But Hartman was not satisfied with a single day’s accomplishment. He understood that the Japanese defenders would adapt, would find ways to counter the technique if given time. That afternoon, he convened his observation team to discuss refinements and anticipate enemy countermeasures. He explained to his team that they had to assume the opposing forces would figure out what they were doing.

He said they needed to think about how they would counter this technique if they were in the enemy’s position and then get ahead of those counter measures. Washington offered the first insight, suggesting that if he were the enemy, he would start covering his optics when he was not actively using them.

He noted that a cloth cover or even a piece of vegetation over a lens would eliminate the reflection entirely. Kowalsski agreed and added another consideration. He pointed out that they might also adjust their positioning, angling their optics so they never face directly toward the American lines. He explained that if their lenses are pointed slightly away, the reflection would go in a different direction and the Americans would never see it.

Hartman nodded, acknowledging these possibilities. He then proposed their counter counter measures. He suggested that for covered optics, they needed to catch them during active observation periods when the covers would have to be removed. He noted this meant more frequent scans, not just morning and afternoon, but throughout the day, looking for brief windows of exposure.

For angled optics, he proposed using multiple observation points at different angles, explaining that even if a position was invisible from one angle, it might be visible from another. Over the following days, the technique was refined and expanded. Hartman established a rotating observation schedule that maintained continuous coverage during daylight hours.

He trained additional teams in the method, emphasizing the importance of patience and systematic scanning. He developed a standardized reporting format that allowed rapid compilation and analysis of sighting data. The results exceeded anything the Marines had anticipated. In the week following the initial implementation of the glass reflection method, Hartman’s company identified and addressed over 200 concealed positions across their sector.

Casualties dropped by more than 60% compared to the previous week. The psychological effect on the Marines was perhaps even more significant than the tactical advantage. For the first time, they felt they were facing an enemy they could see, an enemy they could understand and overcome. Word of the technique spread rapidly through the marine units on Pleu.

Captain Morrison’s afteraction reports detailed the method and its results, leading to implementation across the divisional front. Other units began reporting similar accomplishments, adapting the basic technique to their specific terrain and conditions. Sergeant Hartman was summoned to regimental headquarters on September 20th to brief senior officers on the method.

Standing before a room of colonels and majors, the enlisted marine from California explained the principles of the glass reflection technique with the same clarity he had used to train his own squad. He began by stating that the method was based on a simple optical principle, explaining that glass reflects light differently than natural materials and damaged glass reflects it even more distinctly.

He continued that by systematically scanning at optimal light angles, typically early morning and late afternoon, they could identify concealed positions that were otherwise invisible. He noted that the key elements were timing, patience, systematic coverage, and immediate documentation of sightings. One colonel, who had been struggling with similar concealment challenges in his own sector, asked about the limitations of the technique.

He wanted to know what happened when weather conditions were not optimal or when the enemy adjusted their tactics. Hartman responded thoughtfully, acknowledging that overcast conditions reduced effectiveness, but noting that even diffuse light could produce identifiable reflections from damaged glass. He added that for enemy countermeasures, they had found that maintaining continuous observation throughout the day caught positions that were only briefly exposed.

He concluded that no countermeasure was perfect and eventually they could catch them. The briefing led to formal documentation of the technique and its dissemination across the Pacific theater. Military intelligence officers interviewed Hartman and his team extensively producing training materials that would be used in subsequent operations.

The glass reflection method, or as it came to be informally known, the broken glass method, became standard doctrine for identifying concealed positions in jungle and cave defense environments. But perhaps the most significant impact of the technique was not tactical, but psychological. For months, American forces in the Pacific had struggled against an enemy that seemed to possess almost supernatural abilities of concealment.

The frustration and fear generated by facing threats they could not see had taken a heavy toll on morale. The glass reflection method did not just provide a tactical solution. It restored the Marine sense of agency, their belief that they could understand and overcome the challenges they faced. Private Riley’s journal entry from September 22nd captured this transformation eloquently.

He wrote that it was strange how such a small thing could change so much. He reflected that a week ago he had felt helpless, like they were facing something they could not comprehend, let alone conquer. But now, he explained, they had a method, a way to see what was hidden, a way to respond effectively. He concluded that the enemy was still out there, still dangerous, but they were not invisible anymore, and that made all the difference in the world.

The campaign for Pleu would continue for another 2 months, far longer than the 4 days initially predicted. The cost was high with casualties numbering in the thousands on both sides. But the glass reflection method developed by a sergeant and his small team in the desperate hours of September 14th saved countless lives and contributed to the eventual completion of the operation.

Sergeant William Hartman survived the campaign and was awarded the Bronze Star for his contribution to tactical intelligence. He returned to the United States in early 1945 and was assigned to the Marine Corps Training Command where he spent the remaining months of the conflict teaching the observation techniques he had developed on Pleu to the next generation of Marines.

Corporal James Washington, the Montana hunter, whose understanding of light and animal behavior had contributed crucial insights to the method, was wounded in late September, but recovered fully. He returned to Montana after the conflict ended and spent the rest of his life as a hunting guide, occasionally telling stories about the time his elk tracking abilities had helped turn the tide on a Pacific island he had never heard of before, 1944.

Lance Corporal David Kowalsski, the photographers’s assistant whose initial observation had sparked the entire development, pursued his passion. After returning home, he became a successful commercial photographer in Chicago, specializing in architectural work that required the same understanding of light and reflection that had served him so well during the Pacific campaign.

Private First Class Thomas Riley, the young Bostononian whose journal entries documented the development of the technique, was reunited with his older brother after the conflict ended. His brother had been held as a prisoner in Europe and was liberated in April of 1945. Thomas kept his journal for the rest of his life, eventually donating it to a military history archive where it became a primary source for historians studying the Pacific campaign.

The glass reflection method itself evolved and was refined in subsequent conflicts, adapted to new environments and new technologies. The basic principle that concealment is never perfect and that systematic observation under optimal conditions can reveal what is meant to be hidden remained constant. Modern surveillance techniques, while vastly more sophisticated, still incorporate elements of the approach developed by Hartman and his team on that sweltering afternoon in September of 1944.

Looking back on the events of those days, what stands out is not just the tactical innovation, but the human qualities that made it possible. Curiosity, the willingness to question assumptions and notice anomalies. Collaboration, the combining of different experiences and perspectives to develop a comprehensive solution.

Persistence, the determination to find an answer when the obvious approaches had failed, and adaptability, the ability to refine and improve the method in response to changing conditions and enemy countermeasures. These qualities, more than any specific technique or technology, were what ultimately determined the outcome of the Pacific campaign.

The conflict was not won by superior firepower alone, though American industrial capacity certainly played a crucial role. It was won by the ability of individual marines, soldiers, sailors, and airmen to think, to adapt, and to find solutions to problems that seemed insurmountable. The broken glass method stands as a testament to that capacity for innovation under pressure.

What began as a frustrated observation by a young photographers’s assistant became a systematic technique that saved hundreds of lives and contributed to the eventual victory. It is a reminder that in any conflict, the most valuable weapons are not always the most powerful or the most advanced.

Sometimes the most valuable weapon is simply the ability to see what others have missed. The coral ridges of Pleu are quiet now. The jungle has reclaimed much of the terrain that was contested so fiercely in the autumn of 1944. But the lessons learned there, the techniques developed by men like Hartman, Washington, Kowalsski, and Riley continue to influence military thinking to this day.

The principle that careful observation, systematic analysis, and creative thinking can overcome even the most sophisticated concealment remains as valid now as it was on that September afternoon when a glint of light off broken glass changed everything. And that concludes our story. If you made it this far, if you made, please share your thoughts in the comments.

What part of this historical account surprised you most? Don’t forget to subscribe for more untold stories from World War II and check out the video on screen for another incredible tale from history.

News

Why the Viet Cong Feared the SAS More Than Any American Unit

Fuaktui Province, South Vietnam, March 17th, 1966. The Vietkong sentry never heard them coming. Nuan Vanam had survived 2…

They Mocked His “Backwards” Loading Method — Until His Sherman Destroyed 4 Panzers in 6 Minutes D

At 11:23 a.m. on September 19th, 1944, Private First Class Walter Kowalsski crouched inside his M4 Sherman tank near…

The Most Insane Helicopter Pilot of Vietnam – Ace Cozzalio D

Oh, good girl. You want to hear the story about the deadliest IHOP employee to have ever existed? Yeah….

Why American Soldiers Started Killing Their Own Officers in Vietnam D

Today’s video is brought to you by the good people over at AG1. I told myself I wasn’t doing…

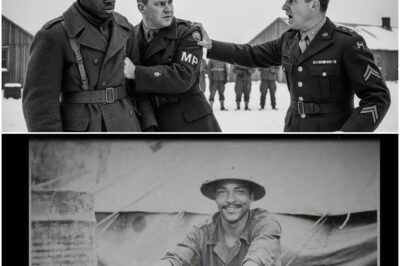

How Canadians Stood Up for Black GIs After U.S. MPs Crossed the Line D

July 1944, Aldershot, England. The summer air hung thick and warm inside the Red Lion Pub. Canadian soldiers sat…

The Ugly Gun That Beat the Beautiful Thompson: M3 Grease Gun’s WWII Revolution D

October 1942, a General Motors Inland Division in Dayton, Ohio, George Hyde, a 52-year-old immigrant from Germany, was completely…

End of content

No more pages to load