November 8th, 1943. Corporal Teeshi Morimoto crouched in the dense undergrowth of Bugganville’s jungle. His Type 38 rifle clutched against his chest. The humidity pressed down like a wet blanket. And somewhere in the green darkness ahead, the Americans were waiting. He had trained for this moment for three years, memorized every tactic in the Imperial Army’s infantry manual, practiced bayonet charges until his hands bled.

He knew exactly what to expect from American rifles, their effective range, their rate of fire, their penetration capabilities. What he did not know, what no amount of training had prepared him for, was the sound that would shatter the morning silence 30 seconds later. A sound like thunder compressed into a single devastating roar.

A sound that would haunt him for the rest of his life. Before we jump back in, tell us where you’re tuning in from. And if the story touches you, make sure you’re subscribed because tomorrow I’ve saved something extra special for you. The weapon that made that sound was not supposed to exist on a modern battlefield.

According to everything Teeshi had been taught at the Kumamoto infantry school, shotguns were relics of a bygone era. hunting implements ills suited for military engagement. His instructors had dismissed them with contempt during lectures on enemy armaments. Too short in range, they said, too limited in ammunition capacity, too crude for the precision demands of contemporary warfare.

The Americans might carry them, his training officer had acknowledged, with a dismissive wave, but only as secondary weapons for guards and military police, never as primary combat arms. No serious military force would deploy shotguns in frontline assault operations. It was unthinkable. It was barbaric.

It was, as Teeshi would discover, in the most visceral way possible, devastatingly effective. The Imperial Japanese Army’s understanding of American shotgun capabilities stemmed from a combination of outdated intelligence, cultural bias, and a fundamental misreading of American tactical doctrine.

Japanese militarymies had devoted countless hours to studying American equipment. From the M1 Garand rifle to the Browning automatic rifle, from tank specifications to artillery ranges. Students like Teeshi had memorized technical specifications with the dedication of monks studying sacred texts. They could recite the muzzle velocity of an American Springfield rifle, estimate the effective range of a Browning machine gun, calculate the penetration depth of various caliber rounds through different materials.

But the shotgun received barely a footnote in their education relegated to a brief mention in a section on obsolete weaponry that modern armies had wisely abandoned. This dismissive attitude reflected deeper assumptions about the nature of modern warfare. The Japanese military doctrine of the 1940s emphasized precision marksmanship, disciplined fire control, and the rifle as the infantry men’s primary tool.

Officers preached the virtue of the well- aimed shot, the economy of ammunition, the superiority of training and discipline over raw power fire. The idea of a weapon that fired multiple projectiles in a spreading pattern that sacrificed range for devastating close quarter impact that relied on saturation rather than precision seemed almost philosophically offensive to instructors raised on Bushidto principles and German military theory.

Lieutenant Hiroshi Sakata, who taught weapons tactics at the Sendai Military Academy, exemplified this perspective in his 1942 training manual, writing that the shotgun represents the triumph of American industrial excess over marshall discipline, a weapon for those who cannot master the rifle’s demands. The few Japanese soldiers who had encountered shotguns in previous campaigns provided intelligence that reinforced rather than challenged these assumptions.

Reports from China mentioned American military advisers carrying shotguns, but always in defensive roles, guarding facilities or protecting convoys. These observations confirmed the prevailing belief that shotguns served auxiliary purposes, backup weapons for situations where the rifle proved impractical. None of these reports captured the reality of what American Marines had been developing through the brutal lessons of Guala Canal and Teroa, the tactical evolution that would transform the shotgun from a secondary arm into a primary assault

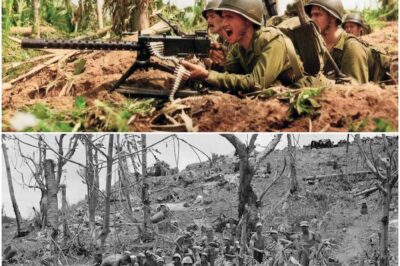

weapon for specific combat scenarios. The actual American approach to shotgun deployment had evolved through hard experience in the Pacific theat’s unique combat environment. Marine Corps leadership, unlike their more conservative army counterparts, recognized that jungle warfare and cave clearing created engagement distances that rendered rifles inefficient.

In dense vegetation where visibility extended mere feet, where ambushes erupted at arms length, where enemy soldiers emerged from spider holes in bunkers at point blank range, the traditional advantages of rifle accuracy became irrelevant. What mattered in these nightmarish close quarter battles was immediate, overwhelming stopping power.

The ability to neutralize a threat in a fraction of a second. The psychological impact of a weapon that didn’t just wound, but physically threw enemies backward. Captain James Whitmore, who commanded a marine weapons company during the Solomon Islands campaign, articulated this tactical revolution in his afteraction reports. In jungle combat, he wrote, “The engagement envelope collapses to distances where a shotgun spread pattern becomes an advantage rather than a limitation.

A rifleman must achieve precision under extreme stress at ranges of 5 to 15 ft. A shotgunner simply needs to point in the general direction of the threat. When a Japanese soldier emerges from concealment 3 ft away, the marine with a shotgun survives. the Marine with a rifle often does not. This brutal calculus led to the widespread distribution of 12 gauge and 20 gauge shotguns among marine assault units, particularly those designated for point positions and tunnel clearing operations.

The 20 gauge, in particular, found favor for its reduced recoil, lighter weight, and surprising effectiveness at the engagement distances typical of Pacific combat. While it lacked the raw power of its 12- gauge cousin, the 20 gauge could be fired faster, carried more comfortably during extended patrols, and proved quite sufficient for stopping human targets at ranges under 20 yards.

Marines loaded these weapons with buckshot shells, each containing multiple pellets that spread in a cone pattern, creating a lethal zone several feet in diameter. Japanese intelligence services, despite their sophistication in other areas, completely missed this tactical development. Their informants in neutral countries reported on American weapons production, noting increases in shotgun manufacturing, but analysts interpreted these figures as reflecting homeront sporting goods production or rear echelon security

equipment. The idea that American frontline infantry would carry shotguns as primary weapons seemed so contrary to established military doctrine that intelligence officers dismissed field reports suggesting otherwise as exaggerations or misidentifications. When a Japanese patrol on New Georgia reported encountering Marines with short-barreled weapons that produced devastating close-range effects, headquarters classified the weapons as experimental submachine guns rather than reconsidering their assumptions about

shotgun deployment. This intelligence failure had its roots in a broader Japanese underestimation of American tactical flexibility. The Imperial Army’s own doctrine emphasized standardization with each soldier carrying prescribed equipment and following established procedures. The notion that American forces might adapt their loadouts to specific mission requirements, that individual units might carry diverse weapons based on expected engagement conditions, that Marines might grab shotguns for one operation and rifles for another,

contradicted the Japanese understanding of proper military organization. Such flexibility seemed undisiplined, chaotic, inefficient. Yet, this very flexibility gave American forces a significant advantage in the varied combat environments of the Pacific theater. Training for Japanese infantry reflected this doctrinal rigidity.

Teeshi Moramoto’s experience was typical. During his three years at the Kumamoto Infantry School, he fired thousands of rounds through his type 38 rifle, practiced bayonet techniques until muscle memory took over, learned to estimate ranges, and adjust his sights accordingly. He could strip and clean his rifle blindfolded, identify malfunctions by sound, and maintain accuracy while exhausted and under stress.

He had trained against targets representing American infantrymen at ranges from 50 to 300 meters, learning to pick off enemies advancing across open ground or taking cover behind obstacles. Not once had his training included scenarios where an enemy appeared suddenly at arms length with a weapon optimized for exactly that distance.

Close quarters combat training in the Imperial Army focused almost exclusively on bayonet fighting and hand-to-hand techniques. Instructors taught that when battle reached intimate distances, the rifle with fixed bayonet became a spear, and superior spirit would overcome any American advantage in individual strength or size. Students practiced intricate thrusting techniques, parries, and buttstroke combinations.

They absorbed lectures on fighting spirit, on accepting death to achieve victory, on the moral superiority that would triumph over materialistic Americans who feared casualties. This emphasis on spiritual factors over tactical realities would prove catastrophic when Japanese soldiers found themselves facing weapons that negated all their close combat training in a fraction of a second.

The psychological preparation Japanese soldiers received regarding American combat effectiveness contained further dangerous misconceptions. officers assured their men that Americans lacked stomach for sustained close combat, that they relied on artillery and air support to avoid infantry engagements, that they would retreat when confronted with determined bayonet charges.

These assessments contained partial truths that made them more convincing. Americans did indeed rely heavily on supporting arms, did prefer to engage at longer ranges when possible, did take casualties more seriously than the Japanese high command considered appropriate. But these preferences reflected tactical sophistication rather than cowardice, and American Marines had repeatedly demonstrated willingness to engage in savage close quarters combat when circumstances demanded it.

Teeshi himself had absorbed these teachings without question. His letters home during training revealed a young man confident in his preparation. Certain that his superior training and willingness to sacrifice would overcome any American advantages in equipment or firepower. He wrote to his younger brother in March 1943, explaining that American soldiers might possess more weapons and supplies, but they lacked the spiritual strength to use them effectively in close combat.

“When we meet them with bayonets,” he predicted, they will break and run. This confidence was not mere bravado but reflected genuine belief in what his instructors had taught him, what senior officers repeated constantly. What the entire military culture reinforced through every channel of communication. Preparing and narrating this story took us a lot of time.

So if you are enjoying it, subscribe to our channel. It means a lot to us. Now back to the story. The specific conditions on Bogenville intensified these misconceptions. The island’s mountainous jungle terrain created a combat environment where engagements occurred at extremely close range, often in dense vegetation that reduced visibility to mere feet.

Japanese defensive doctrine on the island emphasized ambush tactics, using the jungle to negate American advantages in firepower and air support. Soldiers like Teeshi were trained to wait until American patrols came with an optimal range, typically 30 to 50 m, then initiate contact with concentrated rifle fire before closing with bayonets if the Americans wavered.

This approach had achieved local successes earlier in the campaign, reinforcing Japanese confidence in their tactics. What Japanese commanders failed to appreciate was that American forces were simultaneously adapting their own tactics based on these same engagements. Marine leaders recognized that their standard rifle-based tactics proved inefficient in Bogenville’s jungle environment.

They began assigning shotguns to point men, the soldiers who walked ahead of patrols and typically made first contact with the enemy. They trained these Marines in aggressive immediate action drills that emphasized overwhelming violence of action in the first seconds of contact. They developed techniques for using shotguns in combination with grenades in automatic weapons to create devastating effects in close quarters ambushes.

Sergeant Robert McKenzie, who carried a 20- gauge shotgun during the Bogenville campaign, later described the tactical evolution in a 1944 interview with Marine Corps historians. “We learned that in Thick Jungle, the old infantry tactics don’t apply,” he explained. “You can’t see the enemy until you’re practically on top of them.

By the time you identify a target, acquire your sight picture, and squeeze off a carefully aimed rifle shot, you’re probably already hit. But with a scatter gun, you just snap it up and pull the trigger. At 10 ft, you don’t need to aim precisely. You just need to point it in the right general direction, and the spread pattern does the rest.

It’s faster, deadlier, and psychologically, it terrifies the enemy when they realize they can’t even get close enough to use their bayonets. The psychological dimension McKenzie mentioned would prove crucial to the weapon’s effectiveness. The sound of a shotgun blast differs fundamentally from a rifle shot.

Where a rifle produces a sharp crack, a shotgun creates a deep, thunderous boom that seems to shake the air itself. This auditory signature combined with the visible effects of buckshot impacts created immediate psychological impact beyond the weapon’s physical lethality. Japanese soldiers who witnessed a comrade hit by rifle fire might continue fighting depending on the wounds location and severity.

But soldiers who saw a comrade struck by a shotgun blast at close range, who watched the immediate and devastating trauma that multiple pellets inflicted experienced visceral shock that temporarily paralyzed decision-making. American forces exploited this psychological effect deliberately. Marines learned to use shotgun blast to break up Japanese bonsai charges in confined spaces where the charges might otherwise succeed through sheer momentum and numbers.

In cave clearing operations, a single shotgun blast fired into a confined space created acoustic and physical trauma effects that stunned defenders and allowed follow-up forces to enter with reduced risk. The weapon’s sound became associated with particular tactical situations so that Japanese soldiers began to recognize and fear the distinctive boom even before seeing its effects.

None of this tactical evolution appeared in Japanese intelligence assessments reaching frontline units. Teshi Marimoto and his platoon mates prepared for the Bogenville operation with thoroughly outdated assumptions about the threats they would face. They studied maps showing likely American positions, calculated optimal ambush locations, rehearsed coordinated fires using rifles and light machine guns.

They fixed bayonets and practiced their charging techniques, building themselves psychologically for the intimate violence of close combat. They checked ammunition supplies and confirmed they carried sufficient rounds for extended engagements. They prepared for everything except what was actually coming.

The Marines appeared exactly when expected, moving along the trail with tactical spacing that separated them enough to prevent a single burst of fire from hitting multiple targets. Teeshi counted eight men in the patrol, noting their cautious movements and frequent pauses to scan the jungle. Through his rifle sites, he observed their equipment, the familiar olive drab uniforms, the M1 helmets, the various weapons they carried.

Most had rifles or carbines. One man carried what appeared to be a Thompson submachine gun. And at the front of the patrol walking point position, one Marine carried a shorter weapon that Teeshi did not immediately recognize. Lieutenant Watchab’s hand signal indicated they would wait until the patrol center entered the kill zone before initiating contact.

Standard procedure. The Americans continued forward, seemingly unaware of the 38 rifle barrels tracking their movements. Teeshi’s breathing slowed as he focused on his designated target, the second man in line. His finger rested lightly on the trigger. around him. He could hear the subtle sounds of other soldiers making final adjustments to their positions.

The moment stretched out, tense and electric. Then everything happened faster than conscious thought could follow. The point marine, the one with the unfamiliar weapon, suddenly froze. His head turned slightly toward Teeshi’s position. Whether he had seen movement, heard a sound, or simply felt the weight of hostile attention, Teeshi would never know.

But the marine was raising his weapon even as Lieutenant Watonab gave the signal to fire. Teeshi’s finger tightened on his trigger. And in that fraction of a second before his rifle cracked, the marine’s weapon spoke first with a sound unlike anything Teeshi had ever heard in combat. The boom seemed to compress all the air in the jungle into a single explosive pulse.

But it was what happened after the sound that would sear itself into Teeshi’s memory. The marine to his left, Private Ichiro Tanaka, seemed to simply disintegrate from the chest up. There was no wound in the conventional sense, no bullet hole that could be bandaged. Instead, Tanaka appeared to come apart, his torso shredded by multiple impacts in the span of a millisecond.

He collapsed without a sound, killed so quickly, his nervous system had no time to register pain or shock. The entire engagement lasted perhaps 20 seconds, though Teeshi’s memory would compress and expanded into something outside normal time. Japanese rifles cracked in ragged sequence as soldiers fired at the Americans. The Marines scattered with practice deficiency, some dropping into cover, others returning fire immediately.

But the distinctive boom of that unfamiliar weapon continued to punctuate the firefight. And each time it sounded, another Japanese soldier went down with wounds that seemed impossibly severe for a single shot. Teeshi fired his rifle twice before the reality of what he was facing penetrated his tactical training.

The Americans were not retreating. They were not breaking under the ambush as doctrine predicted. And that weapon, that impossible weapon that made thunder and tore men apart, was being used by at least three Marines he could now see. One of them was advancing directly toward the Japanese position, firing and reloading with mechanical efficiency while other Marines provided covering fire.

Lieutenant Watanabe screamed the order to fix bayonets and charge. It was the correct tactical response according to their training. Close the distance, get inside the effective range of those devastating weapons, engage in close combat where Japanese training would prevail. Teeshi rose from his position along with a dozen other soldiers, their bayonets glinting in the filtered jungle light.

The charge covered perhaps 15 ft before two more Marines appeared from concealment, both carrying those thunder weapons. The simultaneous boom of both shotguns firing at pointlank range into the charging soldiers created a slaughter that defied military terminology. Bodies didn’t fall so much as collapse like puppets with severed strings, hit by overlapping patterns of buckshot that inflicted catastrophic trauma across their entire torsos.

Teaeshi threw himself sideways behind a fallen log an instant before Buckshot chewed through the space his chest had occupied. Splinzers exploded from the log as pellets struck its surface, several penetrating the rotting wood to embed themselves in his left arm. The burning pain shocked him less than the realization that formed in his mind with perfect clarity.

Everything they had been taught was wrong. The Americans had weapons that made their defensive doctrine obsolete. His training, his preparation, his spiritual readiness, none of it mattered against a weapon that could kill him before he got close enough to use his bayonet. Lieutenant Watanabe’s voice screamed orders from somewhere to Teeshi’s right, but the words made no sense, calling for tactics that no longer applied to this new reality.

The ambush had reversed itself. Now the Japanese soldiers were pinned down while Marines maneuvered around their flanks with those devastating close-range weapons. Teeshi could hear the distinctive boom approaching from his left, getting closer with each shot. His rifle felt suddenly inadequate in his hands, designed for a kind of warfare that was not happening here.

He had five rounds loaded and perhaps 30 more in ammunition pouches. The Americans seemed to have unlimited ammunition and weapons specifically designed to win this exact type of engagement. The thought that formed in his mind felt like betrayal, but he could not suppress it. They prepared us for the wrong war, and now we are going to die because someone lied about what we would face.

The sound of that shotgun, that impossible thunder weapon, continued to echo through the jungle, punctuated by the screams of his friends, and the desperate crack of Japanese rifles that seemed increasingly feudal against an enemy who had brought exactly the right tools for this particular kind of hell. The survivors of that first encounter stumbled back to their company headquarters 3 hours later, carrying four wounded and leaving 14 dead behind.

Teeshi Morimoto walked in a daysaze, his left arm crudely bandaged where buckshot pellets had penetrated the log he’d hidden behind. The physical wound troubled him far less than the mental confusion that gripped his mind like a vice. Captain Yoshio Nakamura listened to Lieutenant Watanabe’s report with increasing agitation, interrupting frequently to demand clarification about the weapons that had caused such devastation.

Watanab struggled to describe what they had faced. The words felt inadequate. He kept returning to the sound, that distinctive thunderous boom that was nothing like rifle fire or machine gun bursts. He described the wounds, trying to convey the shocking trauma that single shots had inflicted. Captain Nakamura initially suspected exaggeration born from shock and defeat.

Ambushes went wrong sometimes. Perhaps the Americans had been better positioned than anticipated. Perhaps they had carried more automatic weapons than expected. But as more survivors provided consistent accounts, as the medical officer examined the wounded and confirmed that their injuries showed patterns consistent with multiple simultaneous projectile impacts, Nakamura’s skepticism transformed into a deeper unease.

The medical officer, Lieutenant Hideo Matsumoto, had served in China and Malaya before arriving on Bogenville. He had treated thousands of combat casualties and considered himself thoroughly familiar with wound patterns from every weapon in use on modern battlefields. What he observed in the survivors challenged his professional certainty.

Rather than a single penetration, his wound consisted of five separate channels, each approximately 7 mm in diameter, spread across a 20 cm area of his thigh. Two pellets had passed completely through the limb, exiting the back of his leg. Three remained embedded in bone and muscle. Matsumoto extracted one pellet and examined it carefully under lamplight.

It was spherical, approximately 9 mm in diameter, made of lead, not a rifle bullet, not shrapnel from a grenade, something else entirely. Captain Nakamura forwarded an urgent report to regimental headquarters describing the engagement and requesting intelligence assessment of the American weapons involved.

His report included Matsumoto’s medical findings and Lieutenant Watanab’s tactical observations. The response arrived 2 days later and revealed a troubling pattern. Three other companies in the regiment had reported similar encounters over the previous week. Each had faced American forces using short-ranged weapons of devastating effectiveness in close quarters engagements.

Each had suffered disproportionate casualties when attempting to close with bayonets, the standard tactical response to enemy contact at intimate distances. Regimental intelligence officer Major Toshiro Yamamoto compiled these reports into a comprehensive assessment that finally identified the weapon causing such havoc.

The Americans were deploying shotguns, specifically military versions of sporting weapons in frontline combat roles. Yamamoto’s report acknowledged that this represented a significant tactical development that existing Japanese doctrine failed to address. He noted that the weapons appeared most commonly in Marine Corps units and seemed particularly prevalent among soldiers assigned to point positions and assault teams.

His analysis concluded with a recommendation that Japanese troops modify their close combat tactics to account for weapons optimized for ranges between 5 and 20 m. The report reached frontline units during the second week of November, but the recommendations it contained proved far easier to write than to implement. Japanese infantry tactics relied fundamentally on the rifle and bayonet combination.

Training emphasized marksmanship at medium ranges and aggressive close combat when enemies reached intimate distances. The tactical manual contained no procedures for engaging an enemy who possessed weapons that dominated the intermediate zone between rifle effectiveness and bayonet range. Soldiers like Teeshi found themselves in a doctrinal void.

Their training suddenly inadequate for the combat environment they faced daily. Lieutenant Watsanabe gathered his remaining platoon members to discuss the new intelligence assessment and considered tactical modifications. The discussion revealed the depth of the challenge. Private First Class Masaru Kobayashi suggested maintaining greater distance during engagements, using cover to keep the Americans beyond effective shotgun range.

But the jungle terrain made this nearly impossible. Visibility rarely exceeded 15 meters and often dropped to 5 meters or less in dense vegetation. Maintaining standoff distance meant abandoning the ambush tactics that represented their primary defensive method. Corporal Hiroshi Tanaka proposed targeting the Marines carrying shotguns first, eliminating the weapons before closing to bayonet range.

This seemed tactically sound until Teeshi pointed out the practical difficulties. The shotgun ararmed marines typically walked point position, meaning they would be first to detect any ambush and first to return fire. Attempting to engage them specifically meant exposing one’s position immediately, losing the element of surprise that made ambushes effective.

Moreover, in the heat of combat at close range, identifying which Americans carried shotguns versus rifles required time and attention that most soldiers lacked while under fire. The conversation continued for over an hour without reaching satisfactory conclusions. Each proposed modification to their tactics created new vulnerabilities or required abandoning advantages.

The fundamental problem remained unsolved. Japanese infantry doctrine assumed rough parody in close quarters weapons with victory determined by training, disciplined, and fighting spirit. The American shotguns had destroyed that assumption by introducing a weapon that simply outmatched Japanese capabilities at the ranges where most jungle combat occurred.

No amount of spiritual preparation could overcome the physical reality that a marine could fire his weapon and hit effectively in the time it took a Japanese soldier to close from 10 m to bayonet range. Word of the shotgun threat spread through Japanese positions on Buganville with remarkable speed transmitted through informal networks that moved faster than official channels.

Soldiers shared stories, each account growing slightly in the telling until the weapons acquired almost mythical characteristics. Some claimed the shotguns could kill at 50 m. Others insisted the weapons fired explosive projectiles that detonated on impact. A few swore the Americans loaded them with poisoned pellets that caused agonizing death from even minor wounds.

These exaggerations reflected the psychological impact of facing a weapon that existing doctrine could not counter effectively. Private Kenji Watanabe, who shared a surname with his platoon leader, but no family relation, kept a diary that survived the war and was later donated to the Yasukuni War Memorial Museum.

His entries from mid- November captured the deteriorating confidence that gripped Japanese infantry. We no longer move through the jungle with the certainty of warriors, he wrote on November 18th. We move like prey animals, flinching at sounds, avoiding contact, knowing that if we encounter the Americans at close range, we face weapons designed specifically to kill us in that circumstance.

Our training taught us to close with the enemy, to rely on our bayonets and fighting spirit when battle became intimate. Now closing with the enemy means walking into the effective range of their thunder weapons. We have become afraid of the very combat distances our doctrine tells us to seek. This psychological erosion manifested in measurable tactical changes.

Japanese ambushes became less aggressive with units initiating contact at longer ranges where shotguns provided no advantage. But this modification forced Japanese soldiers to engage at distances where American rifle accuracy and superior ammunition supplies gave them decisive advantages. Units that maintained traditional close-range ambush tactics suffered devastating casualties when they encountered shotgun ararmed marines.

Units that shifted to longer range engagements found themselves outgunned by American firepower and unable to inflict sufficient casualties to offset their own losses. The Americans recognized these tactical adaptations and responded with refinements of their own. Marine patrols began using shotgun armed pointmen in conjunction with rifle equipped support elements positioned to exploit the longer ranges where Japanese forces now preferred to engage.

When Japanese positions initiated contact at 70 or 80 m, American riflemen would return suppressive fire while shotgun armed marines maneuvered to close the distance. The Japanese then faced an impossible choice between maintaining their positions and being overrun by close assault specialists or withdrawing and exposing themselves to concentrated rifle fire during their retreat.

Teaeshi experienced this tactical evolution firsthand during a patrol on November 23rd. His squad had moved into a position overlooking a trail junction, planning to ambush any American forces that passed through. When a Marine patrol appeared, squad leader Sergeant Ichiro Yamada ordered his men to hold fire until the Americans reached 70 m distance, well beyond effective shotgun range.

The Japanese opened fire with a disciplined volley that dropped two Marines and sent the others diving for cover. standard engagement. But within seconds, American return fire intensified to a level that shocked the Japanese defenders. Rifles cracked continuously from multiple positions, forcing the Japanese to keep their heads down while half the Marine squad maneuvered along the flanks.

Teshi caught glimpses of Marines moving through the jungle with practiced efficiency. Some carrying rifles and providing covering fire, others advancing with those distinctive short weapons held ready. The tactical coordination impressed and terrified him equally. When the shotgun armed Marines closed to within 20 m, the character of the engagement transformed completely.

The thunderous booms began, each accompanied by screams from Japanese positions as Buckshot found targets. Sergeant Yamada attempted to organize a fighting withdrawal, but the Marines pressed their advance aggressively, using grenades to suppress positions and shotgun blasts to clear any resistance they encountered at close range.

The squad lost four men killed and three wounded during the withdrawal. Teeshi escaped with minor shrapnel wounds from a grenade burst, but carried away something more lasting than physical damage. He had witnessed tactical competence that matched or exceeded anything in Japanese doctrine combined with weapons optimized for the actual combat conditions rather than theoretical engagement scenarios.

The Americans were not simply better equipped. They were applying sophisticated combined arms tactics that integrated different weapon systems based on their specific capabilities. They had studied the jungle combat environment and adapted their methods accordingly. The Japanese, meanwhile, were attempting to apply rigid doctrine developed for different terrain and different enemies, making only superficial modifications when reality contradicted their planning assumptions.

By early December, the cumulative effect of these engagements had created a crisis of confidence among Japanese infantry on Bogenville. Casualties mounted steadily as units struggled to develop effective responses to American tactics. Medical facilities reported increasing numbers of soldiers suffering from combat stress disorders, unable to function effectively after repeated exposure to close quarters engagements with shotgun armed opponents.

The psychological trauma of watching comrades torn apart by weapons that inflicted massive immediate damage proved more debilitating than gradually accumulating casualties from rifle fire or artillery bombardment. Lieutenant Colonel Fumio Hayashi, commander of the third battalion, 53rd Infantry Regiment, recognized that his unit faced potential collapse if morale continued deteriorating.

He requested permission from regimental headquarters to withdraw from aggressive patrolling and adopt a more defensive posture, conserving his forces until reinforcements or resupply could reach the island. His request was denied with instructions to maintain pressure on American forces and prevent them from consolidating their positions.

The high command’s response reflected a fundamental disconnect between senior leadership and frontline realities, a gap that would characterize much of the Japanese Pacific war experience. Hayashi faced an impossible situation. His orders demanded aggressive action. His troops were increasingly unwilling to conduct close-range operations against an enemy who dominated those engagements.

His tactical options had narrowed to choices between bad and worse. He could push his men into combat they feared and likely watch his battalion’s effectiveness disintegrate. He could refuse orders and face military justice while his troops faced potential annihilation anyway under a replacement commander.

Or he could find some way to restore his units confidence despite lacking the resources or tactical solutions to address the underlying problem. He chose a middle path that would prove characteristic of Japanese military adaptation throughout the Pacific campaign. Unable to match American material advantages, he emphasized spiritual factors and tactical modifications within existing resource constraints.

He organized intensive night training, reasoning that darkness negated some shotgun advantages by reducing target acquisition speed. He stressed aggressive grenade use at intermediate ranges, attempting to create firepower effects that could compete with American weapons. He personally addressed his troops about Japanese warrior traditions, framing their struggle as a test of character rather than a tactical mismatch.

These measures provided some temporary psychological benefit, but failed to address the fundamental problem. Japanese soldiers remained outgunned at the engagement ranges where most combat occurred. The shotgun’s effectiveness derived from physics and engineering, not from American spiritual superiority or Japanese moral failure.

No amount of exhertation could change the reality that buckshot spreads in a cone pattern that makes hitting easier, that multiple simultaneous projectile impacts inflict more immediate trauma than single bullets, that the weapon’s shocking power disrupted enemy action in ways that rifle fire could not replicate. The grinding combat on Bogenville continued through December and into early 1944 with Japanese forces slowly compressed into increasingly untenable positions.

The shotgun became one element among many in the American tactical system that gradually overwhelmed Japanese defenses. But its psychological impact exceeded its tactical contribution. In the memories of survivors like Teeshi Morimoto, the weapon came to symbolize a larger truth. they had been forced to accept through bitter experience.

Their training had prepared them for an idealized war that existed primarily in doctrine manuals and instructor lectures. The actual war, the one being fought in Bogenville’s jungles, rewarded adaptation, practical thinking, and the willingness to match weapons to tactical requirements rather than forcing tactics to accommodate available weapons.

Teeshi survived the Bogenville campaign, evacuated with dysentery and malnutrition in February 1944 after spending four months in conditions that ground down the strongest soldiers. He carried with him physical scars from multiple minor wounds and deeper psychological marks from repeated exposure to combat that contradicted everything his training had promised.

The sound of that shotgun blast never entirely faded from his memory, appearing in dreams and triggered by unexpected loud noises for decades after the war. In quiet moments, he would remember Private Ichiro Tanaka disintegrating under that first devastating impact and wonder how many deaths might have been prevented if someone in the Japanese military hierarchy had bothered to understand what weapons their enemies actually carried and how they intended to use them.

Up next, you’ve got two more standout stories right on your screen. If this one hit the mark, you won’t want to pass these up.

News

They Mocked His “Backwards” Loading Method — Until His Sherman Destroyed 4 Panzers in 6 Minutes D

At 11:23 a.m. on September 19th, 1944, Private First Class Walter Kowalsski crouched inside his M4 Sherman tank near…

The Most Insane Helicopter Pilot of Vietnam – Ace Cozzalio D

Oh, good girl. You want to hear the story about the deadliest IHOP employee to have ever existed? Yeah….

Why American Soldiers Started Killing Their Own Officers in Vietnam D

Today’s video is brought to you by the good people over at AG1. I told myself I wasn’t doing…

How Canadians Stood Up for Black GIs After U.S. MPs Crossed the Line D

July 1944, Aldershot, England. The summer air hung thick and warm inside the Red Lion Pub. Canadian soldiers sat…

The Ugly Gun That Beat the Beautiful Thompson: M3 Grease Gun’s WWII Revolution D

October 1942, a General Motors Inland Division in Dayton, Ohio, George Hyde, a 52-year-old immigrant from Germany, was completely…

Why U.S. Marines Waited for Japan’s “Decisive” Charge — And Annihilated 2,500 Troops D

July 25th, 1944. Western Guam, Our Peninsula. A narrow strip of land barely half a mile wide, shielding the…

End of content

No more pages to load