October 15th, 1944. The Voj mountains of eastern France stood wrapped in morning fog so thick that Lieutenant James Morrison could barely see his own hand extended before him. His platoon, part of the American forces pushing through the heavily forested terrain, had been moving cautiously for 3 days through what the locals called the most unforgiving landscape in all of France.

Morrison believed they were closing in on a lightly defended position he believed wrong. Before we dive into this story, make sure to subscribe to the channel and tell me in the comments where you’re watching from. It really helps support the channel. What Morrison and his men were about to discover would challenge everything they understood about psychological warfare.

And one soldier’s ingenuity would transform a desperate situation into one of the most remarkable tactical victories of the European campaign. The platoon consisted of 42 men exhausted from weeks of continuous advancement through territories that had been occupied for 4 years. Among them was Private First Class Thomas Beay, a Navajo man from the vast desert lands of Arizona who had grown up speaking Da Bizard as his first language.

At 23 years old, Beay had been in Europe for 6 months serving as a radio operator and occasional scout. His commander, Latutenant Morrison, was a 31-year-old former teacher from Pennsylvania, who had learned to trust Beaye’s instincts about terrain and movement. The fog began to lift around 8:00 in the morning, revealing what Morrison had feared most.

They weren’t approaching a lightly defended position. Instead, spread across the forested hillside ahead, dug into positions that had been prepared with meticulous care, were elements of a German defensive line that appeared to contain at least 50 soldiers, possibly more. The Americans were outnumbered, outgunned, and completely exposed on the slope below.

Sergeant William Chen, a Chinese American from San Francisco who had fought his way from North Africa through Sicily and into France, crouched beside Morrison as they assessed the situation. Chen had seen enough combat to know when a position was untenable. His voice was barely a whisper as he spoke. “Lieutenant, we need to fall back,” Chen said, his eyes scanning the treeine where muzzle flashes would soon appear.

“We’re in a shooting gallery here.” Morrison knew Chen was right, but retreat across the open slope would be suicide. The German positions commanded the high ground with clear fields of fire. Any movement would trigger an immediate response. They were trapped, and the Germans knew it. Private First Class Robert Kowalsski, a factory worker’s son from Detroit, who had joined the army on his 18th birthday, lay flat against the cold earth beside his squadmates.

He had been writing letters home about how the war would be over by Christmas. Now watching the German positions through the dissipating fog, he wondered if he would ever mail those letters. His fingers trembled as he checked his rifle, a motion he had performed thousands of times, but which now felt entirely inadequate.

From the German positions, Hedfeld Wel an Vber surveyed the American platoon through his binoculars. At 38 years old, Veber had fought in Poland, France during the earlier campaign and spent two brutal winters on the Eastern Front before being reassigned west. He commanded approximately 52 men, including veterans who had survived campaigns that had broken lesser soldiers.

They held a position that military doctrine would call nearly impregnable. The Americans below were completely at their mercy. Veber turned to Gerright Hans Becka, a 19-year-old from Bavaria, who had been conscripted only 7 months earlier, but had learned quickly how to survive. Becker’s hands were steady on his weapon.

But his eyes showed the weariness that came from knowing that even in victory, there would be casualties. “They have nowhere to go,” Veber said to Becker in German, his voice carrying the flat certainty of experience. “We wait for them to make the first move, then we finish this quickly.” The standoff lasted for what felt like hours, but was actually only minutes.

Morrison knew that waiting only gave the Germans time to call for reinforcements. His mind raced through options, each one ending in catastrophe. A frontal assault would be cut down before they advanced 20 m. Retreat meant certain casualties. Surrender would mean prisoner of war camps, and Morrison had heard enough stories to know that was a fate to be avoided, if possible.

It was Private Beay who broke the silence, moving carefully to Morrison’s position. His face showed none of the fear that Kowalsski and others displayed. Instead, there was a thoughtfulness in his expression, as if he were solving a complex puzzle. “Lieutenant, I have an idea,” Beay said, his English carrying the slight accent that marked him as someone for whom it was a second language.

“It’s unconventional, but it might work.” Morrison looked at him, desperate enough to consider anything. The morning sun was burning off the last of the fog and soon they would be completely visible to the German positions. Time was running out. Talk, Morrison said. Beay explained his plan in quick, efficient sentences.

Morrison’s first reaction was disbelief. His second was to recognize that they had no better options. The plan relied entirely on psychological effect, on creating an illusion of strength where only vulnerability existed. It was audacious, possibly insane, and their only chance. “Do it,” Morrison said. “We’ve got nothing to lose.

” Be gay moved to a position where his voice would carry up the slope toward the German lines. He took a deep breath, thinking of his grandfather and the stories of warriors who had defended their lands against overwhelming odds. Then he began. The sound that emerged from Beay’s throat was like nothing the Germans had ever heard in this war.

It was a traditional Navajo war cry, a vocalization that had echoed across desert canyons for generations, modified and amplified with all the power his lungs could provide. The cry started low and built in intensity, a ulating call that seemed to come from multiple directions at once, as it bounced off the trees and rocks of the mountainside.

The sound rose and fell in patterns that seemed almost supernatural in their complexity. Be gay had learned these calls from his uncle who had learned them from his father stretching back through generations of warriors. But Beay added his own innovation, varying his position every few seconds, moving behind trees and rocks to create the acoustic illusion that the sound was coming from multiple sources.

Then without warning, he switched tactics. Using techniques he had developed as a child, calling across vast distances in the Arizona desert, beay began producing different vocal patterns, each cry seemed to come from a different direction, some higher up the slope, others to the flanks. The natural acoustics of the forested terrain amplified and distorted the sounds, creating an audio landscape that suggested not one man but many.

In the German positions, the effect was immediate and profound. Becca’s head snapped toward the sound, his eyes wide with confusion. The cries seemed to be coming from everywhere at once, suggesting that the small American platoon they had observed was merely the forward element of a much larger force. Veber felt the first stirrings of doubt.

He had fought across half of Europe and had heard every type of combat sound imaginable, but these vocalizations were entirely outside his experience. They seem to suggest indigenous troops, possibly American forces augmented by colonial soldiers or specialized units he had not encountered before. More importantly, the way the sounds echoed and overlapped suggested numbers, movement, encirclement.

“How many are there?” Becker asked, his voice tight with tension. Weber didn’t answer because he didn’t know. The acoustic confusion made it impossible to determine how many men were producing the sounds. His tactical training told him that forces attempting encirclement would use signals to coordinate their movements.

These strange cries could be exactly that, communication in a language he couldn’t understand, coordinating a trap. Beay continued his performance, now adding variations that simulated the sounds of men moving through brush, of equipment being positioned, of a large force maneuvering for an assault. He used his knowledge of how sound traveled through forest terrain, intentionally creating echoes and reverberations that suggested dozens of men where there was only one.

Morrison watched in amazement as the German positions began to show signs of confusion. Heads appeared above entrenchments, looking not toward the exposed American platoon, but into the forest flanks and rear, searching for the source of these otherworldly sounds. The psychological advantage had shifted in a matter of minutes.

Sergeant Chen recognized what was happening and acted without needing orders. He began moving his squad in a pattern that suggested larger numbers, appearing briefly in one position, then quickly relocating to appear elsewhere. Kowalsski, despite his fear, understood the game and played his part, showing himself at intervals that suggested multiple squads maneuvering simultaneously.

The German interpretation of events was cascading toward panic. Weber had seen encirclements before, had been caught in one during a winter retreat two years earlier that had cost his unit 70% casualties. The memory of that nightmare was visceral and immediate. These sounds, this apparent movement on the flanks and rear, matched the pattern of forces that had surrounded his previous unit.

“We’re being encircled,” a young German soldier called out, his voice cracking with stress. Weber made the calculation that commanders have made throughout history when facing uncertain odds. He had 52 men in positions that were strong for frontal defense, but vulnerable to attacks from multiple directions. If the sounds indicated what he suspected, if a larger American force was indeed moving to surround them, then staying in position meant potential capture or annihilation.

The prudent choice, the survivable choice was to withdraw while they still had an escape route. “Prepare to fall back,” Weber ordered, his voice carrying the authority that came from years of command, controlled withdrawal to the secondary positions. The German soldiers, many of whom had been thinking the same thing, needed no further encouragement.

The withdrawal began with the discipline of experienced troops, but there was an undercurrent of urgency that suggested how thoroughly the psychological attack had worked. They moved quickly through the forest, abandoning positions that had taken days to prepare, driven by sounds that suggested an enemy force many times larger than the 42 Americans actually present.

Beay maintained his vocal assault for another 5 minutes, varying the sounds and directions until he was certain the German withdrawal was complete. Then, as suddenly as it had begun, the forest fell silent. Morrison rose slowly from his position, hardly believing what he had just witnessed, where minutes before had been an impregnable defensive line, there were now only abandoned entrenchments.

His 42 men, who had been moments from potential catastrophe, now held the high ground without having sustained a single casualty. Chen approached the German positions cautiously, confirming they were indeed abandoned. He turned back to Morrison with an expression that mixed relief with disbelief.

They left everything, Chen said, gesturing to the abandoned supplies and equipment. They were in full retreat mode. Kowalsski and the other men began to emerge from their positions, the realization of their impossible salvation slowly dawning on them. They had been saved not by superior firepower or tactical brilliance, but by one man’s ingenuity and the power of acoustic psychology.

Morrison found Beay sitting against a tree, catching his breath after his extraordinary performance. The private’s throat was raw from the sustained vocalizations, but his expression showed quiet satisfaction. That was the most incredible thing I’ve ever witnessed,” Morrison said, sitting down beside him.

“Where did you learn to do that?” Beay smiled slightly, thinking of the red rock country of his homeland. He explained how sound traveled differently in the desert than in forests, how his people had developed methods of communication across vast distances, how the war cries of his ancestors had been designed not just to intimidate but to confuse and disorient.

He had adapted ancient knowledge to modern warfare using acoustic principles his people had understood for generations. My grandfather always said that the smartest warrior is the one who wins without creating more widows. Big A said, his voice but steady. Today we did that. The tactical importance of what had occurred became clear in the following hours.

The position the Germans had abandoned was a key point in their defensive line. Its capture achieved without the expected casualties allowed American forces to advance through a sector that intelligence had predicted would cost dozens of lives to secure. The ripple effects of that one morning’s acoustic deception would influence the campaign for weeks to come.

Word of the incident spread through the American units in the region, though the story became increasingly embellished with each retelling. Some versions claimed Beay had single-handedly driven off a 100 German soldiers. Others suggested he had used supernatural powers. The truth was remarkable enough without embellishment, but Morrison understood why the story had captured the imagination of troops who too often faced overwhelming odds.

For the German forces who had retreated, the experience remained a source of confusion and embarrassment. Veber filed a report describing the encounter, honestly, noting that they had withdrawn in the face of what appeared to be a larger force attempting encirclement. His superiors, lacking any understanding of Navajo vocalizations or acoustic psychology, accepted the report at face value.

The incident became a footnote in German tactical assessments, one more example of American forces employing unexpected tactics. Becker, the young German soldier, would survive the war and later immigrate to America in 1952. when he eventually learned the truth about what had happened that October morning, that the sounds that had driven [clears throat] his unit into retreat had come from a single Navajo soldier, using traditional vocalizations, his reaction was one of professional respect.

He had been part of military forces that prided themselves on discipline and tactical sophistication, yet they had been completely outmaneuvered by knowledge far older than modern warfare. The broader implications of Beay’s improvisation were not lost on military intelligence. While the famous Navajo code talkers had been using their language for secure radio communications in the Pacific theater, Beay had demonstrated another application of indigenous knowledge to modern warfare.

His use of traditional war cries and acoustic techniques showed how ancient wisdom could complement contemporary military technology. Morrison submitted beay for recognition though the nature of the achievement made it difficult to categorize in traditional military terms. How does one write a commendation for psychological warfare conducted entirely through vocal performance? The citation eventually filed described exceptional initiative and courage in the face of superior enemy forces which was accurate but barely captured the creativity and

cultural knowledge that had made the moment possible. For Private Beay himself, the incident was both validating and bittersweet. He had grown up in a country that had systematically attempted to erase his language and culture. He had attended boarding schools where speaking Navajo was punished, where he and other indigenous children were told their heritage was primitive and worthless.

Yet here in the forests of France, that same supposedly primitive culture had provided the knowledge that saved 42 American lives and achieved a tactical objective deemed impossible by conventional military wisdom. The war continued for another 7 months after that October morning. Beay participated in the push across the Rine and into Germany proper, serving with distinction throughout.

He survived the war and returned to Arizona in 1946 where he lived quietly, rarely speaking of his experiences. The dramatic morning in the Voj mountains became one of many stories he kept to himself, sharing them only with family and close friends. Lieutenant Morrison returned to Pennsylvania and resumed teaching. But he never forgot the lesson Beay had taught him about the diverse forms intelligence can take.

In his classroom, he made a point of emphasizing that solutions to problems often come from unexpected sources, that cultural knowledge represents a form of expertise as valuable as any technical training. He stayed in touch with Beay through occasional letters. Gay friendship formed in moments of crisis that transcended the differences in their backgrounds.

Sergeant Chen returned to San Francisco and opened a small restaurant where he became known for telling stories of the war to anyone who would listen. His favorite story was always about the morning when a single voice drove away 52 well-entrenched soldiers, a tale he told with growing appreciation for its improbability each time he recounted it.

Kowalsski went back to Detroit and took a job in the same factory where his father had worked. He married his childhood sweetheart and raised four children to whom he told modified versions of his war experiences. But he always emphasized the story of Beay and the war cry using it to teach his children that courage came in many forms and that the most powerful weapons were sometimes the ones you couldn’t see or touch.

The historical record of that day exists primarily in unit reports and personal memoirs. Morrison’s afteraction report filed with typical military brevity noted the capture of a strategic position with zero casualties through unconventional tactical methods. The German report from Weber’s unit described withdrawing from a position under apparent threat of encirclement by a numerically superior force.

Neither document captured the extraordinary nature of what actually occurred. Decades later, military historians studying the campaign would occasionally encounter references to the incident and puzzle over the discrepancy between German force strength and the American unit that displaced them. Without understanding the acoustic deception involved, the engagement appeared anomalous, one of those statistical oddities that appear in every war.

Only those who were present understood the full story, and many of them never spoke of it in detail. The incident in the Voge Mountains represents something profound about the nature of warfare and human ingenuity. Throughout history, military forces have sought advantages through technology, training, and numerical superiority.

Yet time and again, individual creativity and cultural knowledge have proven capable of overcoming conventional advantages. Beay’s improvisation that October morning was not the result of military training or technological innovation. It was the application of traditional knowledge passed down through generations adapted brilliantly to an immediate crisis.

This story also illuminates the complex relationship between American society and its indigenous populations during the 1940s. The same government that had attempted to suppress Native American languages and cultures for generations was simultaneously benefiting from the unique capabilities those cultures provided.

Navajo code talkers in the Pacific were creating an unbreakable code using a language that American schools had tried to eliminate. Beay in Europe was using traditional vocalizations to achieve tactical objectives. The irony was not lost on the Native Americans who served. The psychological aspects of the encounter reveal fundamental truths about human perception and decision-making under stress.

Vber was an experienced commander who had survived years of combat through sound judgment. Yet, when faced with acoustic information that suggested a threat pattern he recognized, his rational response was to withdraw. The human brain is wired to recognize patterns and respond to perceived dangers. And Big A had understood this at an intuitive level.

He created not just sound, but a narrative of threat that Vber’s experience interpreted as genuine. The 42 American soldiers who witnessed that morning carried the memory for the rest of their lives. For many, it became a defining moment, proof that human creativity and courage could overcome seemingly impossible odds in reunions and correspondence over subsequent decades.

They would return to that story, marveling at how close they had come to disaster, and how one man’s initiative had transformed their fate. The broader lesson extends beyond military history into the realm of cultural preservation and respect. Beay’s ability to save those lives came directly from knowledge that American educational and social policies had attempted to erase.

His grandfather’s teachings about war cries and acoustic communication passed down through oral tradition across generations proved more tactically valuable in that moment than any weapon or technology the American military had developed. It stands as a powerful argument for the preservation of traditional knowledge and cultural diversity.

For the German soldiers who retreated that day, the experience became one of those war stories that seemed almost impossible to believe. Many of them in postwar years struggled to explain to themselves how they had abandoned such a strong position. Without the context to understand what had actually happened, they were left with only the memory of sounds that had seemed to promise encirclement and potential catastrophe.

Some carried a sense of shame about the withdrawal, not understanding that they had been the targets of psychological warfare so innovative that no military doctrine of the time addressed it. The tactical success achieved that morning had strategic implications that extended well beyond the immediate capture of that position.

The German defensive line in that sector had been anchored on the positions Veber’s unit had occupied. Their withdrawal created a gap that American forces exploited over the following days, leading to a broader collapse of German positions in the region. A single morning’s acoustic deception contributed to operational successes that affected thousands of soldiers and accelerated the Allied advance by days or possibly weeks.

What makes this story particularly powerful is its illustration of how individual agency can influence large-scale events. Military history tends to focus on generals, major battles, and strategic decisions made at high levels. Yet, here was a private, a man at the lowest level of military hierarchy whose quick thinking and cultural knowledge altered the course of a campaign.

It reminds us that history is shaped not just by leaders, but by countless individual decisions made by people whose names rarely appear in history books. The story of Thomas Beay and the war cry that routed 52 German soldiers is ultimately about the value of diversity in all its forms. It’s about how different cultural backgrounds, languages, and traditions represent not just heritage to be preserved, but practical knowledge that can be applied to solving contemporary problems.

It’s about how the most effective solutions sometimes come from the most unexpected sources, and how prejudice and cultural erasure represent not just moral failures, but practical losses of potentially valuable knowledge. In the vast tapestry of World War II stories, most focus on massive battles, technological breakthroughs, or strategic decisions that affected millions.

This story operates on a different scale, but is no less significant. It shows how one person, drawing on ancestral knowledge and personal courage could transform a desperate situation into a victory that saved lives and influenced the broader campaign. It reminds us that history is made not just by the famous and powerful, but by individuals who in moments of crisis draw on every resource available to them, including those that others might dismiss as irrelevant or outdated.

Thomas Beay returned to the Navajo Nation after the war and lived into his 80s, passing away in 2004. At his funeral, elderly veterans from his old unit traveled to Arizona to pay their respects. men who credited him with saving their lives on that foggy October morning. They shared stories with his grandchildren, ensuring that the tale of the war cry would be passed down through another generation, part of a continuing oral tradition that had made the moment possible in the first place. And that concludes our story.

If you made it this far, please share your thoughts in the comments. What part of this historical account surprised you most? Don’t forget to subscribe for more untold stories from World War II and check out the video on screen for another incredible tale from history.

News

Why the Viet Cong Feared the SAS More Than Any American Unit

Fuaktui Province, South Vietnam, March 17th, 1966. The Vietkong sentry never heard them coming. Nuan Vanam had survived 2…

They Mocked His “Backwards” Loading Method — Until His Sherman Destroyed 4 Panzers in 6 Minutes D

At 11:23 a.m. on September 19th, 1944, Private First Class Walter Kowalsski crouched inside his M4 Sherman tank near…

The Most Insane Helicopter Pilot of Vietnam – Ace Cozzalio D

Oh, good girl. You want to hear the story about the deadliest IHOP employee to have ever existed? Yeah….

Why American Soldiers Started Killing Their Own Officers in Vietnam D

Today’s video is brought to you by the good people over at AG1. I told myself I wasn’t doing…

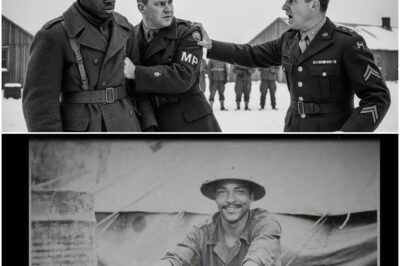

How Canadians Stood Up for Black GIs After U.S. MPs Crossed the Line D

July 1944, Aldershot, England. The summer air hung thick and warm inside the Red Lion Pub. Canadian soldiers sat…

The Ugly Gun That Beat the Beautiful Thompson: M3 Grease Gun’s WWII Revolution D

October 1942, a General Motors Inland Division in Dayton, Ohio, George Hyde, a 52-year-old immigrant from Germany, was completely…

End of content

No more pages to load