the bomber that tried to become a fighter and failed brilliantly. At 11:47 a.m. on May 29th, 1943, [music] Captain James Hartwell climbed into the cockpit of his B17 at RAF Alenberry. He was 26 years old with 42 combat missions behind him, [music] more than most crews would ever fly.

But what he was about to take into [music] the sky that day, no one in the Eighth Air Force had ever tried before. The aircraft sitting on the tarmac looked like a flying fortress. Same four engines, [music] same wings, same tail. But it wasn’t. It was 4,000 [music] lb heavier, bristling with more guns than anything the sky had ever seen.

1650 caliber machine guns pointing in [music] every direction, ready to tear apart anything that came close. They called it the YB40, the Flying Destroyer. A bomber built to protect bombers. On paper, it was genius. By summer’s end, it would be called something else entirely, a catastrophic [music] failure. But here’s the thing about failures.

Sometimes they teach us more [music] than victories ever could. To understand why the YB40 was even built, you need to understand [music] what was happening in the skies over Europe in early 1943. The Eighth Air Force was dying. Not slowly, not quietly. They were being slaughtered. Every mission into Germany was a death sentence.

B7 crews climbed into their aircraft knowing the odds. Half of them wouldn’t [music] make it to 25 missions. That was the magic number. 25 missions and you could go home. But most men never saw it. They died over Hamburg, over Schweinford, over Bremen, torn apart by [music] flack and fighters before they ever reached the target.

And the worst part, command knew exactly why. The P-47 Thunderbolts and P-51 Mustangs, the fighters that were supposed to protect the bombers, [music] didn’t have the range. They could escort the formations to the French coast. maybe a hundred miles into Germany if they were lucky. But then they had to turn back.

Fuel tanks empty, bombers on their own. And that’s when the Luftvafa struck. German fighter tactics were brutally effective. Messer Schmidt 109’s [music] and Faka Wolf 190s didn’t waste time with fancy dog fighting. They came [music] in fast. They came in hard. And they came from 12:00 high, straight ahead, nose to [music] nose, where the B17’s defensive guns couldn’t track them.

The bombers’s waist gunners useless. The tail gunner, wrong direction entirely. The top turret gunner could swing around, but by the time he did, the German was already passed. [music] Having pumped 20 mm cannon shells straight through the cockpit. Entire formations were torn apart. On one mission to Regensburg in August 1943, [music] the 8th Air Force lost 60 bombers in a single day. 600 men gone.

Just like that. The desperate [music] solution. Headquarters was desperate. They needed a solution and they needed it fast. The strategic bombing campaign, [music] the entire plan to Nazi Germany’s war machine, was on the verge of collapse. If they couldn’t [music] protect the bombers, they couldn’t bomb the factories.

And if they couldn’t bomb the factories, the war in Europe would [music] drag on for years. Fighter escorts were still 2 years away from having the range they needed. So, someone at [music] rightfield in Ohio had an idea, a radical idea, a crazy idea. If fighters can’t escort [music] the bombers all the way to the target, what if we turn a bomber into a fighter? Not a replacement, [music] an escort, a gunship, a flying fortress that could stay with the formation the entire mission, absorbing attacks, shooting down German [music] fighters,

and giving the bombladen B7s a chance to reach the target and get home alive. [music] They called it the YB40 program. And on [music] paper, it looked like it just might work. In February 1943, Douglas aircraft received an urgent contract. Take a standard B17 flying fortress [music] and turn it into the most heavily armed bomber in the world.

No bombs, no bombader, just guns. Lots of guns. Engineers went to work. They ripped out the Bombay entirely and turned it into a massive ammunition storage bunker. 11,000 [music] rounds of 50 caliber ammunition, enough to fight for hours without reloading. They added a brand new twin 50 caliber chin turret directly under the nose, specifically designed [music] to counter those deadly frontal attacks.

Behind the cockpit, they installed a second dorsal turret right behind the radio room, giving overlapping fields of fire. The waist guns [music] were doubled, four guns instead of two. Extra cheek guns were mounted in the nose windows, and the [music] tail turret was completely redesigned with the new Cheyenne model, offering better visibility and more protection for the tail gunner.

Then came the armor. steel plating around the gunner’s positions, reinforced bulkheads, thicker glass in the turrets. [music] They weren’t just building a bomber, they were building a flying tank. The result, 4,000 lb heavier than a [music] standard B7, but with 1650 caliber machine guns and enough ammunition to fight off an entire Luftvafa squadron, it looked absolutely unstoppable.

Douglas built 12 [music] YB40s and shipped them to England in April. The 92nd Bomb Group received them at RAF Alenberry, [music] and the crews who saw them for the first time just stood there staring. Gunners ran their hands over [music] the chin turret, grinning. Pilots whistled low. This thing was a [music] monster.

Captain James Hartwell’s crew drew aircraft number 425738. [music] They named it Hedgehog. May 29th, [music] 1943. The briefing room at Alcenberry was packed. Cigarette smoke hung thick in the air. Maps covered the wall. Blue lines marking the route. Red circles marking flack zones. The target, San Nazair, France. The submarine pens.

Reinforced concrete bunkers were German Ubot refueled and rearmed before heading back into the Atlantic [music] to sink Allied convoys. The mission commander laid it out. 168 B17s [music] would hit the pens. The YB40s, four of them including Hartwell’s Hedgehog, would fly alongside the formation, positioned to intercept German fighters before they could reach the bombers.

The briefing officer called it a historic test, and Hartwell called it something else entirely. He leaned over to his co-pilot, [music] Lieutenant Frank Benson, and whispered, “Let’s hope this thing flies better than it looks heavy.” Benson didn’t laugh. At 1:50 p.m., the engines roared to life. One by one, the bombers taxied [music] to the runway.

Hartwell pushed the throttles forward and Hedgehog began to roll slowly. Too slowly. The extra weight made every movement sluggish. The tail lifted late. The wheels clung to the runway longer than usual. And when [music] they finally lifted off, the climb rate was pitiful. A standard B7 could reach 20,000 ft bombing altitude in about 25 minutes.

Hedgehog took 48, nearly twice as long. Hartwell felt it in the controls. The yoke was heavy. The aircraft wanted to wallow, not climb. Every adjustment took more effort, more muscle, and the engines were already running hot. But they made it. By 3:30 p.m., the formation was assembled over the English Channel, and the YB40 had taken its position on the edge of [music] the group, the most exposed position where German fighters would hit first. Hartwell keyed the intercom.

All gunners, check your weapons. Stay sharp. This is what we train for. In the chin turret, Sergeant Eddie Clark loaded the first belt of ammunition and chambered a round. Ready down here, Captain. Let’s see what this thing can do. At 4:02 p.m., the formation crossed the French coast.

Below them, the cliffs of Britany stretched out, [music] gray and jagged. And then the flack started. Black puffs of [music] smoke erupted around them. 88 mm shells bursting at altitude, each one capable of shredding a bomber to pieces. The formation tightened up. Radio chatter picked up. Bandits 11:00 [music] high. I count six, no, eight contacts.

Faka Wolf’s coming in fast. Hartwell saw them. Six silver specks [music] diving out of the sun, growing larger every second. Faka Wolf 190s, fast, deadly, and flown by some of the best pilots the Luftvafa had. They were coming in from behind, trying to pick off the tail end bombers.

Tail gunner, you see them? Got them, Captain. 800 yd in closing. Wait for it. Wait for it. The German fighters closed to 600 yd, then 500 yd. Now fire. The tail turret roared to life. Twin 50 calibers hammered out rounds at 850 rounds per minute. Tracers stre across the sky. The chin turret joined in. Then the [music] waist guns.

Then the dorsal turrets. Hedgehog became a storm of lead. For six solid minutes, the YB40 worked exactly as designed. Every attack broke [music] off early. Every enemy pilot kept their distance, unwilling to fly [music] through that curtain of fire. The bomber crews watching from nearby aircraft cheered over the radio. That thing’s a beast.

Did you see that? Tore apart. For a moment, just a moment, it looked like the flying destroyer might actually [music] work. At 4:47 p.m., the lead bombardier called bombs away. One by one, the B7s dropped their payloads. 500 lb bombs tumbling through the sky toward the submarine pens below. And just like that, each bomber became 4,000 lb lighter, faster, more maneuverable. They began to climb.

But Hedgehog didn’t. It still carried 11,000 rounds of ammunition, 4,000 extra pounds it couldn’t drop, couldn’t jettison, couldn’t get rid of. Hartwell pushed the throttles to maximum power. The engines screamed. Gauges crept into the red. Coolant temperatures spiked, but the formation pulled away.

1 mile, 3 m, 5 m, 7 m. Hedgehog was alone, and the German fighters knew it. Bandits inbound. 4:00 level, more at 9:00. [music] They’re everywhere. The lift buffer pilots had been watching. They’d seen the heavy bomber fall behind. They knew it was slow. They knew it couldn’t maneuver. And now they circled like wolves around wounded prey.

They attacked [music] from every angle, high, low, head-on, from the sides. The gunners fought back with everything they [music] had. The chin turret never stopped firing. Brass casings piled up on the floor. Barrels glowed red-hot. [music] One Faka Wolf 190 misjudged its pass and flew too close. The top turret gunner shredded its wing and it spiraled into the ocean.

But then another fighter came in from the right, [music] cannon shells punching through the wing. The hydraulic line to the right aileron exploded, spraying fluid [music] across the fuselage. The number three engine started losing orbital pressure. For 90 brutal minutes, Hedgehog fought alone. 90 minutes of dodging, weaving, firing, praying.

They made it across the channel [music] on three engines, leaking fuel with jammed trim tabs, and a dead radio. When they finally touched down at Alcenberry at 7:13 p.m., the crew sat in silence for a moment. Then they climbed out, legs shaking, faces pale. Colonel William Reed was waiting on the hard stand.

He walked up to Hartwell, who was leaning against the fuselage, wiping sweat [music] and oil from his face. Captain, your assessment. Hartwell looked at the damaged aircraft, at the scorched gun barrels, at the holes in the wing. He looked the colonel in the eye and said three [music] words that ended the dream. It can’t keep up. The Air Force didn’t give up immediately. They tried again.

Different tactics, different formations. They paired the YB40s [music] in teams. They positioned them in the center of the formation instead of the edges. They even tried having them drop [music] their ammunition cans mid-flight to reduce weight. Nothing worked. Over the next 3 months, YB40s flee 48 combat [music] sordies across seven missions.

Every single time, the same problem. Once the bombers [music] dropped their loads, the YB40s fell behind. Every single time, they fought their way home alone, outnumbered, [music] outmaneuvered, and barely surviving. In August 1943, the program was officially cancelled. Total cost $5.6 million. Total combat effectiveness zero.

On paper, [music] it was a complete failure. The most expensive mistake the Eighth Air Force ever made. But inside that failure was something no one expected. Something that would change the war. Engineers at right field were pouring over the combat [music] reports trying to figure out what went wrong.

And they noticed something. Every time a YB40 faced [music] a frontal attack, the deadliest threat to American bombers, it survived. The new Chin turret worked [music] flawlessly. Two 50 caliber guns mounted directly under the nose. Fully traversible, hydraulically powered. No blind spot [music] at 12:00 high.

German pilots couldn’t make a head-on run without flying straight into a wall of tracers. Boeing saw the reports. They saw the numbers. And in September [music] 1943, they made a decision that would save thousands of lives. They took the YB40’s [music] chin turret design and put it straight into production on their next model, the B17G.

[music] Everything changed. Before the chin turret, frontal attacks accounted for nearly [music] 40% of all bomber losses. Luftbuffa pilots would come screaming in from [music] 12:00 high, fire a burst of cannon shells straight through the cockpit and peel away before [music] the defensive guns could react.

After the B7G entered service, frontal attacks became suicide runs. Losses from head-on passes dropped by more than 70%. Crews who once expected to die before completing their 25 missions started making it home. Survival rates soared. But the YB40 gave the Flying Fortress more than just the chin turret. Engineers copied its staggered waist gun layout, giving gunners [music] room to move without tripping over each other, improving accuracy and field of fire.

They adopted the redesigned [music] Cheyenne tail turret, which offered better visibility and more protection for the tail gunner. Three innovations, three features born from a failed experiment. three changes [music] that would define the B17G, the most produced, most famous version of the Flying [music] Fortress ever built.

By the end of the war, over 8,600 B7Gs had been built. They flew over Berlin, over Munich, over Hamburgg. They dropped more than 640,000 tons of bombs on Nazi Germany. And every single one carried the DNA of the YB40, the bomber that couldn’t keep [music] up. Captain James Hartwell completed his 25 missions in October 1943. He survived the war and returned to the states as a flight instructor.

In the spring of 1944, he watched the first B7Gs arrive at the training base in Florida. New crews, fresh-faced kids, barely 20 years old, gathered around the aircraft, pointing at the chin turret and asking where it came from. Hartwell smiled. He lit a cigarette, leaned against the wing, and told them the truth from a bomber that couldn’t keep up.

The kids [music] laughed, thinking it was a joke. But Hartwell wasn’t joking. He knew the truth. He knew that failure had saved their lives. The YB40 disappeared [music] from history. No museum preserved one. No restoration project saved it. All 12 aircraft [music] were scrapped or converted back to standard bombers. But its legacy lived on.

In every B17G that flew over Germany, in every crew that made [music] it home, and every gunner that fired that chin turret and watched a German fighter break off its attack. History loves its heroes. We build [music] monuments to the successes. The flying fortresses that took brutal punishment and still brought their crews home. The Mustangs [music] that escorted them all the way to Berlin.

The men who flew 25 missions and came back alive. But the YB40 [music] reminds us of something we too often forget. Sometimes the most important victories come from failure. Sometimes the experiments that don’t work teach us more than the [music] ones that do. The flying destroyer didn’t win the war. It didn’t even survive the summer.

But the ideas it carried, the innovations born from [music] desperation and refined through failure. Those ideas saved thousands of lives. And maybe that’s the real lesson. Not that failure is acceptable, but that failure, when examined honestly, when learned from deeply, can be the beginning of something greater.

The YB40 proved that even disasters can leave behind legacies [music] worth remembering. If this story moved you, hit that like button so more people can discover it. Subscribe for [music] more forgotten stories of innovation, bravery, and the people who risked everything to test impossible ideas. Drop a comment. Tell us where [music] you’re watching from or if someone in your family served in World War II.

News

Japanese Troops Shocked by 12 Gauge Shotguns! D

November 2nd, 1943. Buganville Island, Solomon Islands. The jungle air hung thick as wet cloth against Private Tanaka’s face…

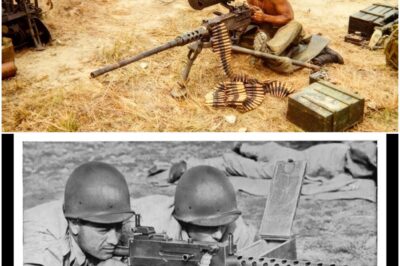

Japanese Soldiers Were Terrified When They Found U.S. Marines Used Machine Guns as Sniper Rifles D

On the morning of June 22nd, 1944, at 6:47 a.m., Corporal Jack McKver crouched behind his Browning M2 heavy…

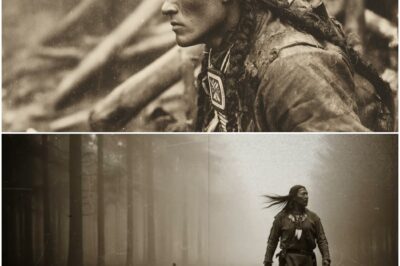

The Native Warrior Most Feared by the Germans in World War II D

Have you ever wondered what could make an entire German regiment refuse to advance even under direct orders from…

How One Navajo Soldier’s ‘CRAZY’ War Cry Made 52 Germans Think They Were Surrounded D

October 15th, 1944. The Voj mountains of eastern France stood wrapped in morning fog so thick that Lieutenant James…

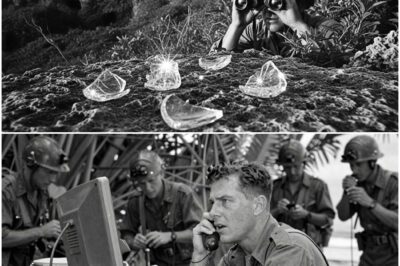

The “Broken Glass Method” That Let U.S. Snipers Spot 87 Hidden Japanese Soldiers in One Afternoon D

On the afternoon of September 14th, 1944, the tropical sun hung mercilessly over the dense jungle canopy of Paleu…

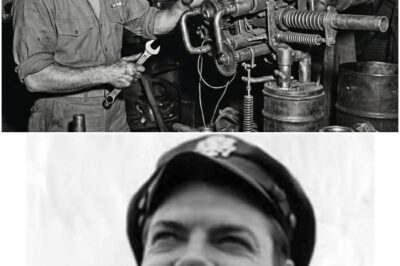

The “Mad” Mechanic Who Created the Weapon Japan Never Expected D

Imagine being trapped on a Pacific island, surrounded by thousands of Japanese soldiers, determined to destroy your position. Your…

End of content

No more pages to load