Jean Mark had been working at the Gran Hotel daper for six years. He’d served princes, presidents, and movie stars. He’d never made a mistake. Not once. Until the night he walked up to Robert Redford’s table and said the six words that would haunt him for the rest of his career.

The Great Escape is my favorite film of yours. Redford looked up from his vodka martini. For three seconds, he said nothing. Just stared at John Mark with those famous blue eyes. And Jean Mark’s brain started screaming. Wrong movie, wrong actor. That was Steve McQueen. Oh god, that was Steve McQueen. You just confused Robert Redford with Steve McQueen in front of Robert Redford.

John Mark felt his face burning. His hands started shaking in six years. He’d never made a mistake. And now he’d made the worst possible mistake with one of the most famous actors in the world at one of the most expensive hotels on the French Riviera in front of a dining room full of people who were definitely listening. This was it. His career was over.

Redford was going to complain to management. Jean Mark would be fired. Six years of perfect service, destroyed by six words. But what Robert Redford did next taught Jean Mark something about grace that he’d remember for 40 years. The Granotel Daparas sits on a peninsula between Nice and Monaco. It’s not just expensive.

It’s the kind of place where expense becomes invisible because if you have to ask, you can’t afford it. Rooms start at 1,500 euros a night. The wine seller holds bottles worth more than most people’s cars, and the clientele includes people whose names you’re not allowed to mention even after they leave. Jean Mark Rouso had worked there since 1998.

He started as a bus boy at 19. By 25, he’d become a full server in the main dining room, which was the pinnacle of his profession. The Grand Hotel didn’t hire servers. It cultivated them. Six months of training before you touched a table, another year before you served VIPs, and a lifetime of maintaining standards that most restaurants couldn’t imagine.

The unspoken rule was simple. Invisible perfection. Anticipate needs before they’re expressed. Never interrupt. Never intrude. Never ever make the guest feel anything except completely at ease. Jean Mark had mastered this. In six years, he’d served Saudi princes who tipped 5,000 euros. Tech billionaires who barely looked up from their phones.

Aging movie stars who wanted to be recognized but pretended they didn’t. And through it all, Jean Mark had been flawless. But he had one weakness, one tiny crack in his professional armor. He loved American movies. Not just loved them, he’d grown up watching them with his father. His father, Jacques, had been a projectionist at a cinema in Nice in the 1970s and 80s.

He’d bring home stories about the films, about the actors, about the golden age of Hollywood, and young Jean Mark would sit on the floor of their small apartment watching dubbed versions of Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid and The Sting, and all the president’s men falling in love with American cinema. His favorite actor was Steve McQueen, The Cool Rebel, The Motorcycle Rider, the man who jumped the fence in The Great Escape and became immortal.

Jean Mark must have watched that film 20 times. He could quote entire scenes. And in his teenage imagination, Steve McQueen represented everything heroic about American masculinity. But here’s the thing about watching movies as a kid in France in the 1980s and 90s. The films were dubbed. The actors all had French voices.

And sometimes when you’re 12 years old, all those blondhaired, blue-eyed American actors start to blur together. Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Steve McQueen, Warren Batty. They were all handsome, all cool, all iconic. And if you weren’t paying close attention to the opening credits, you might mix them up. Which brings us to April 2004, a Thursday evening.

Spring on the coat desour, which meant the weather was perfect, the hotel was full, and the dining room sparkled with wealth and beauty. Jean Mark was assigned to section 3, which included tables 8 through 12. Good tables, window views of the Mediterranean, the kind of section you earn through years of perfect service.

At 8:15 p.m., the Metro approached him discreetly. Jean Mark, table 10. Robert Redford and his wife. They’ve requested minimal interaction. Wine, dinner, privacy. Jean Mark felt a small thrill. Robert Redford, one of the legends his father had told him about, the Sundance Kid. He’d seen Butch Cassidy a dozen times.

He’d watched The Sting with his father the year before Jacques died. This was a connection to his childhood, to his father, to everything he loved about cinema. He approached Table 10 carefully, professional, invisible. Redford and his wife, Sibil, were looking at menus, speaking quietly in English.

Redford was 67 years old then, but he still had those eyes, the ones that had made him famous 50 years earlier, clear blue, almost unsettling in their intensity. “Good evening,” Jean Mark said in perfect English. “May I bring you something to drink?” Redford glanced up briefly. “Vodka martini, very cold. Three olives.

” His wife ordered white wine. Jean Mark nodded and disappeared. So far, so perfect. He returned with the drinks, placed them precisely, explained the evening’s specials, took their order, do soul for her, steak fre for him, medium rare. Jean Mark moved through the choreography of fine service like a dancer, remove the menus, refill the water, disappear.

But then, as he was turning to leave, something happened. A feeling, a warmth, a desire to connect. Maybe it was thinking about his father. Maybe it was the spring evening. Maybe it was just being 25 years old and having a chance to tell a childhood hero what his work had meant. Jean Mark made a decision that violated every rule of Grand Hotel service.

He spoke when he shouldn’t have. Mr. Redford, I hope you don’t mind, but I just wanted to say. He paused, smiling, feeling the excitement build. The Great Escape is my favorite film of yours. The motorcycle scene, incredible. My father and I watched it so many times. The words hung in the air for exactly one second before Jean Mark realized what he’d done.

And in that second, his entire world collapsed. Redford looked up from his vodka martini. Those blue eyes fixed on Jean Mark. 3 seconds of silence. 3 seconds that felt like 3 hours. And Jean Mark’s brain started screaming. Wrong movie. Wrong actor. That was Steve McQueen. Oh god. Oh god. That was Steve McQueen, not Redford. McQueen on the motorcycle jumping the fence.

How could you confuse them? How could you make that mistake? Jean Mark felt his face burning. Not just warm, burning, like someone had aimed a spotlight directly at his skull. His hands started shaking. The elegant composure he’d maintained for 6 years was evaporating in real time. He wanted to disappear. He wanted the marble floor to open up and swallow him whole.

Worse, he could feel the surrounding tables listening. The Grand Hotel dining room was designed for discreet conversations, but everyone always paid attention when something unusual happened. And a waiter speaking to Robert Redford. That was unusual. A waiter saying something wrong to Robert Redford. That was theater.

Jean Mark opened his mouth to apologize, to correct himself, to say, “I’m so sorry. I meant” But nothing came out. He was frozen, trapped in the worst moment of his professional life. Six years of perfect service, six years of invisible perfection, destroyed by six words, six stupid, wrong, humiliating words.

This was it. His career was over. Redford was going to complain to management. The Metro D would pull him aside. Jean Mark, I’m sorry, but we can’t have servers who make mistakes like this. He’d be back to busing tables or worse, he’d be fired, six years gone. All because he couldn’t keep his mouth shut. All because he’d confused Steve McQueen with Robert Redford like some tourist who’d never seen a movie in his life.

But what Robert Redford did next changed everything. Redford held John Mark’s gaze for those three eternal seconds. Then his expression softened. And he smiled. Not a fake smile, not a polite smile, a real warm, genuine smile. “Thank you,” Redford said quietly. “That means a lot. Jean Mark blinked.

Wait, what? Redford continued, his voice gentle. My father took me to see that film when I was young. The cinematography was beautiful, and that motorcycle scene, you’re right, incredible. Thank you for remembering it. Then Redford raised his vodka martini slightly, a tiny toast, and took a sip. The conversation was over.

Jean Mark was dismissed, but not in anger, not in correction, just dismissed. The way you dismiss someone after they’d said something nice. Jean Mark walked back toward the kitchen in a days. His hands were still shaking, but now for a different reason. What had just happened? Redford had thanked him for praising the wrong movie. The movie Redford wasn’t even in.

Had Redford not heard him correctly? Had John Mark said something different than he thought? No, he definitely said the great escape. He definitely mentioned that the motorcycle scene there was no ambiguity. Redford had heard him. Redford knew. Robert Redford, who’d spent 50 years in Hollywood, who’d worked with Steve McQueen, who’d been confused with Steve McQueen a hundred times, definitely knew that The Great Escape wasn’t his film.

But he’d said thank you anyway. He’d smiled. He’d even expanded on Jean Mark’s comment talking about the cinematography, about his father, about the motorcycle scene. As if Jean Mark had been right, as if the mistake had never happened. Jean Mark stopped in the corridor between the dining room and the kitchen. He leaned against the wall and slowly, very slowly, he understood what had just happened.

Robert Redford had seen John Mark’s face, had seen the panic, had seen the burning embarrassment, had seen a young man who just made a terrible mistake in front of a dining room full of people. And Redford had made a choice, a split-second choice. He could correct John Mark. Could say, “Actually, that was Steve McQueen.

” Could make it a teaching moment, a gentle correction, the classy thing to do. Or he could do something else, something that required more grace, more generosity, more emotional intelligence. He could pretend the mistake never happened. He could accept the compliment as if it were accurate. He could thank Jean Mark, smile at him, and send him away with his dignity intact.

That’s what Redford had done. He’d chosen kindness over accuracy, ego over grace. He’d let Jean Mark keep his dignity at the cost of what? Nothing. Absolutely nothing. Redford lost nothing by not correcting him, but Jean Mark gained everything. The rest of the evening passed in a blur. Jean Mark served the meal.

Dover soul, steak, fruit, dessert, coffee, the check. Redford and his wife left around 10:30 p.m. Redford nodded to Jean Mark on his way out. Excellent service. Thank you. Jean Mark nodded back, unable to speak. After the dining room closed, Jean Mark sat in the staff break room with another server, Antoine. You okay? Antoine asked.

You’ve been quiet all night. Jean Mark hesitated. Then he told the story. The mistake, the panic. Redford’s response. Antoine listened, then shook his head slowly. You got lucky. Most actors would have corrected you. Made it a joke. Made everyone laugh. Made you feel small even while pretending not to. But Jean Mark disagreed.

I don’t think it was luck. I think that’s just who he is. Over the next few weeks, Jean Mark couldn’t stop thinking about that moment. He researched Robert Redford, read interviews, watched documentaries, and he found a pattern. Stories of Redford deflecting credit, refusing awards, staying quiet when other actors took credit for his ideas, choosing privacy over publicity, choosing substance over ego.

There was the story of Redford building Sundance Film Festival specifically to elevate unknown filmmakers, never putting his own name above theirs. The story of him buying hundreds of acres in Utah and immediately protecting them from development instead of building a mansion. The story of him turning down roles in massive blockbusters to direct small personal films that barely made money. A picture emerged.

Robert Redford was a man who’d spent his entire career trying not to be the center of attention, which was ironic because he was one of the most famous actors in the world. But fame hadn’t made him need validation. It had made him more careful about taking up space, more aware of his power, more intentional about using it gently.

And that’s what he’d done for Jean Mark. He’d seen a young man having the worst moment of his professional life. And instead of asserting his own knowledge, his own correctness, his own ego, Redford had simply let it go. Let the mistake slide. Let Jean Mark walk away with his pride intact. That level of grace is rare, especially in Hollywood, especially in a culture that rewards being right, being smart, being the one who knows more.

Redford could have corrected John Mark and still been kind about it. Could have said that was actually Steve McQueen, but I love that film, too. who could have made it light and funny and fine, but even that would have required John Mark to absorb the correction, to feel the sting of being wrong, to walk away knowing that everyone at the nearby tables had heard his mistake and heard the correction.

Redford chose a different path. He chose to absorb the mistake himself. To let people think he was in the great escape, if that’s what they believed, to sacrifice accuracy for kindness. That’s a level of security that most people never reach. The security to be wrong. The confidence to let others think you’re confused.

The strength to protect someone else’s dignity at the cost of your own correctness. Jean Mark worked at the Grand Hotel for another 12 years. He served countless celebrities, actors, musicians, politicians, royalty, and he learned to recognize a pattern. The truly secure ones never corrected you.

The ones who needed validation always did. The difference wasn’t about intelligence or knowledge. It was about ego, or rather the lack of it. He saw famous actors correct pronunciation of their names with irritation. Saw politicians correct facts about their careers with condescension. Saw billionaires correct details about their companies with barely concealed contempt.

And each time, Jean Mark remembered Robert Redford, remembered the 3 seconds of silence, remembered the smile, remembered the choice to be kind instead of right. In 2016, John Mark left the GR hotel. He’d gotten married, had two children, wanted more time with his family. On his last night during the farewell dinner the staff threw for him, someone asked, “What’s the most important thing you learned working here?” Jean Mark didn’t hesitate.

April 2004, Robert Redford taught me that the strongest people are the ones who can let mistakes slide. That real confidence means you don’t need to prove you’re right. That grace costs you nothing and gives someone else everything. He paused, then added, “I made the stupidest mistake of my career that night.” Confused him with Steve McQueen.

And he could have humiliated me, could have corrected me, could have made it funny or awkward or educational, but instead he just let it go. let me keep my dignity. And that taught me more about character than six years of perfect service ever did. The lesson of that night wasn’t about Robert Redford being nice.

It was about the difference between ego and grace. Ego needs to be right, needs to correct, needs to be seen as knowledgeable and accurate. Grace just lets things go. Lets people have their moment. Lets mistakes slide. Because being kind matters more than being correct. Hollywood is full of egos. That’s not a criticism. That’s survival.

You need ego to become famous, to demand the roles you want, to negotiate the contracts you deserve, to believe you’re good enough to be on screen in front of millions. But the rare ones, the truly secure ones, learn to turn that ego off when it serves someone else better. Robert Redford turned his off that night, saw a young man’s panic, and thought, “I can fix this. I can make this okay.

All I have to do is pretend I don’t know the difference between my films and Steve McQueen’s films. The cost, nothing. His ego wasn’t damaged. His reputation wasn’t harmed. Nobody thought less of him. The benefit. Jean Mark walked away with his career intact. His dignity preserved. His faith in human kindness restored.

That transaction, that choice, that moment of grace, it rippled outward. Jean Mark treated guests differently after that night with more patience, more generosity, more willingness to overlook small mistakes because he’d been shown that mercy himself. And the guests he treated that way. Some of them went home and treated their employees differently, their families differently, their strangers differently. That’s how grace works.

It multiplies. Robert Redford probably doesn’t remember that night. Why would he? It was one dinner among thousands, one interaction among millions. But John Mark Rouso has told this story a hundred times. At dinner parties, at family gatherings, to his children when they come home from school upset about being embarrassed.

Let me tell you about the time I confused Robert Redford with Steve McQueen and what he taught me about grace. The story always ends the same way. The greatest people aren’t the ones who prove they’re right. They’re the ones who choose to be kind instead. And that night, Robert Redford chose kindness for no reason except that he could.

And that’s why he’s not just a legend of cinema. He’s a legend of character. If this story of choosing grace over ego moved you, share it with someone who needs to remember that being kind matters more than being right. Have you ever witnessed or experienced a moment when someone chose your dignity over their own correctness? Let us know in the comments and subscribe for more untold stories about the quiet moments that reveal true character.

News

“Jeremiah Johnson” crew STRANDED at 11,000 feet — what Redford did next SAVED their lives

Sydney Pollock was screaming into a dead radio. We need helicopters now. We have 40 people freezing to death up…

Paul Newman DESTROYED Redford’s trailer on set — Redford’s revenge became LEGENDARY

Robert Redford opened his trailer door on the set of The Sting and stopped cold. Every single inch of the…

Sydney Pollack FIRED Redford mid-scene — Redford’s response STUNNED the entire crew

Get off my set. The words hung in the air like a gunshot. Sydney Pollock, one of Hollywood’s most respected…

“Stunt explosion went WRONG on set — Redford’s 3-second decision saved a man’s LIFE”

The explosion was supposed to go off at 3:47 p.m. It went off at 3:46. 1 second early doesn’t sound…

How One Engineer’s “Stupid” Idea Turned U.S. Paratroopers Into Tank Killers

Aberdine Proving Ground, Maryland. May 12th, 1942. The morning mist hung over the test range as five different anti-tank weapons…

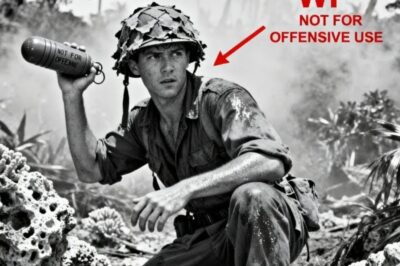

Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day

May 18th, 1944. Biak Island, Dutch New Guinea. Private First Class. Harold Moon crouches behind a shattered palm tree as…

End of content

No more pages to load