The explosion was supposed to go off at 3:47 p.m. It went off at 3:46. 1 second early doesn’t sound like much, but on a film set, 1 second is the difference between a stunt and a death. Utah, 1972. Robert Redford was filming Jeremiah Johnson in the mountains. The scene, a cabin explodes, the stunt man runs out.

Camera captures it. Simple. Except the pyrochnics team made a mistake. The charges were wired wrong. The timer was off and the stunt man, a 29-year-old named Michael Runyard, was still inside the cabin when the director called action. The explosion triggered early. 60 ft of lumber, glass, metal, all turning into shrapnel, moving at 400 mph.

Michael was three steps from the door when it blew. The entire crew froze, paralyzed, watching a man about to die. Everyone except Robert Redford. What Redford did in the next three seconds saved Michael’s life, but it also nearly ended his own because Robert Redford didn’t think. He just ran straight into an exploding building.

To understand what happened in those three seconds, you need to understand what was happening in Robert Redford’s life in 1972. He was 36 years old. He’d been in Hollywood for a decade. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid had made him a star three years earlier. He was handsome, charismatic, bankable. But there was a problem.

Hollywood saw him as just a pretty face, a leading man, not an actor, certainly not someone substantial. Redford hated this. He didn’t want to be a movie star. He wanted to be taken seriously. He wanted to make films that mattered, films that said something about the American experience, about survival, about character.

That’s why Jeremiah Johnson was so important to him. It was based on the real story of a mountain man in the 1850s. A man who lived alone in the wilderness who who survived on skill and determination, who didn’t need Hollywood, who didn’t need anyone. Redford saw himself in that character. The film was being shot in the Wasach Mountains of Utah.

Brutal conditions, freezing temperatures, thin air at 8,000 ft elevation, real wilderness, no sound stages, no comfort. The cast and crew lived in tents. They hiked miles every day to reach locations. It was physically punishing. But Redford insisted on it. He wanted authenticity. He wanted to prove he could handle it.

The director was Sydney Pollock, Redford’s friend. They’d worked together before. They trusted each other. But even Pollock was worried about some of the stunts, explosions, horseback chases, hand-to-hand combat. Redford insisted on doing as much as possible himself. He wanted to embody the character, to feel what Jeremiah Johnson felt. That meant risk.

October 18th, 1972. The crew had been shooting for 6 weeks. They were behind schedule. The weather was getting worse. Winter was coming to the mountains. They needed to finish the explosive scenes before snow made filming impossible. The scene that day involved a Crow Indian raid on a cabin.

The cabin needed to explode dramatically. Fire, smoke, timber flying. Very visual, very dangerous. The pyrochnics team had arrived two days earlier. They’d planted charges throughout the cabin structure. Small controlled explosions designed to look massive on camera. The key was timing. The stunt man playing a settler needed to run out of the cabin.

The director would call action. The stunt man would burst through the door and exactly 4 seconds later, the charges would blow. 4 seconds. That was the safety window. But there was a complication. The pyrochnic supervisor was new. His name was Harold Wesson. He’d worked on smaller productions, but never anything this remote. Never anything at this altitude.

The thin air changed how explosives behaved. The cold affected the wiring. Harold knew this. He tested the charges. He triple checked the connections. He was confident. He was wrong. Michael Runyard was the stunt man. 29 years old. Former rodeo writer from Wyoming. He’d been working in films for five years.

mostly westerns, mostly practical stunts, falls, fights, horsework. He was good at his job, professional, careful. He’d survived dozens of dangerous scenes. He trusted the pyrochnics team. That trust would nearly kill him. The morning of October 18th was clear, cold, beautiful. The cabin was ready. The cameras were positioned.

The crew was in place. Sydney Pollock went over the shot with Michael one more time. You run out the door hard, fast, like you’re escaping death because on screen you are. You have 4 seconds after I call action. 4 seconds to get clear. The explosion happens behind you. We capture it. One take. Got it. Michael nodded. Got it. Redford was standing nearby.

He wasn’t in the shot. He was just watching, observing how Sydney worked, learning. He directed some television. He wanted to direct films someday. He paid attention to everything. How Sydney positioned cameras. How he communicated with actors. How he managed risk. The crew did a rehearsal without explosives. Michael ran through the door, timed his steps, found his mark.

Everything looked good. Harold Wesson checked the wiring one last time, checked the timer, confirmed with his assistant that everything was synced. The charges would blow exactly 4 seconds after Sydney called action. Not three, not five, four. Precise. Sydney called everyone to positions. This is the real take. Michael, when you’re ready, signal on action, you run.

Cameras rolling, everyone quiet. Michael stepped into position inside the cabin. He could see the charges planted around the walls, small packs of explosives connected by wires. They looked harmless. He knew they weren’t, but he trusted Harold. Harold had done this a hundred times. Michael gave the signal. Thumbs up. Ready. Sydney raised his hand.

And action. Michael exploded through the door, running hard, powerful strides. He was fast, athletic. He covered 10 feet in the first second. 20 feet in two seconds. He was going to make it easily. 4 seconds was plenty of time. But at 3:46 p.m., something went wrong. A wire connection that Harold had checked. A timer that Harold had tested.

A system that Harold had trusted. It failed. The charges received the signal 1 second early. 1 second, not 4 seconds after action, 3 seconds after action. Michael was at 30 ft, not 40. Still too close. The explosion was massive, much bigger than planned. The charges had been designed to blow sequentially, small bursts creating the illusion of one large explosion.

But when the timing failed, all the charges blew simultaneously. 60 ft of cabin lumber. Every window, every support beam, all exploding at once. The force was incredible. The sound was deafening. Michael felt the blast wave hit his back. It threw him forward. He stumbled, nearly fell. Splinters of wood flew past his head. Shards of glass, chunks of metal hardware.

The cabin was disintegrating behind him, turning into a cloud of shrapnel moving at hundreds of miles per hour. 30 feet away seemed far. It wasn’t far enough. The crew stood frozen. Sydney Pollock’s mouth hung open. The camera operators kept filming on instinct, but everyone knew what they were seeing. Michael was in the kill zone. The collapsing structure was going to crush him.

The flying debris was going to tear through him. They were watching a man die. That’s when Robert Redford started running. He didn’t think, didn’t calculate, didn’t weigh the risk. He just ran straight toward the explosion, straight toward the collapsing cabin, straight toward Michael. The crew started shouting, “Stop! Don’t! You’ll die, too.

” Redford didn’t hear them, or he heard and didn’t care. He was running on pure instinct. The same instinct that makes firefighters run into burning buildings, that makes soldiers jump on grenades, that makes humans protect other humans. Redford was 30 yards away when he started running. Michael was stumbling forward, but not fast enough.

The cabin was collapsing, timber falling, the roof line coming down. Redford ran faster than he’d ever run. His boots pounded the dirt. His breath came in gasps. The thin mountaine air burned his lungs. He didn’t slow down. 3 seconds. That’s how long it took Redford to cover 30 yards. 3 seconds to make a decision that could end his career. End his life.

He reached Michael just as a massive roof beam fell. 20 ft long, 200 lb. Coming down right where Michael was standing. Redford grabbed Michael’s jacket, yanked him forward, threw him toward safety. The beam hit the ground exactly where Michael had been one second earlier. But Redford wasn’t clear. He’d pushed Michael to safety, but momentum carried him into the collapse zone.

A support post fell. Redford dodged left. A sheet of corrugated metal spun through the air. Redford ducked. The cabin was disintegrating around him. Fire, smoke, flying debris. He was in the middle of it. Sydney Pollock screamed, “Get out! Robert! Get out!” Redford scrambled forward. A wall section collapsed behind him, missed him by inches.

Glass rained down, cut his neck, his hands. He kept moving, diving, crawling, fighting his way through the destruction. And then he was clear, rolling in the dirt, 30 ft from the collapse, breathing, bleeding, alive. The crew rushed forward. Michael was on his knees, shaking, bleeding from cuts on his face and arms, but alive, conscious.

Redford was lying on his back, staring at the sky, blood trickling from cuts on his neck and hands, but nothing serious, nothing life-threatening. The medic ran over, checked them both. minor injuries, lacerations, shock, but they’d survive. Sydney Pollock knelt beside Redford. His face was white. His hands were shaking.

What the hell were you thinking? You could have died. Both of you could have died. Redford sat up slowly. He looked at Michael, then at Sydney. I wasn’t thinking. I just saw him and I ran. Cydney stared at him. That was the stupidest, bravest thing I’ve ever seen. The crew gathered around, silent, processing what they’d just witnessed.

One of the camera operators was crying. A grip was throwing up from adrenaline. Harold Wesson stood apart from the group, his face buried in his hands. He’d nearly killed two people. Michael Runard walked over to Redford, helped him to his feet. They stood there for a moment.

Two men who’ just survived death together. Michael tried to speak, couldn’t find words. Finally managed to say thank you. It came out as a whisper. Redford shook his head. Don’t thank me. I didn’t think about it. Michael smiled weakly. That’s why I’m thanking you. If you’d thought about it, you wouldn’t have done it. They both started laughing, nervous, shocked, alive.

The crew joined in, laughter mixed with tears. Relief. The kind of emotional release that comes after near death. Production shut down for 3 days. The studio sent investigators. They examined the pyrochnics equipment, found the wiring error, a reversed connection, a timer that had been set incorrectly, simple mistakes, but nearly fatal.

Harold Wesson was devastated. He resigned, left the film industry. Couldn’t live with what had almost happened. The pyrochnics team was replaced. Safety protocols were reviewed, enhanced. The cabin scene was reshot two weeks later. Different location, different setup, no explosions. They used editing tricks instead.

But something had changed on that set. The crew looked at Robert Redford differently. He wasn’t just a movie star anymore. He wasn’t just a pretty face. He was someone who’d proven his character when it mattered most. Someone who valued human life over self-preservation. Someone real. Michael Runyard stayed in touch with Redford for the rest of his life. They became friends.

Not close friends. They lived in different worlds, but friends nonetheless. Every year on October 18th, Michael would call Redford. Thank him again. Redford would always say the same thing. I just did what anyone would do. But Michael knew better. He’d been in that crew. He’d seen 30 people freeze. Only one person had run toward the danger.

Jeremiah Johnson was released in 1972. It was a modest success. Critics praised Redford’s performance. Audiences appreciated the authenticity, the rugged beauty of the Utah Mountains, the honest portrayal of survival. But nobody watching that film knew what had happened during production, the explosion that nearly killed two men.

The 3 seconds that proved who Robert Redford really was. Years later, in interviews, Redford would downplay the incident. He’d say it was instinct, that he didn’t think about it, that anyone would have done the same, but the people who were there disagreed. Sydney Pollock told the story often.

He’d say it was the moment he realized Redford wasn’t just talented. He was substantial. He had depth. He had courage that went beyond acting. The incident changed Redford’s approach to film making. He became more safety conscious, more protective of his crews. When he started directing his own films, he insisted on thorough safety reviews.

He refused to take unnecessary risks, not because he was afraid, but because he understood the consequences. He’d seen how close death could come, how quickly things could go wrong, how one second could be the difference between life and death. Michael Runard worked in films for another 20 years. He did hundreds of stunts.

But he never forgot October 18th, 1972. He never forgot the feeling of that explosion hitting his back, the terror of stumbling forward knowing he wasn’t going to make it. And then the sudden pull, Redford’s hand on his jacket, the yanking motion that threw him clear. Those three seconds gave him 20 more years of life, 20 years of sunrises, of laughter, of family, of love.

In 1992, Michael retired from stunt work. He’d survived too many close calls. His body was wearing out, but he was grateful. He’d had a career. He’d raised children. He’d lived a life. All because Robert Redford had run toward an exploding building instead of away from it. In his retirement, Michael wrote a letter to Redford.

He’d written many letters over the years, but this one was different. This one he actually sent. The letter was simple. It thanked Redford for those three seconds. It acknowledged that Redford probably didn’t want to be thanked. Didn’t want to be called a hero, but Michael needed to say it anyway. Needed Redford to understand what those three seconds had meant.

They hadn’t just saved Michael’s life. They’d given him 20 more years of living. And that was everything, Redford wrote back. His response was brief. I’m glad you’re okay. I’m glad you had those 20 years. And I meant what I said. I just did what anyone would do. But Michael kept that letter, framed it, hung it in his home office because it reminded him that sometimes anyone means someone very specific.

Someone who runs when everyone else freezes. The story of what happened on October 18th, 1972 never became widely known. It wasn’t in the press. It wasn’t in biographies. It was just a story that the Jeremiah Johnson crew told, that Michael told his family, that Sydney Pollock mentioned occasionally, a footnote in Robert Redford’s career.

But to the people who were there, it was something more. It was the moment they saw who Robert Redford really was. Not the Sundance kid, not the movie star, not the pretty face that Hollywood had tried to make him. A man who understood that some things matter more than fame, more than safety, more than career, like keeping someone alive.

3 seconds doesn’t sound like much. It’s barely enough time to make a decision, barely enough time to act. But sometimes 3 seconds is all you get. Three seconds to choose between watching or doing, between freezing or running, between being a bystander or being human. Robert Redford had three seconds. He chose to run.

And in doing so, he saved a life. Nearly lost his own and proved something to everyone watching. That real courage isn’t about not being afraid. It’s about being afraid and running toward the danger. Anyway, Michael Runard died in 2003. Natural causes. He was 60 years old. He’d lived 31 years after the explosion. 31 years he wouldn’t have had without those 3 seconds.

His obituary mentioned his stunt work, his films, his family. But it didn’t mention October 18th, 1972. It didn’t mention Robert Redford. That story was too personal, too private, too sacred. It was between two men who’d faced death together and survived. Robert Redford continues his work today. He’s directed films, founded Sundance, championed independent cinema, won awards.

But if you ask the people who know him best what defines him, they’ll tell you different stories. Stories about integrity, about standing up for what’s right, about protecting the vulnerable, about running toward danger when everyone else runs away. Because that’s who Robert Redford is, not a movie star, a man who understands that being human means sometimes you just run.

You don’t think, you don’t calculate, you just see someone who needs help and you run, even if it might cost you everything. That’s the lesson of October 18th, 1972. That’s what those three seconds taught everyone who was there. That courage isn’t the absence of fear. It’s the decision to act despite fear. It’s the choice to value someone else’s life as much as your own.

It’s the willingness to risk everything for someone you barely know. Because that’s what humans do. At least the best humans, the ones who understand that some things are worth dying for, like keeping someone else alive. If this story of 3 seconds that changed two lives moved you, remember that everyday moments can become defining ones.

We all face choices. Most aren’t as dramatic as running into an exploding building, but their choices nonetheless.

News

Waiter praised Redford for WRONG MOVIE at Grand Hotel — his response was warmed hearth

Jean Mark had been working at the Gran Hotel daper for six years. He’d served princes, presidents, and movie stars….

“Jeremiah Johnson” crew STRANDED at 11,000 feet — what Redford did next SAVED their lives

Sydney Pollock was screaming into a dead radio. We need helicopters now. We have 40 people freezing to death up…

Paul Newman DESTROYED Redford’s trailer on set — Redford’s revenge became LEGENDARY

Robert Redford opened his trailer door on the set of The Sting and stopped cold. Every single inch of the…

Sydney Pollack FIRED Redford mid-scene — Redford’s response STUNNED the entire crew

Get off my set. The words hung in the air like a gunshot. Sydney Pollock, one of Hollywood’s most respected…

How One Engineer’s “Stupid” Idea Turned U.S. Paratroopers Into Tank Killers

Aberdine Proving Ground, Maryland. May 12th, 1942. The morning mist hung over the test range as five different anti-tank weapons…

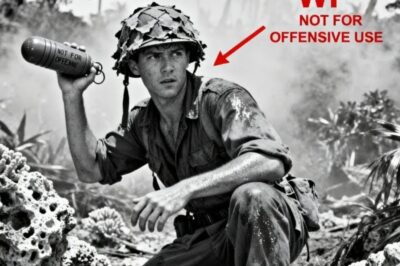

Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day

May 18th, 1944. Biak Island, Dutch New Guinea. Private First Class. Harold Moon crouches behind a shattered palm tree as…

End of content

No more pages to load