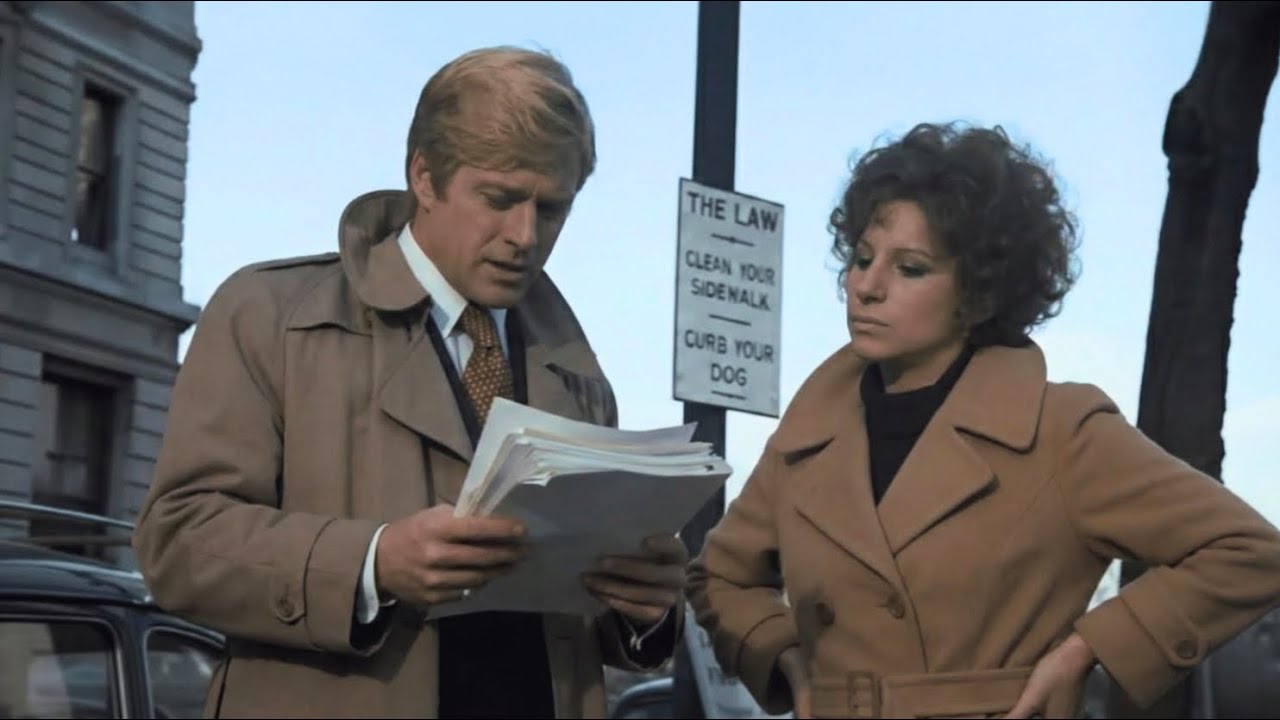

Final scene. The Way We Were. New York Street, 1973. Redford refuses to say his lines. Two pages of dialogue. Gone. Sydney Pollock is furious. Barbara Streryand is confused. The crew is waiting. What are you going to do instead? Pollock asks. You’ll see. Redford says action. Redford doesn’t speak for 30 seconds.

He does something else. Something wordless. Barbara reacts. Real tears, not acting anymore. Sydney keeps the camera rolling. The crew realizes they’re witnessing something extraordinary. When Pollock calls cut, the set is silent. Everyone knows they’ve just captured the most perfect ending in cinema. But what did Redford do? What replaced two pages of carefully written dialogue? And why did that silent moment become more powerful than any words could have been? The answer changed how Hollywood understood acting, changed what it meant

to tell the truth on screen. 1972, Columbia Pictures green lit The Way We Were, a love story spanning 20 years. Katie Moroski, a passionate Jewish political activist. Hubble Gardener, a golden wasp writer who glides through life on charm and talent. They fall in love in college, separate. Reconnect in Hollywood during the Blacklist era.

Marry, have a child, then realize their differences are too fundamental to overcome. The script had everything. Romance, politics, the McCarthy era, two people who love each other but can’t make it work. It was ambitious, risky, exactly the kind of prestige picture Hollywood wanted. Sydney Pollock signed on to direct.

He’d worked with Redford before on This Property is Condemned and Jeremiah Johnson. They understood each other, trusted each other, but they also knew how to fight. Casting Katie was crucial. She needed to be strong, passionate, difficult. Someone who could match Redford star power and hold her own. Barbara Streend was offered the role.

She’d never done a straight dramatic romance before. She was known for musicals, for her voice, for being larger than life. But Pollock saw something else in her. Intensity, intelligence, the ability to make Katie real. Redford and Streryand met for the first time at a script reading. The chemistry was immediate but complicated. Redford was laid-back, instinctive, minimal.

Barbara was precise, technical, questioning everything. They were opposites, which made them perfect for Katie and Hubble. Production began in fall 1972, filming on location at Union College in Skenctity for the 1930s college scenes, then California, then New York for the final scenes. From the beginning, the script was a problem. Not because it was bad, because it was too much, too explanatory, too literal.

Writer Arthur Lawrence had crafted beautiful dialogue, but but sometimes beautiful dialogue gets in the way of truth. Redford felt it early. His character Hubble was supposed to be golden, easy, someone who didn’t overthink. But the script kept making him articulate his feelings, explain his choices, defend his decisions.

That wasn’t Hubble. Hubble doesn’t talk this much, Redford told Pollock during rehearsals. The audience needs to understand his perspective, Pollock replied. They’ll understand from what he doesn’t say. It became an ongoing tension. Pollock wanted dialogue. Redford wanted silence. Barbara, caught between them, tried to mediate.

She understood both sides. The script needed words to move the plot forward. But Redford was right that sometimes actors communicate more through silence than speech. The production was difficult. Redford and Stryand’s different approaches caused friction. He wanted spontaneity. She wanted precision.

He learned lines but changed them. She learned lines and expected them to be spoken exactly as written. They argued, not hostile, but intense. Pollock mediated constantly, keeping the peace, pushing both actors to their best work. It was exhausting, but effective. The tension between Redford and Strson translated into tension between Hubble and Katie.

The love felt real because the difficulty felt real. By early 1973, they reached the final scenes. Katie and Hubble have divorced. Years have passed. Katie is remarried, politically active as ever. Hubble has moved on, writing for television, dating a simpler woman who doesn’t challenge him. They run into each other by chance outside the Plaza Hotel in New York.

Their last conversation. The script for this scene was lengthy. Two pages of dialogue. Katie explains why she couldn’t change. Hubble explains why he had to. They talk about what they had, what they lost, why it couldn’t work. It’s articulate, thoughtful, complete. Arthur Lawrence, the screenwriter, considered it some of his best work.

Every line earned, every sentiment true. He’d spent months perfecting this ending. Pollock scheduled three days to shoot the final scene. Location: Fifth Avenue and 59th Street outside the plaza. They needed permits, crowd control, multiple takes. This was the emotional climax of the entire film. Everything had to be perfect.

The night before filming, Redford called Pollock. Sydney, I need to talk about tomorrow. What’s wrong? The dialogue, the final scene. It’s too much. Pollock felt a familiar frustration. They’d been through this before. Bob, it’s the ending. We need to give the audience closure. I know, but these lines don’t feel like Hubble. He wouldn’t explain himself this way.

He just Redford paused. He’d just be present, be there with her, feel it, but not talk about it. What are you suggesting? I don’t know yet. But I know if I say all those lines, we’ll lose something. We’ll make it smaller. Pollock was quiet. He trusted Redford’s instincts. But this was the ending. The moment the entire film built toward taking a risk here could ruin everything or make it transcendent.

Show me onset tomorrow. Pollock finally said, “Before we roll, show me what you’re thinking.” The next morning, March 1973, cold in New York. The crew set up on Fifth Avenue. Pedestrians walked by curious about the film shoot. Barbara arrived in costume, simple clothes. Katie had moved on from Hollywood glamour. She was herself now, authentically herself.

Redford arrived and pulled Pollock aside about the dialogue. Yeah, I want to cut most of it, keep the essential moments, but the rest I think we should just let the scene breathe. Pollock looked at the script. Two pages of careful dialogue. He thought about Arthur Lawrence, who’d be furious, about Colombia Pictures, who who’d green lit this based on that script, about the audience who’d want closure.

Then he thought about every time Redford’s instincts had been right, about the way he understood Hubble in ways even the writer didn’t. About how the best moments in film often happened when actors stopped performing and started being. “Okay,” Pollock said. “We’ll try it your way first. If it doesn’t work, we’ll shoot the scripted version,” Barbara approached.

“Are we ready?” “Small change,” Pollock said. “Bob’s going to trim some dialogue.” Barbara looked at Redford. She’d learned to trust him over these months, even when his approach baffled her. How much are we trimming? Most of it, Redford said quietly. [snorts] Most of it, Barbara’s voice rose. Sydney, the scene is the dialogue.

That’s what we’ve been building toward. I know, Redford said. But Hubble wouldn’t say all those things. He He’d want to. He’d feel them, but he wouldn’t say them. So, what will you do? I’ll be there with you. I’ll listen. I’ll respond. Just not with words. Barbara stared at him. This was insane. They were shooting the most important scene in the film, and the leading man wanted to improvise, but something in Redford’s eyes told her he was right. She’d learned that look.

He had something. “Okay,” she said. “Let’s try it.” They rehearsed the blocking. Barbara would walk up carrying flyers for a political cause. She’d see Hubble across the street. They’d approach each other, have their final conversation. In the script, it was pages of dialogue. Now it would be something else.

Quiet on set, the assistant director called. The crew settled, cameras ready, sound rolling. This was it. Action, Pollock called. Barbara walked into frame, carrying her political flyers. Katie Moroski, older now, still fighting, still passionate. She saw someone across the street. Hubble. Her face changed. Pain, joy, history.

Everything they’d been to each other compressed into that recognition. She crossed to him. Redford stood there. Hubble, still golden, still easy. But there was sadness in his eyes. The cost of choosing the comfortable life over the meaningful one. Hubble, Barbara said. Her voice carried everything. The years, the love, the loss. Katie, Redford replied, just her name.

Nothing more needed. They stood looking at each other. The script called for Barbara to launch into her explanation. why she couldn’t change, why she had to keep fighting, why their love wasn’t enough. Barbara started, delivered her lines, beautiful, articulate lines about principle and passion. Redford listened, really listened, the way Hubble would, the way a man listens to a woman he loved and lost because they wanted different lives.

Then came Redford’s turn. his big speech, two pages explaining Hubble’s side, why he chose ease over difficulty, why he needed someone who didn’t challenge him every moment, why he’d always loved Katie but couldn’t live with her. Redford opened his mouth, then stopped, looked at Barbara, at Katie, this woman he’d loved, this force he couldn’t contain.

All those words in the script were true, but Hubble wouldn’t say them. He’d feel them, carry them, but not speak them. Instead, Redford did something simple. He reached out gently and brushed Katie’s hair back from her face. “The way you touch someone you loved, someone you lost, someone who’s still beautiful to you, even though you’ve chosen different paths.

” It lasted maybe 3 seconds in his hand touching her hair. Tenderness, regret, acceptance. Everything the two pages of dialogue tried to say contained in that one gesture. Barbara’s eyes filled with tears. Real tears. She wasn’t acting anymore. She was Katie, feeling Hubble’s goodbye, feeling him choose to let her go again.

“Your girl is lovely, Hubble,” Barbara said, her final scripted line. Redford smiled. “Sad.” “True, I know.” They looked at each other one more time. Everything they couldn’t say hung in the air. Then Barbara turned and walked away. back to her life of passion and principle. Redford watched her go back to his life of ease and compromise.

Pollock kept the cameras rolling, watching this moment unfold. He’d been ready to call cut after Redford’s big speech, but there was no speech. Just that gesture, that touch, that wordless goodbye. “Cut,” Pollock finally said. The set was completely silent. Crew members stood frozen. The camera operators, the sound guy, the AD, everyone had felt it.

That moment when acting stops and truth takes over. Barbara wiped her eyes. Was that okay? Pollock couldn’t speak, just nodded. Redford stood there, still in character, still feeling Hubble’s goodbye. We should do another take, the script supervisor said, checking her notes. He didn’t say his lines. No, Pollock said firmly. We got it.

But the dialogue, we don’t need the dialogue. That was perfect. They shot a few more takes. Safety coverage, different angles, but everyone knew. That first take when Redford brushed Barbara’s hair and said goodbye without words was the one. The moment that would end the film. That night, Pollock called Arthur Lawrence. We shot the final scene today.

How did it go? Different than scripted. Lawrence felt his stomach tighten. different how Redford cut most of the dialogue. He didn’t say the big speech. Sydney, that speech is the ending. That’s Hubble’s arc, his explanation. I know, but what he did instead, Arthur, it’s better. It’s perfect. What did he do? Pollock described the moment.

The hairbrush, the wordless goodbye. As he talked, Lawrence started to understand. Sometimes writers write beautiful dialogue because they don’t trust the audience to understand silence. But Redford trusted silence. Trusted that 3 seconds of gesture could communicate more than two pages of explanation.

“Can I see it?” Lawrence asked. “Not yet, but you will.” Months later, the film premiered. The audience loved it, cried during the final scene. That moment when Hubble touches Katie’s hair became iconic. People talked about it. Critics praised it. It became one of the most memorable endings in cinema. Barbara Streryand was asked about it years later. That moment wasn’t planned.

She said, “Oh, Bob just did it and suddenly I wasn’t acting anymore. I was just Katie feeling Hubble let me go.” That’s when I knew I was working with someone who understood that film acting isn’t about saying lines. It’s about being present. Sydney Pollock reflected on it in interviews.

Redford taught me something important that day. As a director, you can write perfect dialogue, plan perfect scenes, but but sometimes you have to trust your actors to know their characters better than anyone. Bob knew Hubble wouldn’t explain himself. He knew the character would communicate through gesture, not words.

I almost didn’t let him do it. Thank God I did. Redford himself rarely discussed it, but once in a TCM interview decades later, he addressed it. Hubble was a man who chose comfort over confrontation his whole life. The ending shouldn’t suddenly make him articulate about that choice. He knew what he’d done. Katie knew. The audience knew.

Adding dialogue would have been explaining the obvious. So instead, I just tried to be present with her to acknowledge what we’d had and lost. To say goodbye the way Hubble would gently with love without explanation. The scene changed how Hollywood thought about film endings. Before the way we Were endings needed to explain everything, tie up every emotional thread, make sure the audience understood exactly what happened and why.

After that final scene, filmmakers started trusting silence more, trusting gesture, understanding that sometimes the most powerful moments happen when characters stop talking and just feel. Film schools teach that scene now. Show it to students learning about the difference between theatrical acting and film acting.

On stage, actors need words to project emotion to the back row. On film, the camera can capture everything. A touch, a look, a moment of recognition. The way we were became a classic. The love story, the Streryand song, the political backdrop, all of it worked beautifully. But the moment people remember most is the ending. That quiet, wordless goodbye on a New York street.

Two pages of dialogue replaced by three seconds of tenderness. A refusal to speak, creating the most eloquent ending imaginable. An actor trusting his instinct over the script. A director brave enough to let him try. And a moment that proved sometimes the most powerful thing you can say is nothing at all. If this story about trusting instinct over explanation moved you, make sure to subscribe and hit that thumbs up button.

Share this with someone who understands that silence can be more powerful than words. Have you ever found that not saying something communicated more than speaking? Let us know in the comments. And don’t forget to ring that notification bell for more stories about the moments that changed cinema forever.

News

Admiral Shibazaki Boasted “It Will Take 100 Years to Capture Tarawa” — US Marines Did It In 76 Hours

At 13:30 hours on November 23rd, 1943, Colonel David Shupe stood on a two-mile strip of coral called Betio,…

Japanese Troops Were Terrified When U.S. Marines Cleared Trenches Without Letting Go Of The Trigger

On the morning of August 17th, 1942, at 0917, Sergeant Clyde Thomasson crouched behind a palm tree on Makan Island,…

Japanese Soldiers Were Terrified When .50 Caliber Machine Guns Penetrated Their Concrete Bunkers

On the morning of May 14th, 1945, at 0630 hours, Corporal Lewis Ha crouched behind a coral outcrop on Okinawa’s…

General Hyakutake Ignored The “No Supplies” Warning — And Marched 3,000 Men Into The Jungle To Die

On the morning of December 23rd, 1942, at 0800 hours, Lieutenant General Harukichi Hiakutake sat in his command bunker on…

Colonel Ichiki Was Told “Wait For Reinforcements You Fool” — He Attacked Anyway And Lost 800 Men

At 3:07 in the morning on August 21st, 1942, Colonel Kona Ichiki crouched behind a fallen palm tree on the…

Japanese Soldiers Were Terrified When U.S. Marines Turned Anti-Tank Guns Into Giant Shotguns

On the morning of August 21st, 1942, at 3:07 a.m., Private First Class Frank Pomroy crouched behind a 37 millimeter…

End of content

No more pages to load