Robert Redford opened his trailer door on the set of The Sting and stopped cold. Every single inch of the floor, the walls, the furniture buried under 3 ft of popcorn, 40,000 kernels covering everything. And sitting on top of the popcorn mountain, a note in Paul Newman’s handwriting, butter or salt, PN. This wasn’t the first prank.

It wouldn’t be the last. But what Redford did in response 3 days later became the most legendary act of revenge in Hollywood history. It involved Newman’s Porsche, a chainsaw, and a prop department that should have said no, but didn’t. This is the story of the day Paul Newman and Robert Redford turned the Sting into a prank war, and how their competition made the movie better.

May 1973, Chicago. The Sting was already behind schedule. Director George Roy Hill was furious about the pranks. The studio was threatening to shut them down, but Newman and Redford couldn’t stop because for them, the pranks weren’t about being childish. They were about trust. To understand what happened in Chicago, you need to go back four years.

1969, 20th Century Fox Backlot, Butch Cassidy, and the Sundance Kid. That’s where it started. Not with popcorn, with a bicycle. Newman and Redford didn’t know each other before Butch Cassidy. Newman was already a legend. And Redford was the new guy, the pretty face from Broadway, who’d done a few forgettable films. On the first day of shooting, Newman walked up to Redford’s trailer and knocked.

Redford opened the door. Newman looked him up and down and said, “So, you’re the guy they think can replace McQueen.” It wasn’t friendly. Steve McQueen had turned down the Sundance role. Everyone knew it. Everyone knew Newman wanted McQueen. And now here was Robert Redford, goldenhaired and young, trying to fill those boots.

Redford could have been intimidated. He could have tried to win Newman over with flattery or deference. Instead, he smiled and said, “I’m the guy who’s going to make you look old.” Newman blinked. Then he started laughing. “A real laugh, not a polite one.” “Oh, this is going to be fun,” Newman said, and he walked away. The next morning, Redford arrived on set to find his bicycle missing.

“Not just any bicycle, the one he was supposed to ride in the famous Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head scene.” In its place was a tricycle. A child’s tricycle with training wheels and a little bell taped to the handlebars was a note. Thought this might be more your speed. PN. The crew held their breath. Redford stared at the tricycle for a long moment.

Then he turned to the assistant director and said, “Where’s Newman?” Newman was in his trailer, probably listening through the window. Redford walked over and knocked. When Newman opened the door, Redford was holding the tricycle over his head. “Thanks,” Redford said. My kid’s going to love this. Newman’s smile faltered. He’d expected anger or embarrassment.

He got gratitude. Redford turned to walk away. Then he stopped and looked back. By the way, Redford said, I left something in your trailer yesterday. Hope you like it. Newman’s face went pale. He rushed back inside. His entire wardrobe for the film. Hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of custom period costumes had been moved.

In their place, hanging neatly on the rack, were six identical clown suits, complete with red noses. That’s when George Roy Hill knew he had something special. Not because of the pranks, because of what the pranks revealed. Newman and Redford trusted each other enough to push back, to test boundaries, to see how far they could go.

And that trust, that willingness to mess with each other translated into the most natural onscreen chemistry Hollywood had seen in years. Butch Cassidy became a phenomenon. The film made over $100 million. Critics called Newman and Redford the new Redford and Newman. Wait, the new Bogart and Beall the new Well, there was no comparison.

They were something completely original. But here’s what nobody knew. After Butch Cassidy wrapped, Newman and Redford didn’t speak for two years. Not because they disliked each other, because they were too competitive. Newman was threatened by how much audiences loved Redford. Redford resented always being called Newman’s co-star instead of an equal.

The silence broke in 1972 when Universal offered them the sting. $500,000 each. Equal billing. George Roy Hill directing again. The pitch was simple. Butch and Sundance as conmen in 1930s Chicago. Newman read the script and called Redford. We doing this? Newman asked. Redford was quiet for a moment. Only if you promise not to go easy on me this time.

Wouldn’t dream of it, Newman said, and he meant it. The Sting began shooting in February 1973. Chicago was freezing. The period sets were elaborate and expensive. The studio was nervous because the film’s plot was complex, and they weren’t sure audiences would follow it. George Roy Hill was under immense pressure to deliver something as successful as Butch Cassidy.

And into this pressure cooker walked Newman and Redford, ready to destroy each other with pranks. The popcorn incident happened in May, 4 months into shooting. Newman had been planning it for weeks. He’d recruited the entire prop department. They’d spent three nights popping 40,000 kernels of popcorn in the studio kitchen, storing it in industrials-sized garbage bags, and smuggling it onto set and equipment cases. The execution was flawless.

Redford had a morning call time, but Newman arrived at 4:00 a.m. He picked the lock on Redford’s trailer using a bent paperclip. For the next two hours, Newman and five crew members filled the trailer. Not just sprinkled, filled. 3 ft deep, every surface. Opening a drawer released an avalanche of popcorn.

The bathroom sink was a popcorn fountain. Even the air vents were stuffed, so when Redford turned on the AC, more popcorn would blow out. The note, “Butter or salt,” was Newman’s signature move. Always leaving a calling card, always making it personal, always making it funny enough that you couldn’t get mad. Only imp

ressed. At 7:30 a.m., Redford opened his trailer door. The popcorn avalanche hit him like a wave, knocking him backward off the steps. He landed on his back in the parking lot, covered in kernels, staring up at the Chicago sky. The crew, hiding behind equipment trucks, started laughing. Redford lay there for a long moment.

Then he started laughing too. Newman, he shouted. Newman, you beautiful bastard. But inside, Redford was already planning his response. And it had to be bigger. It had to be undeniable. It had to make Newman understand that this war had no limits. 3 days later, May 15th, 1973, Robert Redford walked into the prop department.

The head of props, a man named Jerry Wonderlick, looked up from his workbench. Morning, Bob. What can I do for you? Redford smiled. It was not a friendly smile. Jerry. Redford said, “How would you like to be part of Hollywood history?” 20 minutes later, Jerry was shaking his head. Bob, I can’t. Newman will kill me. George will fire me.

The studio will sue. This is This is insane. Redford leaned against the workbench. Jerry, let me ask you something. What did you want to be when you grew up? A propmaster? Jerry said. I wanted to make movie magic. And what are you doing right now? Redford asked. Building furniture, painting walls, making things look real. Jerry nodded slowly.

But magic? Redford continued. Magic is making the impossible happen. Magic is cutting a Porsche in half. Jerry’s eyes widened. You’re serious? You actually want to cut his car in half? Redford pulled out a checkbook. I’ll pay for the replacement. I’ll take full responsibility. I’ll tell George it was all me. But Jerry, this is your chance.

Help me build something unforgettable. Jerry looked at the checkbook. He looked at Redford’s face and then he started laughing. Oh man. Oh man. Newman is going to lose his mind. He grabbed a pencil and started sketching. Okay. We’ll need a chainsaw, industrial grade. We’ll need to drain the fluids first so it doesn’t catch fire.

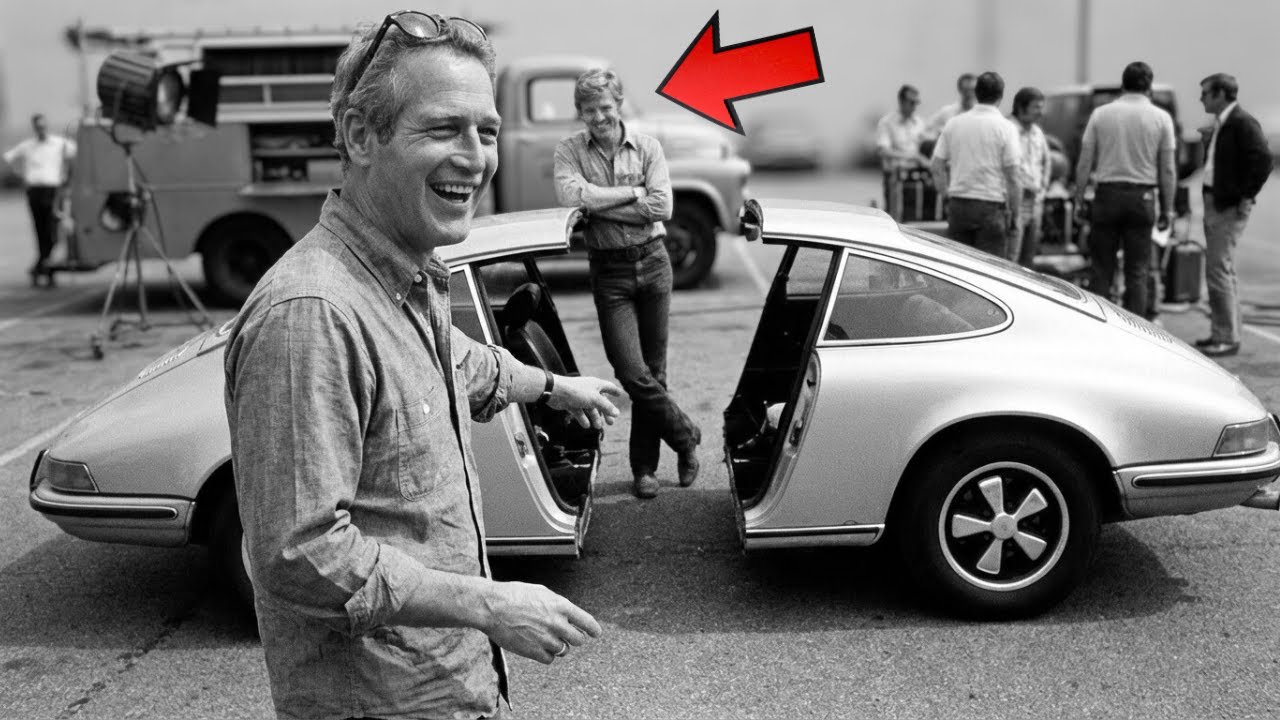

We’ll need a crane to hold it steady. We’ll need The plan was elegant in its brutality. Newman’s Porsche 911, his baby, his pride and joy, was parked in the studio lot. Redford would wait until Newman was on set for a long scene, something that would keep him occupied for at least 2 hours.

Jerry and his team would wheel the Porsche into the prop warehouse using a car dolly. They would methodically cut the car in half lengthwise right down the middle using a professional chainsaw and a plasma cutter for the metal frame. They would then reassemble each half with supports so both pieces could stand independently.

Finally, they would wheel both halves back to Newman’s parking spot, positioning them 6 ft apart so when Newman returned, he would see his car separated. The note would read, “I only needed half as much. Thought you could use the rest RR. But there was a problem. Nobody anticipated George Roy Hill. May 18th, 2 p.m.

Newman was on set filming a complex card trick scene that required dozens of takes. Perfect timing. Jerry and his crew moved Newman’s Porsche into the warehouse. Redford was there, chainsaw in hand, ready to make the first cut. Jerry had marked the center line with tape. The prop crew had cameras ready to document everything.

This was going to be legendary. The warehouse door opened. George Roy Hill stood silhouetted in the doorway. “What?” he said slowly. “In the name of God, are you doing?” Jerry dropped his wrench. Redford turned off the chainsaw. Nobody moved. George walked into the warehouse, looked at the Porsche, looked at the chainsaw, looked at Redford.

“You’re cutting his car in half.” “It wasn’t a question.” “Yes,” Redford said. George nodded slowly. Then he pulled up a chair and sat down. Okay, just one question. You’re paying for the replacement? Redford nodded. George leaned back in the chair. Then don’t let me stop you. This I have to see.

The next hour was one of the most surreal experiences in Hollywood history. A director, an Academy Award nominated actor, and a prop crew, all standing in a warehouse taking turns cutting a Porsche 911 in half with industrial power tools. George supervised the cuts to make sure they were straight. If you’re going to ruin a man’s car, George said, “At least ruin it professionally.

By 400 p.m., the Porsche existed as two separate halves. By 4:30, both halves were back in Newman’s parking spot.” The note was taped to the driver’s side half. The entire cast and crew had been quietly informed. Everyone found a reason to be near the parking lot when Newman’s scene wrapped. At 5:15, Paul Newman walked out of the sound stage exhausted from 50 takes of the card trick.

He was thinking about going home, having a beer, and calling his wife. He walked toward his parking spot. He saw his Porsche. He stopped walking. His brain couldn’t process what his eyes were seeing. The car was there, but it was also not there. It was two things, two half things. He walked closer. He saw the note. He read it.

Then he started laughing. Not a normal laugh. A slightly unhinged laugh. The laugh of a man who has been beaten at his own game and knows it. He turned around. The entire cast and crew were watching from a distance. Redford was leaning against a lighting truck, arms crossed, smiling. Newman pointed at him.

“You,” Newman said. “You are the most magnificent son of a I have ever met.” Redford walked over. I learned from the best. Newman looked at the two halves of his Porsche. How did you even Jerry? Jerry helped you. Jerry waved nervously from behind a camera cart. Newman waved back. Then he turned to Redford. This is war.

You understand that? This is actual war now. Redford nodded. I wouldn’t have it any other way. George Roy Hill stepped forward. Gentlemen, I need to tell you something. For the past four months, I’ve been furious about your pranks, the delays, the distractions, the insurance claims. Newman and Redford looked down like scolded children.

But I was wrong, George continued. Both actors looked up in surprise. Your competition, this constant oneupmanship, it’s making you better. Every scene you two do together has this energy, this spark. You’re trying to outact each other the way you’re trying to outrank each other. And it’s brilliant. The footage we’re getting is better than Butch Cassidy.

So, here’s my new rule. Prank each other all you want. Just do it after we finish shooting for the day. Newman grinned. Redford grinned. This was permission. This was license to escalate. Over the next 6 weeks, the sting became a battlefield. Newman filled Redford’s hotel room with 2,000 balloons. Redford replaced all of Newman’s dialogue in the script with lines from nursery rhymes.

Newman hired a mariachi band to follow Redford around the set for an entire day. Redford had Newman’s trailer moved three miles away to a grocery store parking lot. Newman paid the Chicago Police Department to give Redford a fake speeding ticket for $10,000. Redford replaced every photo in Newman’s wallet with pictures of himself.

The studio executives were horrified. The insurance company threatened to drop coverage, but George Roy Hill protected them because he saw what nobody else could see. The pranks weren’t destroying the film. They were creating it. In the movie, Newman and Redford play con artists who must trust each other completely while pretending to betray each other constantly.

That dynamic, that tension between genuine partnership and performative conflict had to feel real. And it did feel real because off camera, Newman and Redford were living it. They trusted each other enough to risk genuine anger. They competed hard enough to push each other to excellence, and the camera captured all of it.

The sting wrapped in June 1973. The final prank came on the last day of shooting. Newman and Redford had a bet about who could pull off the most expensive prank. Redford had spent $30,000 replacing Newman’s Porsche. Newman needed to beat that. On the final day, Newman gave Redford a gift, a wrapped box. Redford opened it carefully, expecting something terrible.

Inside was a gold Rolex, a real one. engraved on the back to the second best prankster in Hollywood. PN Redford was speechless. This was genuine from Newman. He looked up. Newman was smiling. Check the parking lot, Newman said. Redford walked outside. His car was gone. In its place was a billboard 50t tall, 40 ft wide. A photo of Redford’s face and text that read, “Available for children’s parties.

Call Redford’s personal phone number.” The billboard stayed up for 6 months. Redford’s phone rang constantly. Desperate parents booking clowns, reporters investigating, pranksters pranking the prankster. Newman’s final prank cost him $75,000. The billboard rental. The photo rights. The legal fees when Redford tried to take it down.

Redford called Newman the day he saw the billboard. “You win,” Redford said. “I can’t beat this. You win.” “I know,” Newman said. “But let’s be honest. You made me work for it. The Sting premiered in December 1973. It was a phenomenon, $160 million at the box office. Seven Academy Awards, including best picture.

Critics praised the chemistry between Newman and Redford. One reviewer wrote, “You can’t fake the kind of trust these two actors have. You can see it in every glance, every reaction, every moment they share the screen.” They were right. You can’t fake that trust. But you can earn it by cutting a man’s Porsche in half.

By filling his trailer with popcorn, by competing so hard that you bring out the best in each other. That’s what Newman and Redford understood. The pranks weren’t about being childish or difficult. They were about establishing that their relationship could withstand anything. That they could push each other to the edge and still trust the other person would be there.

Years later, in 1998, Robert Redford was asked about the prank war during the Sting. He smiled and said, “Paul taught me that if you can’t mess with someone, you can’t trust them because if you’re afraid of their reaction, you’re not really friends. You’re just polite strangers.” Paul Newman died in 2008. At his memorial service, Redford stood at the podium and told the Porsche story.

The congregation laughed. Then, Redford said something that made them cry. Paul once told me that competition is just another word for respect. You only compete with people you think can beat you. You only prank people you trust to understand. I spent 40 years competing with Paul Newman.

And every single day he made me better. Not just as an actor, as a person. After the service, Redford walked to his car. Taped to the windshield was a note in Newman’s handwriting. It had been placed there by Newman’s wife, Joanne, per Paul’s final instructions. The note read, “One last thing. Your car is not really there. It’s in a parking lot in Chicago.

Hope you packed comfortable shoes.” PN Redford stood in the parking lot holding the note, laughing and crying at the same time. Because even in death, Paul Newman had won the prank war. But that’s the beautiful part. In their competition, nobody really lost because what they built together, that trust and chemistry and willingness to push each other beyond limits became the thing audiences remembered.

Not the awards, not the box office numbers, the friendship, the real messy, competitive, beautiful friendship between two men who made each other better by refusing to let the other one settle. If this story of legendary friendship and competition moved you, share it with someone who needs to remember that the best relationships are the ones that challenge you.

Have you ever had a friendship that made you better by pushing you harder? Let us know in the comments. And don’t forget to hit that notification bell for more untold stories from Hollywood’s golden

News

Waiter praised Redford for WRONG MOVIE at Grand Hotel — his response was warmed hearth

Jean Mark had been working at the Gran Hotel daper for six years. He’d served princes, presidents, and movie stars….

“Jeremiah Johnson” crew STRANDED at 11,000 feet — what Redford did next SAVED their lives

Sydney Pollock was screaming into a dead radio. We need helicopters now. We have 40 people freezing to death up…

Sydney Pollack FIRED Redford mid-scene — Redford’s response STUNNED the entire crew

Get off my set. The words hung in the air like a gunshot. Sydney Pollock, one of Hollywood’s most respected…

“Stunt explosion went WRONG on set — Redford’s 3-second decision saved a man’s LIFE”

The explosion was supposed to go off at 3:47 p.m. It went off at 3:46. 1 second early doesn’t sound…

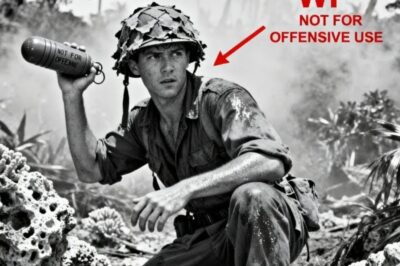

How One Engineer’s “Stupid” Idea Turned U.S. Paratroopers Into Tank Killers

Aberdine Proving Ground, Maryland. May 12th, 1942. The morning mist hung over the test range as five different anti-tank weapons…

Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day

May 18th, 1944. Biak Island, Dutch New Guinea. Private First Class. Harold Moon crouches behind a shattered palm tree as…

End of content

No more pages to load