In May 1945, the war ended, but thousands of German tanks were still scattered across Europe. Panthers, Tigers, and Panzer IVs sat abandoned on roads, in forests, and outside ruined factories. The Allies now faced a practical question: what would happen to Hitler’s armored fleet? When Germany surrendered on 8 May 1945, its armored force was a shadow of what it had been earlier in the war.

Months of fuel shortages, factory bombing, and constant retreat had left hundreds of vehicles scattered across the country. In the Ruhr, in Bavaria, and around Berlin, Allied soldiers found Panthers and Panzer IVs abandoned, often with empty fuel tanks or missing parts taken to keep other vehicles running. Many tanks had been immobilized deliberately as German crews destroyed engines or gearboxes before surrender.

Allied forces quickly secured the tanks left behind. In the American zone, US Technical Intelligence teams catalogued vehicles at sites such as Oberursel and Gaildorf. British REME units did the same at Hillersleben and Sennelager, while Soviet trophy brigades recovered armor across Silesia and into Berlin.

The condition of Germany’s surviving tanks varied. Some were almost intact but mechanically unreliable from worn components. Others had been stripped of radios, optics, or engines, leaving only shells. Prototypes and factory-fresh hulls often lacked complete systems because production had been disrupted by bombing and shortages.

Operational records found in workshops helped Allied teams trace wartime deployment, although many documents had been burned in the final weeks.. By the summer of 1945, most of Germany’s armored fleet sat in Allied-controlled yards, awaiting decisions on whether they would be studied, transferred, or destroyed. As the Allies organized occupation zones in mid-1945, attention shifted from collection to technical evaluation.

The United States and Britain wanted to understand how German tanks were designed, why they performed well in combat, and where their weaknesses lay. This meant shipping selected vehicles overseas or testing them at proving grounds across Europe. For the United States, the center of this effort became Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. Beginning in late 1945, the U.S.

Army shipped examples of the Panther, Tiger I, Tiger II, Jagdpanther, and several assault guns to the facility. Engineers conducted gunnery tests, mechanical trials, and armor-penetration studies. Results highlighted a clear pattern: excellent firepower and optics, but chronic failures in final drives and gearboxes. The British carried out similar studies, though most testing occurred inside Germany.

British engineers compared the Panther’s sloped armor and long-barreled gun with the Sherman and Churchill designs. They noted that German optics were of very high quality. At the same time, maintenance crews recorded how difficult it was to service German vehicles under field conditions.

British evaluations influenced early Cold War thinking but did not lead directly to domestic production of German-style tanks. The Soviet Union approached the issue differently. Trophy brigades collected large numbers of Panzer IVs, Panthers, and StuGs primarily for training purposes. Test results confirmed Soviet wartime observations: strong frontal armor and high-velocity guns, but mechanical systems that wore out quickly under harsh conditions.

By the early 1950s, most captured German tanks in Soviet hands had been scrapped once spare parts ran out. Some of the most important discoveries came from former research sites. At Kummersdorf and Hillersleben, Allied teams found incomplete hulls and experimental vehicles, including elements of the Maus program and parts of the planned E-series.

At Haustenbeck, workshops held damaged Jagdtigers, Panthers awaiting repair, and crates of spare parts, evidence of late-war engineering that never reached full production. Early occupation directives required all German armored vehicles to be reported, secured, and restricted from unauthorized use. This triggered a debate among Allied planners: should the tanks be preserved for study, transferred to other nations, or destroyed to prevent future militarization? Each power pursued different goals.

The United States prioritized testing, the Soviets gathered large stocks before deciding their fate, and Britain, limited by manpower and shipping, evaluated fewer tanks on-site. Across all Allied reports, conclusions were similar: German tanks paired advanced optics and powerful guns with maintenance-heavy designs.

These mixed results shaped early Cold War development, encouraging interest in sloped armor and improved optics while highlighting the need for simplicity and reliability. After testing ended, the Allies still held thousands of tons of armored vehicles, spare parts, and unfinished prototypes.

Between 1946 and 1948, the Allied Control Council issued a series of directives ordering the systematic destruction of German military equipment. Tanks, armored hulls, and vehicle components were classified as prohibited materials, meaning they could not remain in German hands or be used for any future rearmament. As a result, widespread demilitarization began across the former Reich.

Industrial centers in the Ruhr, Saxony, and Thuringia became focal points for scrapping. Steel plants in Bochum, Essen, and Magdeburg received long lines of armored hulls, many delivered by rail from nearby depots. Workers cut Panthers, Panzer IVs, and StuGs into pieces using torches and heavy machinery. Germany’s postwar steel shortage made this recycling effort important for reconstruction, and the recovered metal went directly into rebuilding bridges, factories, and housing.

By late 1947, hundreds of armored vehicles had been melted down, leaving little trace of their wartime role. Not all tanks went to factories. In many rural areas, Allied engineers used abandoned German armor as part of environmental or engineering projects. One well-documented example occurred along the Enns River in Austria, where bulldozed Panthers and other vehicles were pushed into embankments to stabilize riverbanks.

Similar practices occurred in quarry sites across central Europe, where tanks served as fill for landslide-prone areas. Over time, soil and vegetation covered these remains, making them part of the landscape. Another significant share of surviving German armor became target hulks. The British used tanks at ranges like Lulworth, the Americans at Grafenwöhr and Aberdeen, and the Soviets at various training sites.

These vehicles allowed crews to test new ammunition types, practice gunnery, and evaluate the effectiveness of emerging technologies. Once heavily damaged, they were either left in place or broken down for scrap. Clearance operations continued in battle-scarred regions where vehicles had been abandoned during the final months of the war.

Czechoslovak and Polish teams removed wrecks from roadsides, forests, and former defensive lines, sending them to scrap yards or using them in land-reclamation projects. Former research sites also saw extensive destruction. Incomplete prototypes such as components of the Maus program, E-series hulls, and experimental chassis were dismantled.

The scale of demilitarization left few German tanks intact. Myths sometimes circulate about secret storage bunkers filled with Panthers or hidden warehouses containing undamaged Tigers, but available evidence points to misidentified structures or Cold War rumors. Most of Germany’s wartime armored vehicles were destroyed by 1948, leaving only the handful preserved for testing or transferred to foreign armies.

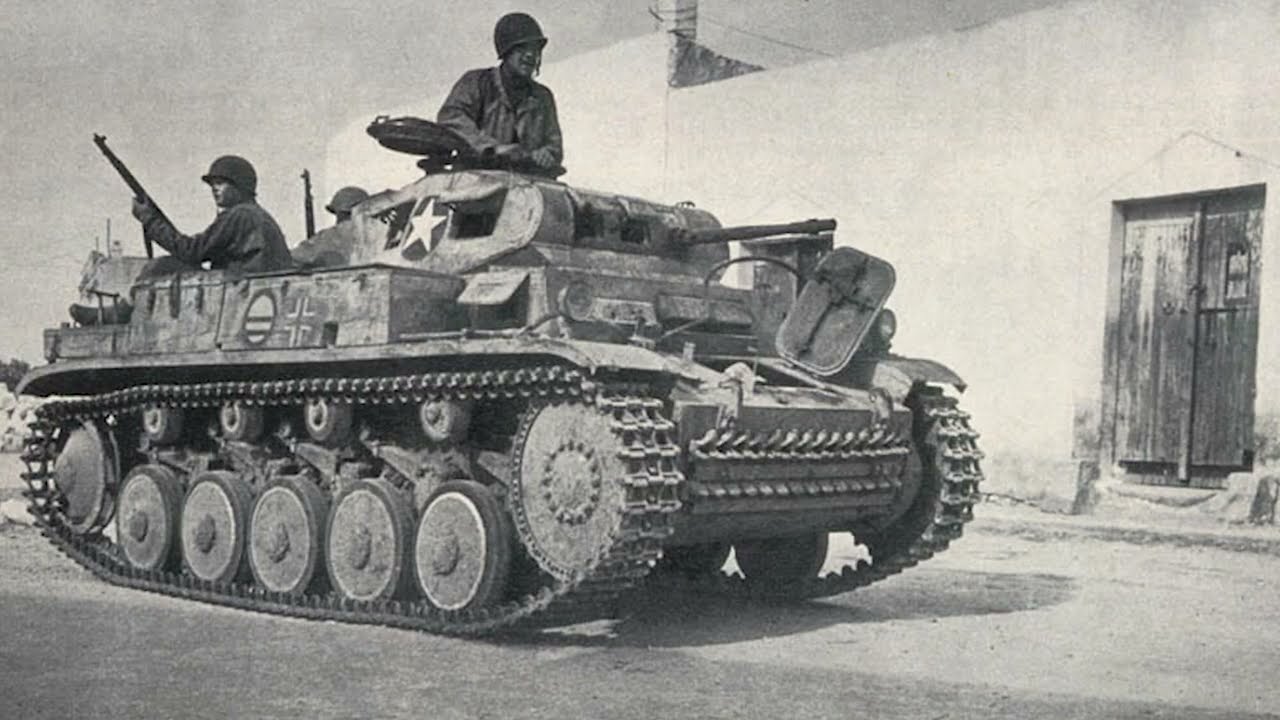

The German tank fleet that had once dominated European battlefields had been dismantled piece by piece. While most German tanks were destroyed or recycled, a smaller but significant number found new life in foreign armies rebuilding after the war. These vehicles filled gaps for nations that lacked modern armor or needed equipment quickly.

Their postwar service created unexpected legacies, stretching the operational life of German designs into the 1950s and, in some cases, even the 1960s. France was among the earliest and heaviest users. French forces collected Panthers from depots in southwest Germany and incorporated them into the 503rd Combat Tank Regiment. Crews admired the Panther’s firepower and optics, which surpassed many Allied tanks of the period.

But maintenance challenges quickly appeared. With limited spare parts and worn-out drivetrains, French workshops often cannibalized multiple vehicles to keep one running. Reports from the early 1950s described frequent transmission issues, and by 1951, France retired the last Panthers due to escalating maintenance costs.

Even so, these tanks influenced French armored doctrine at a time when the country was reestablishing its military capabilities. Czechoslovakia played a unique role because it had been a major manufacturing center for German armor during the war. After 1945, Czechoslovak factories continued building the Hetzer (G-13) based on the Panzer 38(t) chassis. Many of these were sold to Switzerland, which operated them well into the Cold War.

The combination of simple mechanics and reliable engines made the Hetzer suitable for nations seeking cost-effective tank destroyers. Czechoslovakia also used leftover Panzer IVs and StuGs before gradually replacing them with Soviet designs. In Eastern Europe, countries such as Romania, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia received German vehicles either from wartime captures or Allied redistribution.

Romania operated several Panzer IVs for training, while Bulgaria integrated a mix of Panzer IVs and StuGs into its early postwar armored units. By the mid-1950s, most Eastern European users had shifted fully to Soviet-supplied T-34s and newer armored vehicles. Spain also became a modest but important postwar user of German armor. In late 1943, Germany supplied Franco’s government with 20 Panzer IVs and 10 StuG assault guns.

The Panzer IV remained Spain’s premier vehicle into the mid-1950s, operating alongside older Panzer 1s. As maintenance grew difficult, the fleet shrank, and in 1967 Spain sold seventeen surviving Panzer IVs to Syria. One of the most unexpected postwar users was Syria.

During the 1950s and 1960s Syria acquired a number of Panzer IVs from Czechoslovakia and Spain, placing them in frontline units along the Golan Heights. These tanks remained in service into the 1970s, marking one of the last known operational uses of a German WWII tank. Their presence reflects the global circulation of surplus armor in the early Cold War period, as nations sought affordable equipment amid emerging regional tensions.

Spare-parts scarcity shaped the fate of these fleets. Nations relied on captured depots, local manufacturing, or improvised solutions. Mechanics often fabricated components or combined parts from multiple vehicles, while missing manuals made training difficult. Even so, the tanks influenced early Cold War doctrine.

By the mid-1950s, most countries had retired their German vehicles. Larger armies moved toward standardized equipment supplied through the United States or the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, surviving Panthers, Tigers, and Panzer IVs entered museum collections or became monuments.

Institutions such as the Tank Museum at Bovington, the Musée des Blindés in Saumur, and the Kubinka Tank Museum near Moscow preserved key examples, ensuring that these vehicles did not vanish entirely. If you found this video insightful, watch What Happened to German U-Boats After WW2? next, a deep look at how the U-boat fleet was captured, studied, and scattered across the world in the aftermath of the war.

Like this video, subscribe, and hit the bell for more History Inside. Thanks for watching.

News

How One Engineer’s “Stupid” Idea Turned U.S. Paratroopers Into Tank Killers

Aberdine Proving Ground, Maryland. May 12th, 1942. The morning mist hung over the test range as five different anti-tank weapons…

Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day

May 18th, 1944. Biak Island, Dutch New Guinea. Private First Class. Harold Moon crouches behind a shattered palm tree as…

When 5 German Panthers Attacked — This Sherman Gunner’s 5 Shots Destroyed Them All

At 1427 on June 14th, 1944, Sergeant Gordon Harris crouched inside his Sherman Firefly at the eastern edge of Lingra’s…

They Told Him to RETREAT— He Stayed and Killed 41 Japanese

At 2:17 p.m. on December 23rd, 1943, Private First Class Thomas Tommy Briggs crouched behind a shattered palm tree on…

How a U.S. Sniper’s “Outlawed” Ghillie Upgrade Made 19 Mortar Teams Vanish in the Italian Campaign

January 23rd, 1944. Monte Casino, Italy. Staff Sergeant Dalton Brennan lay perfectly still, his body pressed against cold stone. The…

What Happened to the Luftwaffe Planes After WW2?

May 1945. The war ends, and the Luftwaffe collapses overnight. Across Europe, thousands of German aircraft sit abandoned, from…

End of content

No more pages to load