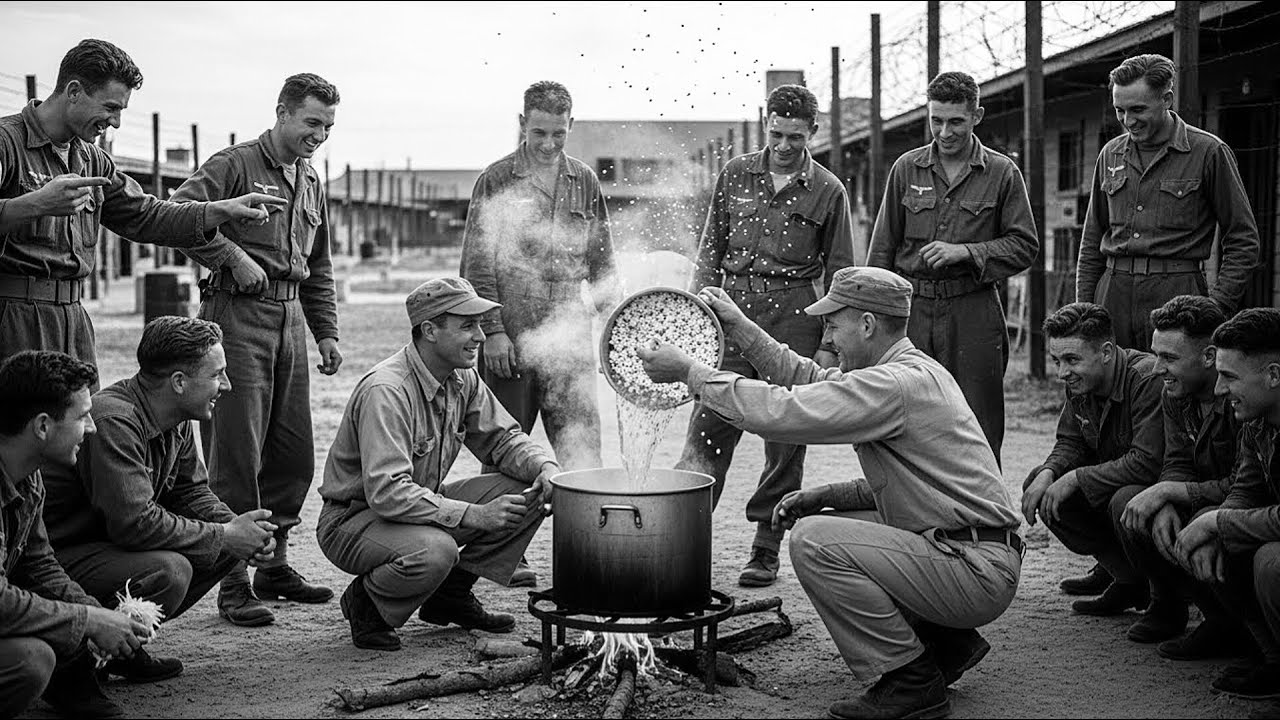

Summer 1944, Camp Herm, Texas. The war in Europe raged on, but here in the heart of America, something quieter and far more disarming was unfolding. A group of Africa corpse veterans, captured in Tunisia, and shipped across the Atlantic, had grown accustomed to the routines of captivity. Work in the cotton fields, Red Cross parcels from home, the occasional movie night in the messaul.

They prided themselves on their discipline, their European sophistication. Then one evening, the Americans decided to share a little piece of home. Guards hauled out a big pot, poured in yellow kernels, added oil, and shook it over the flames. Pop, pop, pop, pop. The sound echoed like distant gunfire, but softer, playful. The Germans watched, then burst into laughter.

“What is this madness?” one called out in accented English. “The Americans feed birds like this back home,” another mimicked, throwing handfuls into the air. Popcorn for children and chickens. They doubled over, slapping knees, the mockery rolling through the compound like a wave. Little did they know, this simple snack, dismissed as childish nonsense, would soon crack open something deeper.

A crack in the wall of propaganda, a taste of American abundance that no lecture or film could match. Over 425,000 Axis prisoners, mostly German, passed through American soil during World War II. Treated under strict Geneva Convention rules, they received the same food rations as US troops. Hearty meals of meat, vegetables, milk, bread.

Many gained weight after years of vermarked shortages. But it wasn’t just calories that surprised them. It was the casual plenty. The little luxuries taken for granted. Chocolate bars in the PX, Coca-Cola for a nickel, ice cream on hot days. Propaganda back home had painted America as decadent and weak, a mongrel nation of jazz and Jews.

Yet here were guards sharing extras, laughing easily, treating enemies with decency. Popcorn fit right into that picture. Cheap, fun, messy, utterly unger in its frivolity. Historical accounts from former powers, including letters and post-war interviews compiled in works like Arnold Kmer’s Nazi prisoners of war in America.

In camps across the South and Midwest, popcorn appeared at recreational events, movie nights, or just as a guard’s treat. The Germans saw the colonels, small, hard, unremarkable, and scoffed. “This is animal feed,” one officer reportedly said at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. “In Germany, we boil corn for pigs.

” They compared it to maze fed to livestock back home, never imagining the transformation. Europeans knew corn as palenta or foder. The American habit of exploding it into fluffy white clouds was alien, almost comical. The first tastes changed everything. The crunch, the buttery salt, the way it melted on the tongue, light, addictive, impossible to stop at one.

Carl froze midchw, then grabbed another handful. “My god,” he muttered. This is good. Laughter turned inward. Men who had sneered now reached eagerly, butter smearing chins, smiles breaking through dust caked faces. In one documented incident at a Texas camp, a group of prisoners started a friendly competition.

Who could catch the most tossed kernels in their mouths. Guards joined in, the language barrier dissolving in shared grins. What began as ridicule became delight. Popcorn wasn’t just food. It was play. It was Saturday matineese, family nights, carefree moments the war had stolen from everyone. According to P diaries and oral histories, these small encounters chipped away at Nazi indoctrination.

A man who had fought in the desert, convinced of Aryan superiority, found himself laughing like a boy over exploding corn. Another wrote home about the crazy American snack that tastes better than cake. The abundance, no rationing here, no hunger, spoke louder than any anti-American lecture. Red Cross reports noted improved morale, fewer escape attempts, even friendships forming across the wire.

Popcorn nights became a ritual in some camps, a symbol of the strange hospitality that left many Germans questioning everything they’d been told. But this wasn’t isolated whimsy. It reflected a broader truth. America’s wartime prosperity, even amid rationing at home, allowed treats for prisoners that Germans back home could only dream of.

While families in Berlin scraped by on turnip soup, their sons in Texas gained weight on steak, eggs, and yes, popcorn. The laughter that started bitter, ended warm, one prisoner later recalled, “We mocked it because we didn’t understand it. Then we tasted freedom in a handful of corn. What followed were more surprises.

ice cream socials, baseball games, holiday feasts that turned enemies into quiet admirers. The popcorn moment was small, but it planted seeds of doubt in the myth of American weakness. In the end, a simple snack did what bombs couldn’t always do. It humanized the other side. This was the quiet power of plenty. A kernel of corn popped in American oil became a bridge across the war.

The popcorn knights didn’t stop at one evening. What started as a guard’s casual gesture became a small ritual in Camp Hearn and dozens of other camps across the American South and Midwest. On movie nights, when Hollywood films flickered on a white sheet hung between barracks, the Americans brought extra bowls. Guards passed them down the rows, saying simply, “Try some more.

” The Germans, once so quick to mock, now accepted them eagerly. Hands reached out, fingers brushed in the dim light, and the old barriers of uniform and nationality softened just a little. Historical records from the US Provos Marshall General’s office and P letters home show how these moments accumulated. A sergeant from the 90th Infantry Division, who had guarded the camp later wrote in his memoir, “They laughed at first, sure, called it American bird food, but after the second or third handful, you could see it hit them. This

wasn’t just food. It was fun. something we hadn’t had much of since the war started. In one documented case at Camp McCain, Mississippi, a group of Luftvafa pilots organized their own popcorn abend after lights out, sharing stories of home while passing a single bowl around in the dark.

They even tried seasoning it with spices smuggled from Red Cross parcels, a pinch of paprika, a bit of carowway. The result, laughter when it tasted terrible, but still they ate every kernel. The shift went deeper than taste buds. Popcorn embodied the casual abundance that Nazi propaganda had ridiculed as weakness. Back in Germany, bread was rationed to 200 grams a day in many cities by 1944.

Butter was a memory. Yet here, prisoners received three full meals plus extras like this snack that cost pennies. One former P interviewed decades later for a German documentary said plainly, “We were told Americans were soft, materialistic, without culture. Then we tasted their childish popcorn and realized they could afford to be playful because they were winning. We could not.

Friendships formed in those small exchanges. A guard named Tommy from Oklahoma taught a group of Bavarians how to string popcorn for Christmas decorations, something the Germans had never seen. In return, they showed him how to carve small wooden figures with pocket knives. These weren’t grand acts of reconciliation. They were human moments.

Escape attempts dropped in camps where such interactions were common. Morale improved. Red Cross inspectors noted fewer disciplinary incidents after recreational events that included American treats. By late 1944 and into 1945, as the European War turned decisively against Germany, many prisoners began to privately admit the obvious, and America’s strength wasn’t just in tanks and planes.

It was in the everyday plenty that let them share popcorn with enemies. One officer wrote in a censored letter home. Do not believe everything you hear on the radio. The Americans are not decadent. They are generous even to us. The popcorn didn’t end the war. It didn’t erase the battles or the losses. But in those quiet Texas nights, a simple snack did something remarkable.

It reminded hardened soldiers that the other side was made of people, too. People who laughed, who shared, who found joy in something as small as exploding corn. And in that shared laughter,

News

Why The Viet Cong Fighters Feared The Australian Diggers More Than US Forces

Avoid Australian patrols, they said. They are too quiet. They appear behind you. These weren’t American assessments. These weren’t political…

100s Betrayed and Killed by Nazi Gestapo Agent – Executed: Rinnan

At dawn on April 9th, 1940, darkness fell over northern Europe. Operation Werubong officially began. Nazi German forces simultaneously invaded…

Japanese Mothers Cried When American Soldiers Gave Them Soap

August 30th, 1945 at Sugi Airfield, Kanagawa Prefecture. The sky over central Japan is a pale hazy blue. At 6:00…

“The Screams Never Stopped” — Why US Medics Were Terrified to Treat Wounded Australian SAS

Long Bin, 1969. 3:00 in the morning. An American medic watches a man walk into his surgical tent with shrapnel…

“Don’t Ask What Happened to the Prisoners” — A US Green Berets on Cooperating with Australian SAS

The phrase wasn’t shouted. It wasn’t written down. It wasn’t even delivered like an order. It came quietly, almost casually,…

The American POW Who Hunted His Torturer After the War – A Nigtmare That Never Ended

In May 1943, a B-24 Liberator bomber disappeared over the vast Pacific Ocean during a search and rescue mission. The…

End of content

No more pages to load