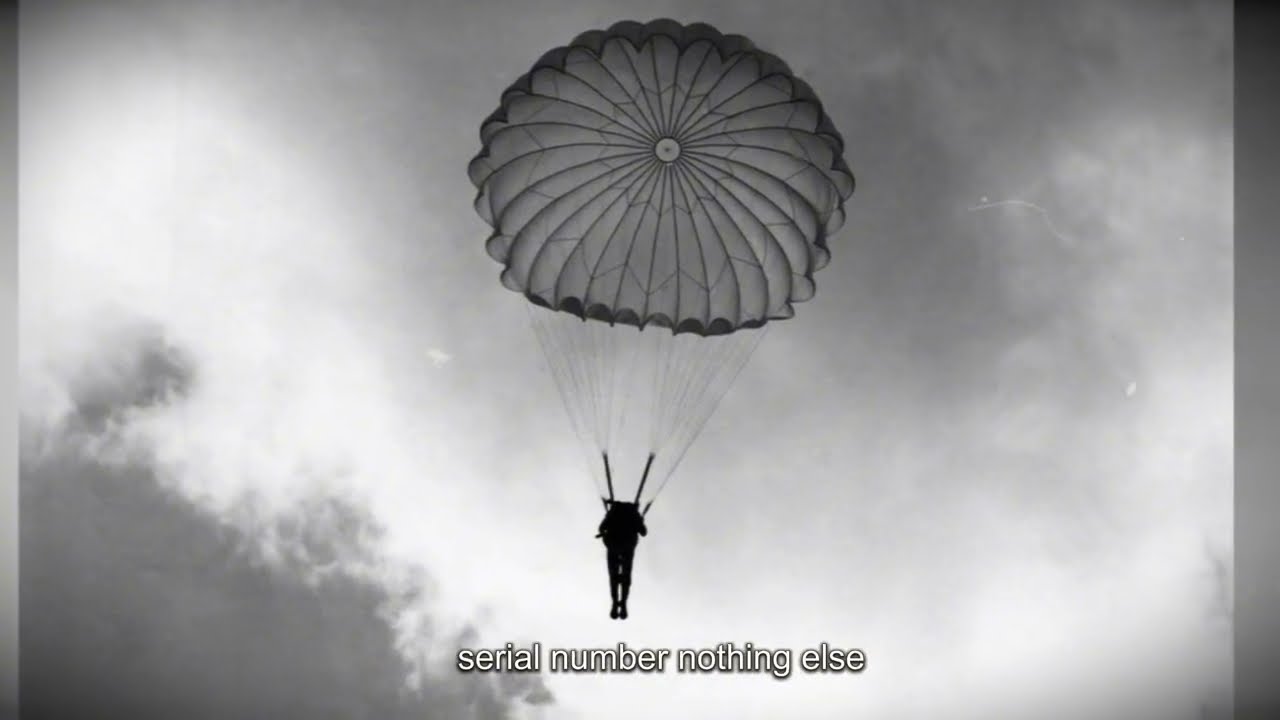

At 10:15 a.m. on March 31st, 1944, Second Lieutenant Owen John Bagot hangs suspended in his parachute harness at 15,000 ft above the Burmese jungle, bleeding from shrapnel wounds, watching a Mitsubishi A6M0 fighter circle back toward him with its guns trained on his chest. 23 years old, seven combat missions over Burma.

Three Japanese Zeros orbit the debris field where his B24 Liberator exploded 6 minutes ago. 12 American airmen scattered across three miles of sky, dangling beneath white silk canopies. The Zeros are hunting them one by one. This airspace belongs to Japan. The Burma campaign grinds through its bloodiest phase.

Allied forces lose an average of 43 aircraft per week over this theater. The Japanese Air Force shoots down parachuting air crew as standard practice. No war crime tribunals exist yet. No Geneva Convention enforcement in the China Burma India Theater. The jungle below holds no rescue teams, no friendly forces, nothing but 200 m of mountain ridges controlled by Japanese infantry.

Owen Baggot grew up in Graham, Texas. His father ran a dry goods store on Oak Street. Owen pumped gas at a Magnolia station before the war, 70 cents an hour, saved enough to take flying lessons at the Graham Municipal Airport. He enlisted in the Army Air Forces 3 weeks after Pearl Harbor. Trained at Ellington Field near Houston, washed out of fighter pilot training because his eyesight tested one line below requirement.

They assigned him to bombers instead. He wanted to hunt Japanese fighters in AP40 Warhawk. Now he gets his chance. Armed with a Colt M1911A1 pistol and no airplane, the strategic situation offers zero hope. The 10th Air Force operates from primitive air strips carved from Indian tea plantations. Supply lines stretch 7,000 mi from the United States.

Spare parts arrive by sea to Kolkata, then by rail to Assam, then by truck over the Himalayas, if the trucks survive the drive. The Japanese control Burma’s airspace with four fighter groups, approximately 140 aircraft, veteran pilots who cut their teeth over China. They shoot down everything that flies. Owen’s bomber carried 10 men this morning. Five officers, five enlisted.

Their mission targeted the railway bridge at Mandandalay, part of the Japanese supply line feeding troops into India. They never reached the target. The Zeros intercepted them 40 mi out, attacked from the sun, cannon shells ripping through aluminum skin like paper. The number three engine caught fire first, then number two.

The pilot gave the bailout order at 10,000 ft. Owen jumped from the waist gunner position, pulled his rip cord, floated into hell. The lead zero makes its first gun pass at Staff Sergeant Harold Thompson, the tail gunner. Thompson dangles 400 yd to Owen’s left. The Zero approaches from behind, closes to 100 ft, opens fire with its twin 7.7 mm machine guns.

Tracers stitch through Thompson’s parachute canopy. The silk shreds. Thompson accelerates downward, spinning, screaming. 11,000 ft to impact. The Zero pulls up, banks right, selects its next target. Owen checks his wounds. Shrapnel penetrated his left thigh during the bomber’s death spiral before he jumped.

Blood soaks through his flight suit, warm and sticky. His right hand clutches the parachute risers. His left hand moves to his hip holster, finds the pistol grip, leaves it holstered. Not yet. The Zero climbs back to altitude, positioning for another pass. The Mitsubishi A6M0 carries an operational ceiling of 33,000 ft. Maximum speed 332 mph, range, 1900 m.

Two 20 mm cannons in the wings. Two 7.7 mm machine guns in the nose. Armor protection, none. Pilot protection, none. The zero trades defense for maneuverability. Turns tighter than any allied fighter. Climbs faster. Fights longer, but it burns when hit. The fuel tanks lack self-sealing protection.

One good burst sets them ablaze. Owen knows this. Every briefing hammers it home. Zeros burn easy. Aim for the tanks. Aim for the engine. But those briefings assumed he would be firing from a bombers’s gun turret or a fighter’s wing guns, not a pistol, while falling through space. The temperature at 15,000 ft measures 12° F.

Owen’s leather flight jacket provides minimal insulation. His breath forms ice crystals. His hands stiffen. The shrapnel wound throbs with each heartbeat. Blood loss makes him dizzy. The jungle below looks like green carpet, distant and indifferent. The second zero attacks Lieutenant James Miller, the co-pilot.

Miller drifts 800 yd ahead, descending faster because his parachute took damage during deployment. The Zero approaches head-on this time, firing from 300 yd out. The angle is wrong. Most rounds miss. Two rounds punch through Miller’s chest. His body goes limp in the harness, still descending, already dead.

The zero doesn’t verify. It knows. Owen counts the enemy. Three zeros. Nine American parachutes still in the air. Now eight. Simple mathematics. The zeros will kill everyone unless something changes. His M1911 holds seven rounds in the magazine, one in the chamber, eight shots total. Effective range against a human target, 50 yards.

Effective range against an aircraft, zero. The Army Air Forces issued him this pistol for survival on the ground, for signaling rescuers, for defending against wild animals. Nobody mentioned aerial combat. If you want to see how Owen Bagot’s desperate situation turned out, please hit that like button.

It helps us share more forgotten stories like this one. Please subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to Owen. Owen makes a decision that defies every survival instinct. He goes limp in his harness. His head drops forward onto his chest. His arms dangle loose. His legs hang motionless. He becomes a corpse, pre-killed, not worth the ammunition.

The shrapnel wound makes it convincing. Blood drips from his flight suit, visible against the white parachute silk. He looks like the others. He looks dead. The zero closes to 75 yards. The pilot checks his gun sight, finger on the trigger. Then he hesitates. The American appears lifeless already. The parachute shows no oscillation, no steering inputs.

Maybe another zero already hit this one. Maybe the bomber explosion killed him. The pilot decides to verify visually before wasting rounds. He throttles back further, reduces speed to 95 mph, just above stall speed. He slides his canopy open for better visibility. The slipstream roars past his cockpit. He banks gently left, pulling alongside the parachute, offset by 30 ft.

He wants to see the American’s face. Confirm the kill. Move on. Owen times it perfectly. He lifts his head slowly, moving only his neck. His right hand reaches across his body to the holster on his left hip. The Zero drifts into position, close enough to see the pilot’s leather flight cap, his goggles, the expression of mild curiosity on his face.

Owen draws the M1911A1 in one smooth motion. The pistol weighs 2 lb 7 oz. Barrel length 5 in. Muzzle velocity 830 ft/s. Caliber45 ACP. Seven rounds in the magazine, one chambered, safety off because he thumbmed it down during the draw. The Japanese pilot sees the movement. His eyes widen. His hand reaches for the throttle, pushes it forward.

The zero begins to accelerate. Too slow, too late. Owen extends his arm straight out. No time to aim properly. No way to achieve a proper shooting stance while hanging in a parachute harness. He points the pistol at the cockpit, compensates for wind drift, leads the target by instinct. The Zero fills his vision 30 ft away, close enough to smell the engine exhaust, close enough to see the red meatball insignia on the fuselage.

He fires. The first shot punches through the Zero’s open canopy, misses the pilot’s head by inches, exits through the opposite side. The pilot flinches, banks hard right. Owen tracks the movement, fires again. The second shot hits the canopy frame, ricochets, fragments embed in the pilot’s shoulder. The pilot cries out, loses concentration for a half second.

Owen fires the third shot. This round enters the open cockpit, travels 28 in, strikes the pilot in the head just behind his right ear. The pilot slumps forward against the control stick. The Zero’s nose drops. The aircraft enters an uncommanded dive. Owen fires his fourth shot at the engine cowling, aiming for the fuel tank.

The round penetrates the thin aluminum, finds nothing critical, exits clean, but it doesn’t matter. The pilot is dead or unconscious, and a zero without a pilot becomes a tombstone with wings. The aircraft spins left, diving steeper, accelerating toward the jungle below. Owen tracks it with his eyes, breathing hard, adrenaline screaming through his veins. The pistol shakes in his hand.

Three rounds remaining. Two zeros still hunting. But the remaining zeros don’t see what happened. They’re engaged with other targets 800 yd away, focused on their gun runs. They don’t see their squadron leaders spiral out of control. They don’t see the impossible kill. The Zero impacts the jungle canopy at approximately 420 mph.

vertical descent 11,000 ft below Owen’s position. The crash creates a fireball visible for three miles. Trees explode outward from the impact point. The fuel ignites, sending black smoke into the morning sky. Owen holsters his pistol. His hand trembles. His breath comes in ragged gasps. The cold air burns his lungs.

The shrapnel wound pulses with pain. He looks around, assessing. Six American parachutes still descending. Two zeros still circling. His odds improved marginally from certain death to merely probable death. The remaining zeros complete their attacks on two more crewmen. First Lieutenant David Parker, the navigator, takes rounds through both lungs, dies choking on blood at 8,000 ft.

Technical Sergeant William Hayes, the engineer, catches a burst through his abdomen, bleeds out during the descent, corpse landing in the jungle 20 minutes later. Five Americans reach the ground alive. Owen lands in Triple Canopy Jungle 3 m from the bombers’s crash site. He releases his parachute harness, collapses against a teak tree, examines his wounds.

The shrapnel tore through muscle, missed the bone, bleeding, but manageable. He fashions a tourniquet from parachute cord, ties it tight, focuses on survival. The Japanese army controls this territory with elements of the 18th Infantry Division. Approximately 12,000 troops spread across 300 square miles. They patrol aggressively.

They take few prisoners. Owen has no radio, no map, no compass. He has his pistol with three rounds, a survival knife, a canteen, and 1200 m of enemy territory between him and safety. He evades capture for 5 days. He travels at night, navigates by stars, avoids villages, drinks from streams, eats nothing.

Malaria fever sets in on day three. The shrapnel wound becomes infected on day four. On day five, a Japanese patrol finds him unconscious beside a water buffalo trail. They transport him to Rangon Central Prison, a facility housing 800 Allied PS in conditions that kill 30% within 6 months. Owen shares a cell with 11 other captured airmen.

Dysentery berry berry malnutrition beatings interrogations. The Japanese want intelligence on bombing tactics, airfield locations, aircraft capabilities. Owen provides name, rank, serial number, nothing else. The guards break his ribs during one interrogation session. They withhold food for 6 days. during another.

They put him in an isolation box 4T x 4tx 3 ft tall for 14 days in tropical heat. He survives by rationing his sanity, counting seconds, doing mathematics in his head, remembering Texas summers and ice cream and everything worth staying alive for. The other survivors from his crew reach the same prison over the following weeks.

The co-pilot dead. The navigator dead. Three enlisted men dead. Five reach Rangon alive. Two die from disease within 3 months. Three survive until liberation. The war continues without them. The Allied advance through Burma accelerates. In 1945, British forces retake Rangon in May. Owen walks out of prison on May 6th, 1945, weighing 93 lbs, down from 165, he requires hospitalization for 7 weeks, treatment for multiple tropical diseases, reconstructive dental work, psychological evaluation.

The debriefing officers take his statement. He tells them about the parachute descent. The zero attack, the pistol shots. They write it down, file the report, mark it unconfirmed, no witnesses, no wreckage recovery, no verification possible. The claim remains officially unrecognized. Owen returns to the United States in July 1945, arrives at Camp Stoman in California, processes through demobilization, receives his discharge papers, takes a train to Texas.

He weighs 120 lb, walks with a limp from the shrapnel wound, startles at loud noises. The army awards him the Purple Heart for wounds received in action. No air medal, no distinguished flying cross, no recognition for the impossible kill. He goes home to Graham. The town holds a parade, welcomes him back, asks about his experiences.

He says very little. What happened in Burma stays locked behind his teeth. He takes a job at his father’s dry goods store, stock shelves, manages inventory, tries to build a normal life. He married in 1947, has three children, coaches little league baseball, and serves on the Graham school board. People know he flew in the war, know he spent time as a prisoner, don’t know the details. He doesn’t tell war stories.

He doesn’t attend veterans reunions. He lives quietly. The confirmation comes in 1982, 38 years after the event. A researcher studying Japanese military records discovers patrol reports from March 31st, 1944. A zero from the 64th Centai fails to return from a mission over Burma. The pilot, Lieutenant Shigoshi Kuro, 11 confirmed victories, considered for promotion.

His squadron mates report he broke formation during an attack on enemy parachutists, pursued a target at low altitude, and failed to rejoin. Search parties found his crashed 03 mi from a downed American bomber. The cockpit showed bullet damage. The pilot died from a small caliber gunshot wound to the head.

Japanese investigators concluded he was shot by ground fire, possibly from Chinese guerillas. But no Chinese forces operated in that area. No ground combat occurred within 10 mi of the crash site. The only small caliber weapons belong to the downed American air crew, specifically their service pistols. The researcher contacts the Air Force Historical Research Agency, provides the Japanese documents, requests correlation with American records.

The search leads to Owen Bagot’s afteraction report filed in 1945 marked unconfirmed. The details match perfectly. The date, the location, the circumstances, the outcome. The Air Force reviews the evidence, consults historians, examines precedent. They find no other verified case of an air crew member shooting down an enemy aircraft with a pistol while parachuting.

Owen Bagot’s claim becomes officially recognized as a confirmed kill, the only one of its kind in military aviation history. Owen receives notification by mail in February 1983. A brief letter from the Secretary of the Air Force. Formal language. Congratulations on the confirmation of his aerial victory. No ceremony, no metal upgrade, just acknowledgement that what happened at 15,000 ft over Burma actually happened.

Documented in both American and Japanese records. A reporter from the Graham Leader newspaper interviews him. Owen describes the incident in factual terms. No embellishment, no drama. He shot a pistol at a zero. The zero crashed. He got lucky. The reporter asks how he felt in that moment. Owen says he felt terrified and certain he would die.

The reporter asks if he’s proud. Owen says he’s proud he survived and came home. The story circulates through aviation history circles, appears in military journals, gets mentioned in documentaries about unusual combat achievements. Owen declines most interview requests. He attended one Air Force reunion in 1985, spoke briefly to a group of bomber veterans, answered questions politely, left early.

Owen Bagot dies on May 26th, 2006 in Graham, Texas, age 85. Natural causes surrounded by family. His obituary in the local paper mentions his military service, his business career, his community involvement, his family. It includes one line about shooting down a Japanese fighter with a pistol while parachuting over Burma.

Most readers assume it’s a mistake or an exaggeration, but it’s not. The Japanese records confirm it. The American records confirm it. The laws of physics barely allowed it, but it happened. Lieutenant Shigoshi Kuro died doing his duty, following orders, executing defenseless men in parachutes.

According to the brutal logic of total war, his death exemplified the random violence that consumed 50 million lives between 1939 and 1945. He was somebody’s son, possibly somebody’s brother, trained by his nation to kill without hesitation. Owen Bagot survived by violating every reasonable assumption about aerial combat.

Pistols don’t shoot down fighter aircraft. Parachuting men don’t win gunfights against zeros. The impossible doesn’t happen, except when it does, witnessed only by dying men and documented decades later by archival researchers. The legacy lives in the records. Air Force training materials reference the incident as an example of survival mindset under impossible circumstances.

The M1911A1 pistol served American forces for 74 years from 1911 to 1985. Chambered for 45 ACP. Designed by John Browning, carried by millions of servicemen. Owen’s pistol, serial number unknown, likely ended up in a Japanese warehouse after his capture, redistributed, lost to history. The zero he shot down, aircraft number unknown, disintegrated in the jungle.

No recovery team retrieved the wreckage. Tropical vegetation consumed it within 5 years. Rain and insects and time erased the evidence, leaving only paper records and filing cabinets on opposite sides of the Pacific. Burma gained independence from Britain in 1948, became Myanmar in 1989. The jungle where Owen landed remains largely unchanged.

Still dense, still dangerous, still indifferent to what happened there. The location coordinates exist in documents, but nobody marks the spot. No memorial, no monument, just trees and time. The other men from Owen’s crew rest in various places. Some in military cemeteries, some in family plots back home, some never recovered. Technical Sergeant Robert Johnston lies buried in Manila American Cemetery, grave reference plot D, row 7, grave 142.

First Lieutenant David Parker rests in Arlington National Cemetery, section 12, site 894. The others scattered across the map, remembered by families, forgotten by history. Owen’s grave sits in Pioneer Cemetery in Graham, Texas. A simple marker with his name, dates, and service branch. No mention of the zero.

No reference to the impossible shot. Visitors walk past without knowing what happened at 15,000 ft on March 31st, 1944. The story survives because researchers care about accuracy. Because Japanese recordke keepers documented losses meticulously. Because one impossible moment produced enough evidence to survive eight decades of skepticism.

Statistics provide context. The Army Air Forces lost approximately 94,000 personnel during World War II. Killed in action, died of wounds or lost in accidents. Approximately 40,000 died in the Pacific and China Burma India theaters. The 10th Air Force Owens unit lost 568 aircraft and approximately 4,000 personnel.

Most deaths left no witnesses, no documentation, no recognition. Owen’s survival defied those odds. His shot defied physics. His confirmation defied the bureaucratic tendency to dismiss extraordinary claims. Three separate impossibilities compounded into one verified fact. If you’re watching till now, then do me a favor. Hit that like button.

Every single person who likes counts to YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re discovering forgotten stories from Dusty Archives every single day. Stories about bomber crews fighting impossible odds over Burma. Fighter pilots defending their comrades.

Ordinary men doing extraordinary things because circumstances demanded it. Real people, real heroism. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a viewer.

You’re part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you’re here. Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure Owen Bagot doesn’t disappear into silence. These men deserve to be remembered, and you’re helping make that

News

Admiral Shibazaki Boasted “It Will Take 100 Years to Capture Tarawa” — US Marines Did It In 76 Hours

At 13:30 hours on November 23rd, 1943, Colonel David Shupe stood on a two-mile strip of coral called Betio,…

Japanese Troops Were Terrified When U.S. Marines Cleared Trenches Without Letting Go Of The Trigger

On the morning of August 17th, 1942, at 0917, Sergeant Clyde Thomasson crouched behind a palm tree on Makan Island,…

Japanese Soldiers Were Terrified When .50 Caliber Machine Guns Penetrated Their Concrete Bunkers

On the morning of May 14th, 1945, at 0630 hours, Corporal Lewis Ha crouched behind a coral outcrop on Okinawa’s…

General Hyakutake Ignored The “No Supplies” Warning — And Marched 3,000 Men Into The Jungle To Die

On the morning of December 23rd, 1942, at 0800 hours, Lieutenant General Harukichi Hiakutake sat in his command bunker on…

Colonel Ichiki Was Told “Wait For Reinforcements You Fool” — He Attacked Anyway And Lost 800 Men

At 3:07 in the morning on August 21st, 1942, Colonel Kona Ichiki crouched behind a fallen palm tree on the…

Japanese Soldiers Were Terrified When U.S. Marines Turned Anti-Tank Guns Into Giant Shotguns

On the morning of August 21st, 1942, at 3:07 a.m., Private First Class Frank Pomroy crouched behind a 37 millimeter…

End of content

No more pages to load